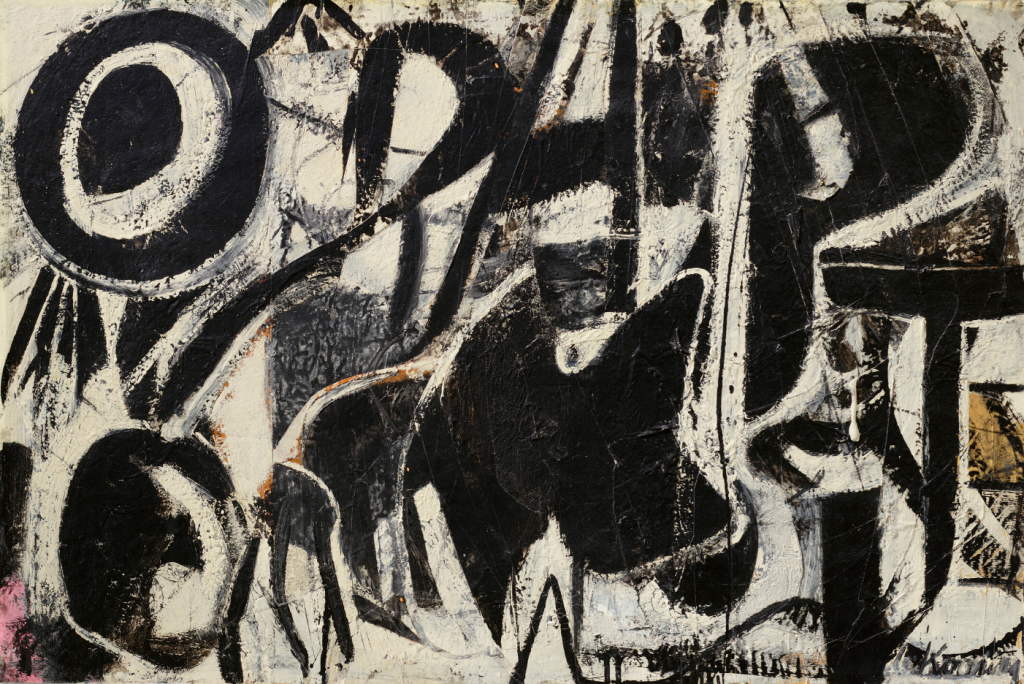

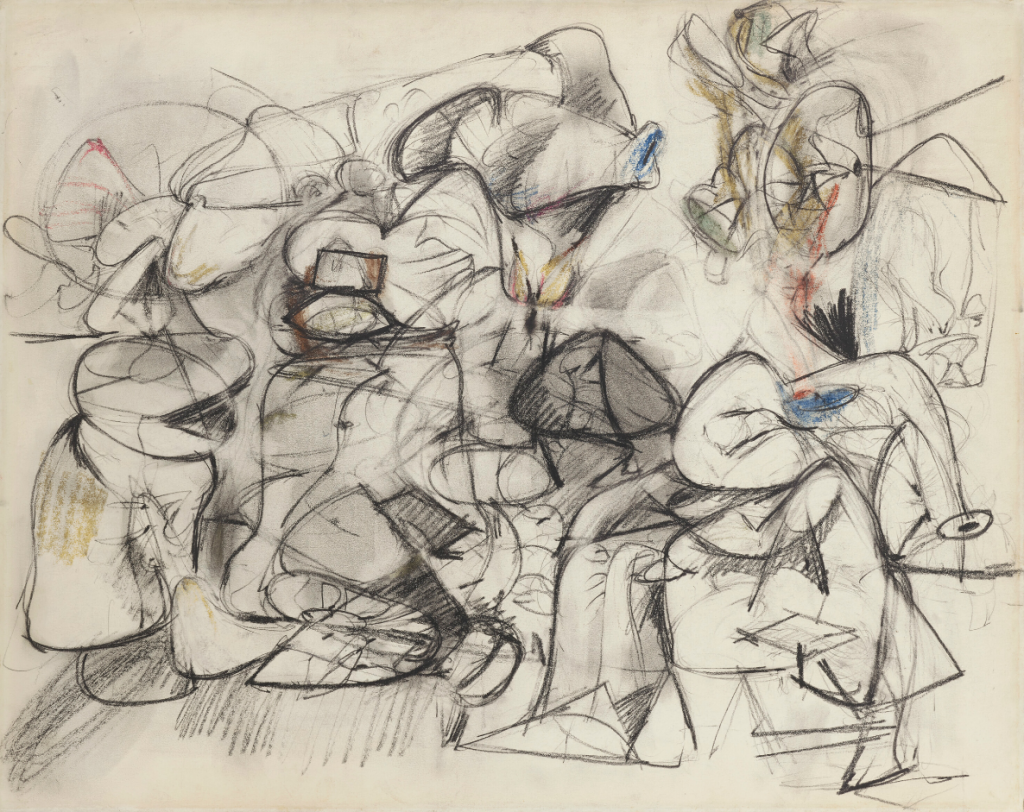

This rare work from the artist’s black and white period provides myriad viewpoints into the origins of his process and style.

Si Newhouse had a knack for collecting work that captured the height of an artist’s unique powers, and Willem de Kooning’s Orestes was no exception.

Last appearing at auction in 2002, it is one of the most important early paintings by de Kooning to remain in private hands, signifying the pivotal moment in his career when he liberated himself from the pure figuration that he had studied in Rotterdam and began cultivating his characteristic blend of lettering, gestural figures and abstract motifs.

Thomas B. Hess described it as ‘a new kind of painting: There are no lines. Neither are there backgrounds, nor foregrounds. The blacks and whites push in front of and slip behind each other… It’s as if two philosophers were having a conversation about Black and White, but everything could only be cited in terms of its opposite.’

Willem de Kooning (1904-1997), Orestes, 1947. Oil, enamel and paper collage on paper mounted on board. 24⅛ × 36⅛ in (61.3 × 91.8 cm). Estimate on request. Offered in Masterpieces from the S.I. Newhouse Collection in May 2023 at Christie’s New York.

The feeling of disorientation, a constant in de Kooning’s action paintings, is a result of his bold merging of abstraction and figuration.

This May, Orestes will be offered as part of Masterpieces from the Collection of S.I. Newhouse, during Christie’s 20th and 21st Century sale week in New York.

Made in 1947 and exhibited as part of the Dutch-American Abstract Expressionist’s first solo show at New York’s Charles Egan Gallery in 1948, the painting is part of de Kooning’s black and white series, which he continued to explore for the next two years.

Emigrating from Rotterdam in 1926, de Kooning travelled to Virginia, Boston, and eventually Hoboken, New Jersey. After working as a house painter there for a year, he settled in New York City in 1927.

The following year de Kooning travelled upstate to visit the art colony in Woodstock, where he met other modernist artists active in the area. Soon after, back in Manhattan, he met the Armenian Arshile Gorky and the Russian John Graham. The two loomed large in de Kooning’s early development, but Gorky especially served as an artistic brother for the Dutchman.

De Kooning and Gorky spent much time together in the 1930s, and de Kooning was deeply inspired by the way Gorky blended figurative and abstract techniques. Gorky was, as de Kooning said, an artist with ‘fantastic instinct,’ and the two maintained a close friendship and artistic kinship that lasted until Gorky’s death in 1948.

Gorky’s Untitled (The Horns of the Landscape), from 1944, also in the Newhouse collection, is a study for his iconic The Horns of the Landscape, now held in the Frances Lehman Loeb Art Center at Vassar College. Like de Kooning, Gorky blends technical draftsmanship with gestural looseness, enhancing it through the automatic and unfettered hand typical of his Surrealist influences.

Arshile Gorky, Untitled (The Horns of the Landscape), 1944. Graphite and wax crayon on paper laid down on canvas. 19 × 24 in (48.3 × 61 cm). Estimate: $500,000-700,000. Offered in Masterpieces from the S.I. Newhouse Collection in May 2023 at Christie’s New York.

The puffed-up shapes in Orestes resemble letters, similar to how Gorky’s shapes in Untitled (The Horns of the Landscape) resemble bodies, but de Kooning was always careful to separate them from their meaning. As John Elderfield, who curated the artist’s 2011 retrospective at the Museum of Modern Art, said: ‘De Kooning is content to compose a painting almost entirely with shapes that resemble letters, providing that the letters do not compose words that refer to objects, and actually that are difficult to read as words at all.’

The work is immediate and without perspective, and as our eye moves across the composition, we see how he built out the forms in zinc white and black enamel before the paint was able to dry. Even the artist’s signature, usually the final mark made on a work, was written while the paint was still wet.

These small details are what make Orestes such an apt representation of de Kooning’s working process. It reflects his first job in America as a housepainter through aspects of layering and the material he uses. The black is Ripolin, an inexpensive enamel use by housepainters. The painting is also a masterful exploration of how he formulated a new kind of abstraction that eschewed strict labels.

‘When an artist wants to change, when he wants to invent,’ Barnett Newman said, ‘he goes to black; it is a way of clearing the table — of getting to new ideas.’ De Kooning himself acknowledged the significance of this period in his artistic development, keeping the two cans of enamel and making sure not to lose track of them even as he moved and changed studios.

Source: Christie’s