As Earth Day approaches, it’s worth remembering that the state of our planet does not affect human beings alone. Here are 12 artworks — all of which have passed through Christie’s salerooms — that celebrate some of the wonderful creatures whose future is in our hands

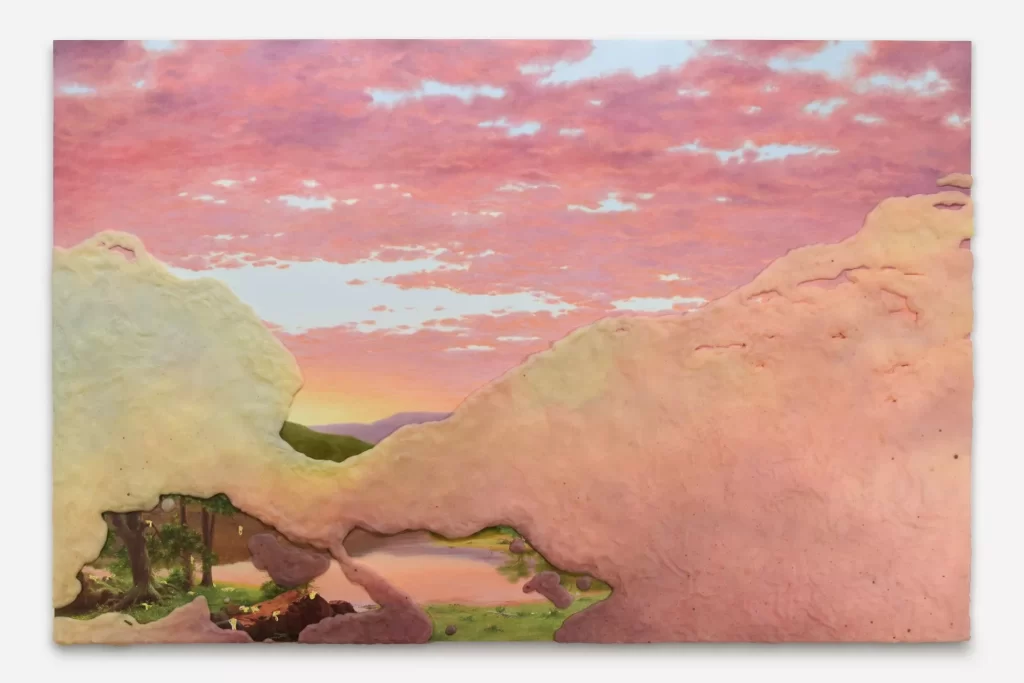

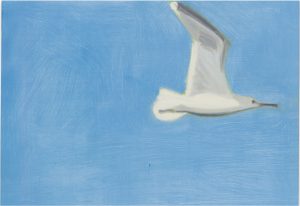

1, Seagull, 1989

While other New York artists of the 1940s and 1950s turned to abstraction, Alex Katz instead championed figuration and the small, everyday moments of his life. Spending his summers in Maine, he pioneered a new visual vocabulary characterised by planes of rich colour, flatly graphic lines and a distinctly Pop aesthetic.

Alex Katz (b. 1927) ‘Seagull’ 1989. Oil on Masonite 30.2 × 40.3 cm

Although he is best known for his portraits of his wife and muse, Ada, Katz has also produced landscapes and paintings of animals, including many of the Katz family dog. Seagull, painted in 1989, highlights the artist’s ability to transform what the critic Sanford Schwartz described as ‘an ordinary moment into the mythic and monumental’. With no clues as to time or place, we are left wondering where this seagull is heading, and why.

2, The Quadrupeds of North America, 1845

The naturalist and artist John James Audubon (1785-1851) made his name with The Birds of America, a thorough study of North America’s bird species. Printed between 1827 and 1838, it contains 435 life-size watercolours, and took 10 years to complete.

In 1843 Audubon, by now aged 58, journeyed across the Rockies to the Great Plains, with the aim of cataloguing the continent’s four-legged beasts. The expedition resulted in The Quadrupeds of North America, the most successful large colour-plate book to be produced in America in the 19th century.

John James Audubon (1785-1851) ‘The Quadrupeds of North America’ 1845. Three volumes, ‘elephant’ broadsheet (685 × 555 mm).

Audubon was particularly fascinated by the larger animals, capturing elk, deer, bears and wolves, among others, in realistic perspective against naturalistic backgrounds.

Many of the smaller mammals, such as these marmots, were executed by his son, John Woodhouse Audubon, as the elder Audubon’s health and eyesight declined. The backgrounds were, for the most part, completed by his youngest son, Victor Gifford, who also oversaw the printing and publication of the book between 1845 and 1848.

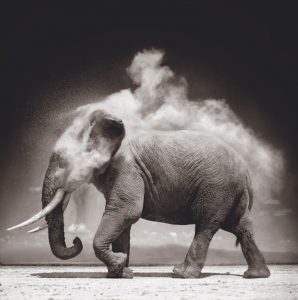

3, Elephant with Exploding Dust, 2004

The Englishman Nick Brandt started photographing animals in East African landscapes more than 20 years ago. Not that the results have been what one might call conventional wildlife photography. Brandt describes his work as portraiture — that is, intimate depictions from close range (he refuses to use a telephoto lens). ‘You wouldn’t shoot a person from 100 feet away… and expect to capture their personality,’ he says.

Nick Brandt (b. 1976), Elephant with Exploding Dust, 2004. Pigment print 96.1 × 96.1 cm

In the case of Elephant with Exploding Dust, Brandt was on the dust-shrouded plains of Kenya’s Amboseli National Park, at around noon one day, ‘when this bull elephant suddenly ambled past’. The resulting image is so artistic, it looks posed — but it was actually just Brandt’s reaction to the beast giving itself a dust bath (an elephant’s way of spraying dirt over its body with its trunk to ward off parasites).

4, The Watchful Doe (‘Biche aux Augets’), c. 1729

In 1725 the French artist Jean-Baptiste Oudry (1686-1755) was invited to the royal kennels of King Louis XV to paint two of his favourite English greyhounds, Misse and Turlu. The 15-year-old monarch attended the sitting and was so impressed by the canine portraits that he employed Oudry to paint his other pointers, setters and hounds — as well as the animals they encountered on their hunts — almost continuously for the next three decades.

Jean-Baptiste Oudry (1686-1755) ‘The Watchful Doe (‘Biche aux Augets’)’ c. 1729. Oil on canvas 182 × 136 cm

This life-size portrait of a doe was created a few years after that royal commission, and highlights Oudry’s brilliant talent as an animalier. The doe is wonderfully alert, ears pricked at a distraction in the distance, while her fur has been skilfully rendered with short, sharp flicks of Oudry’s brush. Shortly before his death, the artist delivered a lecture at the Académie Royale on the techniques required to paint the illusion of fur and feathers.

5, A wood netsuke of a cicada, 19th century

Netsuke — small toggles used to secure pouches to kimonos — originated in 17th-century Japan and often took the form of spiritually important animals and insects, such as rats, monkeys and koi carp. This charming wooden example was carved in the 19th century, during Japan’s Edo period, and resembles a cicada. It’s signed by the artist Harumitsu, who skilfully recreated the bug’s characteristic bulging eyes and the fine membrane of its wings.

A wood netsuke of a cicada. Signed Harumitsu, Edo period (19th century)

Japan is home to some 30 different species of cicada, and the male insect’s noisy mating call, made by expanding and contracting an organ called a tymbal, traditionally represents the arrival of summer. The hotter the day, the louder the high-pitched buzzing it makes.

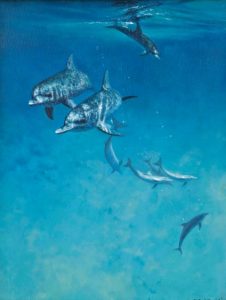

6, Dolphins

The British artist David Shepherd (1930-2017) dreamed of working with animals in Africa, but instead ended up painting the wildlife he wanted to protect. After being rejected as a game warden in Nairobi in the 1950s, he was taken up by the marine artist Robin Goodwin, who agreed to teach Shepherd the basics of oil painting.

David Shepherd (1930-2017) ‘Dolphins’ Oil on canvas 66 × 51 cm

For three years Shepherd learned the value of ‘sticking with it’ and the need to be in the studio seven days a week. The hard graft paid off, and by the 1970s Shepherd’s paintings of elephants, tigers and dolphins had become some of the best-known images of wildlife in the world. The money they made raised millions for Shepherd’s conservation projects, spearheaded by the David Shepherd Wildlife Foundation.

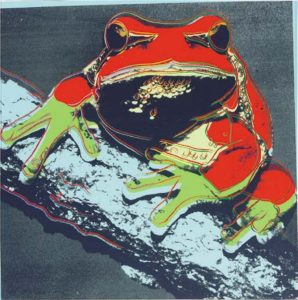

7, Pine Barrens Tree Frog, 1983

In 1983 Andy Warhol made a series of silkscreen prints called ‘Endangered Species’, featuring psychedelically colourful renderings of 10 animals at risk of extinction. These animals included the Siberian tiger, giant panda, black rhinoceros and Pine Barrens tree frog (an amphibian native to the south-eastern United States). The idea was to capture each creature in isolation, so as to convey how few of their respective species survived.

Andy Warhol (1928-1987) ‘Pine Barrens Tree Frog, from Endangered Species’ 1983; 965 × 965 mm

Warhol once flippantly described this series as ‘Animals in Make-up’, because of the unnatural colouring he applied. The 10 subjects are given the same treatment as the likes of Marilyn Monroe and Elizabeth Taylor in silkscreens of previous decades. Warhol’s idea was to confer on the animals the same iconic status that he had accorded to celebrities.

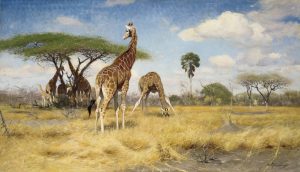

8, Giraffes

This tower of majestic giraffes, complete with their calves, forage for food on the open plains under an intense African sun. The scene was painted by Wilhelm Friederich Kuhnert (1865-1926), a German artist who was encouraged to dedicate himself entirely to animal paintings by his teachers at the Berlin University of the Arts.

Wilhelm Friederich Kuhnert (1865-1926) ‘Giraffes’ Oil on canvas 77.5 × 135.3 cm

Unlike his contemporaries, Kuhnert preferred to study his animals in their native habitats rather than captivity. He visited Egypt, India and East Africa, working quickly in pencil and charcoal to sketch the wild beasts he encountered. He would then return to Berlin and work the studies into oils. In 1903, his images went into wider circulation when they were printed on a series of trading cards issued by Stollwerck, a chocolate manufacturer in Cologne.

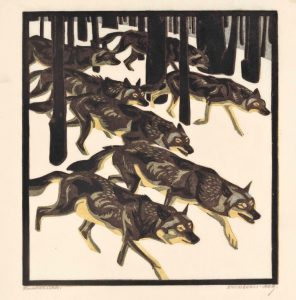

9, Wolves, c. 1920

The pioneering painter and woodcut illustrator Norbertine von Bresslern-Roth (1891-1978) first began making colour prints of animals in the 1920s. She visited zoos in her native Austria and travelled to North Africa so that she might record animals in the wild.

Norbertine Bresslern-Roth (1891-1978) ‘Wolves’ 275 × 248 mm

Born in Graz in 1891, Bresslern-Roth grew up in the shadow of the ecstatic Vienna Secession movement which broke away from the conservative establishment to embrace a modern culture. Influenced by Art Nouveau, Bresslern-Roth’s dynamic Wolves was created in the 1920s and forms part of a series of woodcuts made to illustrate children’s stories.

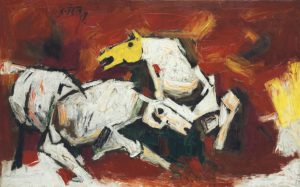

10, Wild Horses

Horses are a recurring theme in the paintings of the Indian artist Maqbool Fidal Husain (1915-2011), who first developed a fascination for the animals as a child while watching effigies of horses paraded through the streets of Lahore on religious holidays.

Maqbool Fida Husain (1915-2011) ‘Wild Horses’ Oil on canvas 76.2 × 121.9 cm

When asked what the horse signified in his paintings, the artist explained that they were ‘multi-dimensional’, having been universally revered since Chinese and Roman antiquity. This dramatic image illustrates Husain’s observation that his horses are ‘like lightning, they cut across many horizons. Seldom are their hooves shown. They hop around the spaces.’

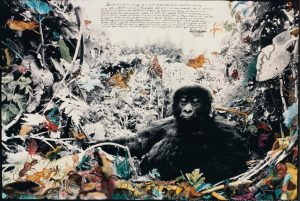

11, One-Year-Old Mountain Gorilla, Rwanda, 1984

For several decades the American photographer Peter Beard (1938-2020) chronicled mankind’s harmful impact on Africa. A habitual traveller to the continent — dating back to his first visit there as a teenager in 1955 — he referred to humans as ‘mismanagers of a diminishing environment’. Beard’s best-known book, The End of the Game, ends with a series of photographs of elephants that have died from starvation.

Peter Beard (1938-2020), ‘One-Year-Old Mountain Gorilla, Rwanda’ 1984; 103.5 × 177.2 cm

One-Year-Old Mountain Gorilla, Rwanda is a 1984 collage featuring a black-and-white photograph of a lone gorilla in the wild, along with multicoloured sketches of fantastical creatures and an excerpt from a treatise by the early Christian writer Tertullian (c.155-c.220). Beard saw remarkable prescience in Tertullian’s words: ‘Surely it is obvious enough, if one looks at the whole world, that it is becoming more fully peopled… Our numbers are burdensome to the world, which can hardly supply us from its natural elements.’

12, Passenger Pigeon

This engraving of two passenger pigeons by Robert Havell is based on a drawing by John James Audubon for his seminal book, The Birds of America.

After John James Audubon (1785-1851) by Robert Havell (1793-1878), ‘Passenger Pigeon (Plate LXII) Columba migratoria Variant 2’ 768 × 629 mm.

It is thought that the passenger pigeon was once the most abundant bird in North America. In 1813, Audubon described a migrating flock in western Kentucky as an ‘eclipse’ that obscured the midday light. Their populations were so vast that they were hunted and trapped indiscriminately, in the belief that no amount of exploitation could diminish their numbers.

By the 1890s, wild flock sizes that had numbered in the millions had been reduced to dozens. On 1 September 1914, the last known passenger pigeon, a 29-year-old female named Martha, died at the Cincinnati Zoo. Mankind had obliterated the species from the face of the Earth.

Source: Christie’s