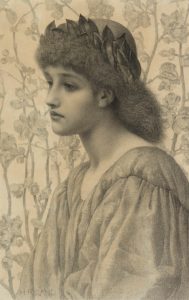

Specialist Sarah Reynolds highlights the sumptuous work of the Pre-Raphaelites’ second and third generations — the successors to Millais, Holman Hunt and Rossetti

They started out as a secret society. So secret that, when they signed their paintings ‘P.R.B.’, a rumour spread that those initials stood for ‘Please Ring the Bell’. They actually stood for the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood: a group of seven artists who held their first meeting in 1848 and wouldn’t remain in the shadows for long.

John Everett Millais, William Holman Hunt, Dante Gabriel Rossetti and their cohorts formed part of what is now deemed the most important British art movement of the 19th century.

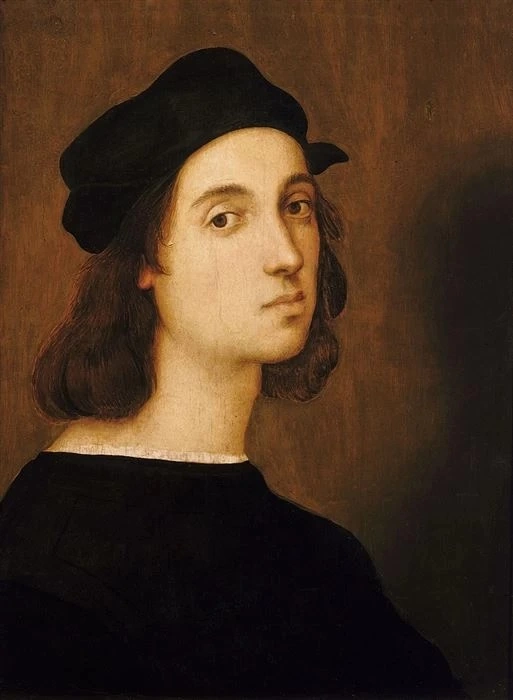

Implicit in their name was a criticism of academic teaching at that time, which treated Raphael and his fellow artists of the High Renaissance as paragons. The Pre-Raphaelites saw earlier Italian painting, of the Quattrocento, as much purer, less mannered and more worthy of emulation.

Millais’s Ophelia (1851-2) and Holman Hunt’s Our English Coasts (1852) are two outstanding examples of Pre-Raphaelite painting — both on permanent view at Tate Britain in London.

John Melhuish Strudwick (British, 1849-1937), ‘When sorrow comes in summer days’

The Brotherhood disbanded within five years, but its ideals were inherited by two succeeding generations. The later Pre-Raphaelites, who worked into the early 20th century, include John Byam Shaw, Evelyn De Morgan and John William Waterhouse.

‘The first generation are the most famous,’ says Sarah Reynolds, specialist in Victorian, Pre-Raphaelite & British Impressionist Art at Christie’s. ‘But the result of that fame is that almost all their paintings are in museum collections and will never come to the market. If you’re looking to buy a Pre-Raphaelite work, many of their successors are much more accessible.’

Several canvases by post-Brotherhood Pre-Raphaelites will be coming to auction at Christie’s in London on 10 December, in The Joe Setton Collection: from Pre-Raphaelites to Last Romantics.

Evelyn de Morgan (British, 1855-1919), ‘Portrait head of a woman, probably a member of the Mure family’

The members of the original Brotherhood shared a fondness for heightened colours, literary and religious subject matter, and meticulous attention to detail all over the canvas. Witness the verdant setting, Shakespearean source and exquisite botanical detail of Millais’s Ophelia.

The second generation formed around Rossetti: its two big names, William Morris and Edward Burne-Jones, both worked with him on the murals of the Oxford Union in the late 1850s.

Burne-Jones would go on to define the movement’s direction in the decades that followed, when it became more decorative and took viewers into a medievalist realm of Arthurian knights and auburn-haired maidens.

Like Morris, Burne-Jones sought to re-enchant a world that he felt had been sullied physically by the Industrial Revolution and morally by the unchecked capitalism of the British Empire. He thought that art’s job, far from capturing modern existence, was to offer an escape from it.

‘I mean, by a picture,’ he said, ‘a beautiful romantic dream of something that never was, never will be.’

Henry Ryland (British 1856-1924), ‘Japonica’

Burne-Jones served as a bridge between the Brotherhood and the third generation of Pre-Raphaelites, all of whose work he influenced to a greater or lesser extent.

In the case of Thomas Matthews Rooke, that influence was direct: he served as Burne-Jones’s studio assistant early in his career.

With 1903’s The Sleeping Beauty, Archibald Wakley responded to a recent Burne-Jones take on the same fairy tale. Blooming, pink flowers surround the princess, who lies on a glittering gold plinth, awaiting the kiss of the prince that will wake her.

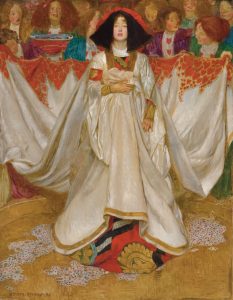

In the case of Byam Shaw’s The Queen of Hearts, it’s the influence of Rossetti that is most keenly felt — in its spatial flatness and the enigmatic, somewhat erotic female subject.

This picture is also indebted to Jan van Eyck’s masterpiece, The Arnolfini Portrait of 1434, particularly in the way the queen clutches the folds of her dress. The van Eyck, which had been bought by the National Gallery in 1843, would inspire several Pre-Raphaelite paintings — something to which a whole exhibition was devoted in 2017-18, Reflections: Van Eyck and the Pre-Raphaelites.

John Byam Liston Shaw (1872-1919), ‘The Queen of Hearts’

‘One of the interesting things about the latter-day Pre-Raphaelites is the number of female artists among them,’ says Reynolds. ‘Where once women had only been muses and models, they now became more active participants.’ These artists included De Morgan, Marie Spartali Stillman, Lucy Madox Brown and Joanna Boyce Wells.

Spartali Stillman was married to an American journalist with an unsettled career. She often had to support him and their six children financially through the sale of her art.

In The Enchanted Garden, she depicts a scene from Boccaccio’s Decameron, where Dianora agrees to visit her admirer Ansaldo only when his garden blooms in mid-winter — which, thanks to a magician in Ansaldo’s pay, has just happened.

A snow-capped landscape can be made out in the distance. However, within the walls of Ansaldo’s garden is a riot of blossom and flowering fruit.

Marie Spartali Stillman (1844-1927), The Enchanted Garden, 1889

In 2019, the National Portrait Gallery in London dedicated an exhibition, Pre-Raphaelite Sisters, to Spartali Stillman and her female peers.

By far the most famous of the third-generation painters is John William Waterhouse, whose The Lady of Shalott is one of the best-known Pre-Raphaelite works. In 2009, he was the subject of a retrospective at the Royal Academy, J.W. Waterhouse: The Modern Pre-Raphaelite.

His renown makes him something of an anomaly among the later Pre-Raphaelites, and he has commanded high prices for many years. In 2000, his painting St. Cecilia sold at Christie’s for £6.6 million, still the record price for a work by the artist at auction.

John William Waterhouse (1849-1917), St Cecilia ‘In a clear walled city on the sea, Near gilded organ pipes… …slept St Cecily’

While we can talk categorically about the first generation of Pre-Raphaelites — given the well-documented membership and lifespan of the Brotherhood — there’s a certain amount of fluidity in what followed.

Some artists might be said to have belonged to both the second and third generations — Simeon Solomon, for example, whom Burne-Jones dubbed ‘the best of us all’.

There was also some crossover between the late Pre-Raphaelites and other movements, such as Symbolism and Aestheticism. Many of De Morgan’s pictures, for instance, are allegories, packed with symbols that the viewer is invited to decipher.

John William Waterhouse (1849-1917), ‘Thánh Cecilia’

Chúng ta có thể bàn về thế hệ tiền Raphael đầu tiên theo sự phân loại có căn cứ, với tên tuổi các thành viên và những năm hoạt động của Hội anh em được ghi chép rõ ràng, thì những gì tiếp theo lại có một số tính lưu động nhất định.

Một số họa sĩ có thể được cho là thuộc cả thế hệ thứ hai và thứ ba, chẳng hạn như Simeon Solomon, người mà Burne-Jones mệnh danh là ‘giỏi nhất trong tất cả chúng ta’.

Cũng có một số giao thoa giữa thời kỳ tiền Raphael về sau và các phong trào khác, chẳng hạn như Chủ nghĩa tượng trưng và Chủ nghĩa duy mỹ. Nhiều bức tranh của De Morgan là những câu chuyện ngụ ngôn, chứa đầy những biểu tượng mà người xem được mời giải mã.

Simeon Solomon (British 1840-1905), Medusa Erotica

The popularity of the Pre-Raphaelites was boosted in 2012 by a major survey exhibition at Tate Britain, Pre-Raphaelites: Victorian Avant-Garde, which later toured to Washington, D.C., Moscow and Tokyo. Reynolds notes that ‘in the 21st century, the movement’s visually striking imagery — with its vibrant colours, pretty patterns and rich fabrics — is proving increasingly popular’.

In 2013, Burne-Jones’s watercolour Love among the Ruins fetched £14.8 million at Christie’s, the highest price ever paid for a Pre-Raphaelite work at auction. As for the third-generation artists, record prices have been set for De Morgan, Byam Shaw and Frank Cadogan Cowper in the past decade.

‘With the exception of Waterhouse, these figures are relatively little-known, so there’s plenty of room for growth in their market,’ says Reynolds. ‘Marie Spartali Stillman’s mastery of detail, for example, matches that of any member of the Brotherhood.

‘One can buy some truly beautiful Pre-Raphaelite paintings at very affordable prices.’

Source: Christie’s