Part 1: Genetics in art

“Biological function” of art

Philosopher Francis Bacon once said: “Art is human adding to nature.” According to Van Gogh, it was the only great definition for the word “art” that he had ever known. Manet also believed that the definition is “absolutely correct”. (And it is correct only when we can answer the question: Do we really understand nature?)

In the 20th century, Mark Rothko raised an interesting concept to supplement previous definitions of art. He called art a “species”: the species of art. Is it true that, on the evolutionary path of all things, the appearance of “the species of art” is a solution of the general equation of the universe? That’s why, after discussing everything related to art, including the supreme thing that he called “summa cum altima”, Rothko still did not forget to remind us: “Art as a natural biological function.”

Somewhere in Vietnamese concept, art is also considered a creature: with appearance and emotions, with specifications and dreams, with birth and death. According to folk songs: “The two of us are like newly painted statues, like newly painted paintings, like newly built pagodas”, or “When we pass by the communal house, we take off our hats to look, the love is as much as the tiles.” Nguyễn Gia Trí said about lacquer material: “Lacquer also has its own life: young, old, and dead.” In “Thăng Long city of nostalgia”, Bà Huyện Thanh Quan wrote a beautiful verse about architecture, about the impermanent beauty of birth and death, as a hint that art is inherent in the overall movement of nature:

The stone is still inert with the years and moons,

Water still frowned with grief.

The “biological function” of art is also recognized in the phenomenon of transmitting “artistic codes” through generations. This transmitting takes place from a biological and cultural perspective, which have a close organic relationship with each other.

Genetic code of art

If we consider the origins thoroughly, all humans have their starting point somewhere in East Africa. Through the process of migration, adaptation to natural conditions, and creation of sociocultural characteristics, ethnic groups with different names and identities are formed. Along with that are the artistic identities of each nation. The concepts of “genetic code of art” and “genetic code of architecture” are proposed from such a perspective.

The genetics of art can be examined through biological base, national psychology, historical data (events, documents, social institutions, religion…), tangible heritage (architecture, sculpture, painting, costumes, fine crafts…), intangible heritage (music, folk songs, proverbs, folk tales…) A mechanism (configuration, principle) of creation which is maintained “long enough” through historical periods by generations of a nation is considered genetic, representing a genetic code of art.

The genetic code of art lies deep within the expressions of culture and art. It silently impacts the creative process without artists and the public easily realizing it. The genetic code passes through different eras, connecting different styles and trends to return everything back to the original characteristics of the nation, and beyond that, the species.

The genetic code of art is established, inherited and adjusted through different eras. There are genetic codes that last throughout the history of founding and development of the nation, but there are also genetic codes that only exist until a certain period and then “disappear” (but still have a hidden influence), because it is no longer suitable for the times.

The Holy Mother of Vladimir (Andrey Rublev, 1495)

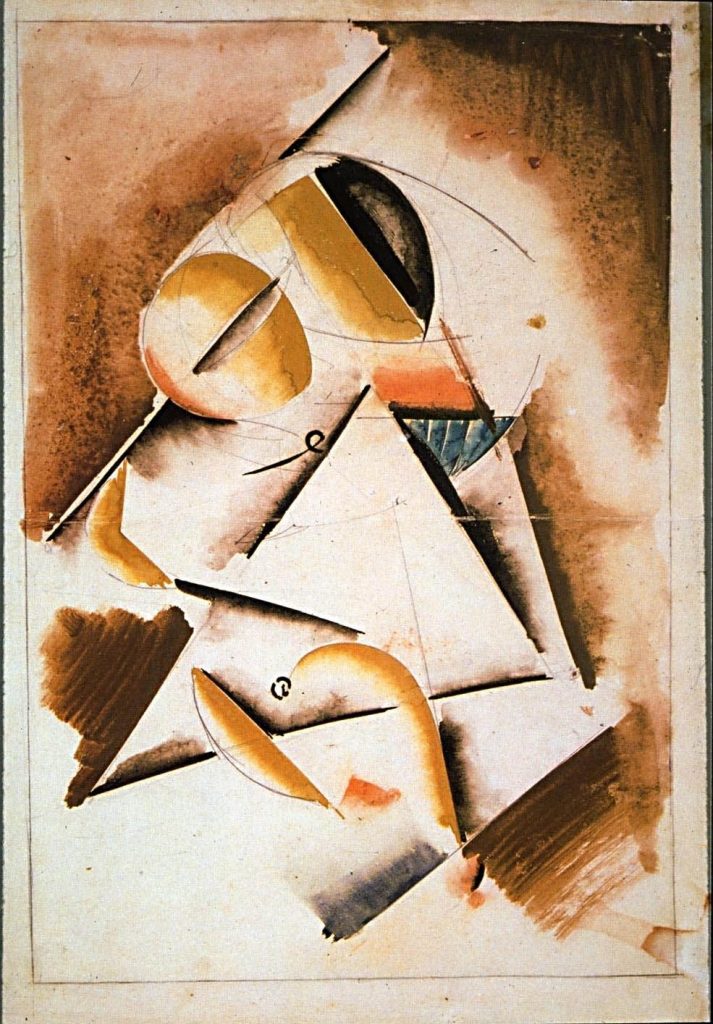

Holy Mother (Vladimir Tatlin, 1913)

The Holy Mother of Petrograd (Kuzma Petrov-Vodkin, 1920).

In the above paintings, even though they were created by different artists, in different political, social contexts, and in different styles, we still recognize a common characteristic of beauty associated with faith (as Dostoevsky said, “beauty saves the world”).

Tatlin, a typical representative of the Pioneer movement, with an aesthetic concept that completely changed from the previous one, still did not forget the traditional Orthodox spirit. And Petrov-Vodkin, one of the first stars of Socialist Realism, painted a worker holding her child while still evoking the image of the Virgin Mary and Jesus in ancient Russian saint paintings.

National character

National psychology (more specifically as national character and national perception) is an important factor in understanding the genetic code of art. It has both biological as well as cultural inheritance.

Have we ever asked the question why Impressionist painting was actually born in France, High-tech architecture started in England, Pop-art appeared and was encouraged in America but not in other countries? Are concepts like Impressionism, High-tech, Pop-art inevitable choices in the history of art or are they just fragments that fit the social context as well as the human mentality of those nations? The freedom and sophistication of the French, the British’s love of science and technology, the Americans’ respect for democracy and media – surely these are valid human/national bases for those movements appear.

A created work of art is not only the story of the individual artist but can also be the loud voice of the community. A work is created by a person, but whether it can live or not depends on society. A stone is known as a gem when it is not underground or in a warehouse, but when it is worn around a woman’s neck at a ball. When art becomes a community issue, the collective psychological element will become an inseparable part of writing, reading and understanding the work. The British’s love of science and technology has contributed to the creation of high-tech architecture, parametric architecture, and vice versa, these architectural styles have strengthened British identity.

Gustave Le Bon wrote: “The character of a nation, not the government, determines its fate.” This statement shows the importance of national psychology to the development of a country, including art. Let’s not praise or blame representative governments as the agents for the rise or fall of the national art scene, but first let’s look for the cause and solution from the perspective of national psychology. When researchers of culture and art during the French colonial period studied An Nam art, they paid great attention to national psychology. For example, Henri Oger wrote about the sloppy quality of Vietnamese painters: “There is no meticulousness and sophistication like Japanese painters to make the product shine. For An Nam people, painting is just like the process of giving an object a coat of varnish.” Clergy Bouillevaux commented on the professional attitude of Vietnamese people: “They start extremely enthusiastic about a job that suits them, they start well in any profession; but after a few months or at most after a few years, they get tired, they hate, neglect their work and often give up their profession, even though they still have to continue working when they are poor.” Paul Giran also commented: “An Nam people only want to do careers that are already outlined, cause them the least unexpected incidents, and require the least creative efforts. That is bureaucracy in the soul. Ambition for power and love of everyday life make them a natural-born official.” Perhaps the perspective of French scholars is one-sided and condescending, but at least they have partly answered the question of why Vietnamese art has not been able to have groundbreaking creations at the heights of the world level.

According to Vũ Dũng, national character “is the enduring psychological characteristics of a nation, formed and expressed in practical activities and communication.” This definition leans toward culturalism, which is also a popular view of Soviet and American scholars, affirming the role of natural, social, and cultural conditions in national character. Even in the United States, the concept of political culture derives directly from studies of national character. Basically, the main idea of culturalism studies in America on the character of nations is to discover the “cultural code” of societies, serving foreign policy, for example in relations with the Soviet Union, Japan, and Việt Nam.

Because national psychology is attched to culture, it can change over time and space. The market economy makes Vietnamese people today more dynamic and focused on personal qualities than in previous centuries, when our ancestors preferred to “bathe in the pond” in the village bamboo or rely on the sound of cooperative gongs. Artists and architects must help themselves to find investment sources and projects, actively participate in competitions and awards at home and abroad to build “brand”. That leads to the situation of making architecture like photography, architects use software to edit photos of buildings to look good then submit them for competitions. In the age of social networks and communications, are people becoming more “virtual”?

Another approach to national character is to use cognition structures, in which there is a special role of the unconscious. The history of a nation’s founding and development, and the way children are raised and educated will greatly impact the psychology of that nation’s adults. For example, G. Gorer analyzed the overall cultural character structure of peoples by placing at the forefront the study of children’s experiences. For Russians, for example, “dressing children in underwear that is too tight, as a severe limitation of the child’s freedom, contributes to an authoritarian attitude in adults and encourages feelings of aggression, disappointed, rivalry. Explaining the contradiction syndrome in Russians: from overactivity to passivity, from isolation to crowd, corresponding to the child putting on and taking off underwear to eat and bath alternately.” The history of Soviet architecture in the 20th century also witnessed a sudden change in creative movements: from avant-garde, leading the vision of world architecture under Lenin, to eclectic, nostalgia, and conservative under Stalin. Then when Khruschev came to power, he moved towards close to the modern West with Brutalism style. Immediately after the dissolution of the Soviet Union, during Eltsin’s time, Russians again favored eclectic forms.

In addition to raising children, myths and folklore are also factors that influence (or reflect) the unconscious in forming national character. For example, B.P. Vysheslagtsev noticed that the Russian character of “reacting to unfairness in an unexpected and spontaneous way” was shown in ancient stories about the heroic men Ilya Muromets or Vaski Buslaev. “Just because he was not invited to Duke Vladimir’s party, Ilya Muromets raised his bow and shot at the cross and the roof of the gilded church. The Russians can suddenly destroy what he considers sacred and has served his whole life just because of temporary anger.” This character has been proven in the most important events of modern Russian history: the October Revolution quickly destroyed social principles that had existed for hundreds of years under the Tsar, churches turned into rubble; And more than 70 years later, the collapse of the Soviet Union also happened suddenly, monuments of Soviet leaders were torn down in the surprise of insiders and outsiders. While the Soviet Union collapsed in an unimaginable way, the socialist state model continued to maintain in China and Việt Nam (although transformed to suit new circumstances). Why so? Perhaps, we need to repeat Le Bon’s saying: “National character determines their fate.” The flexible quality of Vietnamese people has helped our country escape danger in unfavorable situations of the times.

The building of Lloyd (Architect Richard Rogers, 1986)

The building of Gerkin (Architect Norman Foster, 2024).

High-tech architecture was introduced mainly by British architects. That can be explained from the perspective of national psychology: the British are famous for their love of science, and they have convincingly demonstrated the scientific and technological beauty of architecture.

National perception

National perception is the sensory and cognitive characteristics of each nation about the world through the senses, expressed in language and culture. For example, in the modern Eskimo language there are 20 words for the concept of “snow”, while the Aztecs had only one word for both snow, ice, and frost. That’s because Eskimos live in cold climates, so they can distinguish different states of “snow”. Natural, social, and biological environmental factors will impact national perception. Cultural differences also lead to different perceptual concepts, for example, the ancient Romans considered purple a noble color, used in aristocratic clothing, but in ancient China, purple fabric was used for shrouding the dead.

Regarding national genetic factors in music, V.S. Horowitz once said, somewhat pompously, “There are three types of pianists: Jewish pianists, gay pianists, and bad pianists.”

Artistic creativity is based on the perception and actions of the senses, so the role of perception is quite important for national character in art. For example, in European languages, words for colors are very rich, the Vietnamese color of “xanh” spectrum includes different colors that Westerners identify as green, blue, azure, cobalt, marine, emerald, navy, denim, cerulean… (certainly Vietnamese also has names for these colors). Or the purple spectrum in Vietnamese might include the colors purple, mauve, lilac, violet, lavender, magenta, mulberry, iris, periwinkle… In fact, it has also been proven how the colors in European oil paintings are delicate. In the history of Western painting, color theories have been born and colors have been discovered on the palettes of generations of artists. People still cannot fully explain the reasons for the rich color perception of Europeans, but perhaps it is impossible not to mention the alchemical tradition of the Middle Ages and then the development of science (chemistry and optics) in pre-modern times. Perhaps, God gave humans half of their colors in nature, the other half in the laboratory and studio.

Objective reality impact on human psychology is understandable. Just like in Vietnamese, there are a number of typical colors, associated with actual production in Việt Nam such as eel skin color (ceramics), vermilion, cockroach wings (lacquer), scallop color, copper rust, charcoal (woodblock prints)…

While Western artists love and are always looking for materials to create new colors from the East (for example, lazurite (mineral blue) imported from Afghanistan is five times more expensive than gold, or the word “chinese blue” is used for the blue color on Chinese ceramics imported to Europe), East Asian, more specifically Chinese painters were not very interested in exploring color. Is it because the Chinese early structured colors into the five elements (convention of the world of colors into a spectrum of five colors: black, white, yellow, green, red), or they considered colors (in painting) is a mental phenomenon rather than an objective one? Thẩm Tông Khiên wrote: “Everything has shape and color. The pen must create the shape, the ink must evoke the color. But the color here is not blue, red, purple, or yellow, but the color, meaning the density and depth. When used them well, they can express, show the distance, vitality and spirit of the view.”

Traditional Vietnamese art does not develop painting (shapes, colors) but focuses on architectural carving (shapes, blocks). Therefore, the number of words related to Vietnamese wood carving techniques is quite diverse: nông, nổi, bong, kênh, lộng… This corresponds to the fact that “carving” can be considered a genetic code of Vietnamese art. National perception and national character are normal phenomena in psychology and sociology, we need to approach them on a scientific basis, not related to racial or ethnic prejudice.

Climate

Climate is a factor associated with art, especially architecture. Climate is a relatively stable factor (certainly, there is still climate change but that process is slow and long-term compared to generations of architects). Therefore, although social circumstances change and architectural technology develops over time, an architecture in a certain geographical space must always adapt to the same climatic conditions. That makes an important contribution to creating the identity of an architecture as well as creating the unique genetic codes of architecture of each nation. No matter how West Asian and North African architecture changes, they still must ensure the ability to resist heat, dryness, sand and wind, which we can see in the use of brick and stone materials to insulate and moderate windows, in both traditional and modern architecture in these regions.

Basically, Việt Nam is in a hot and humid tropical climate, so architecture must adapt to this condition. That is reflected in traditional components such as “giại” [plate-shaped utensils made of bamboo or wood, placed on the porch to shelter from the sun and wind] (transition of inside/outside space while cooling the inside). Modern architecture uses components with other names such as sunshades, brise-soleils, wind flower walls… but their ecological nature is the same.

In general, the genetic code of art (and genetic code of architecture) are the artistic (architectural) identities that are passed down through generations of a nation due to relative stability in climate and demography, and at the same time built up by cultural layers during migration and settlement, social construction and history.

Written by author Vũ Hiệp