The history of Modern Art is punctuated by moments of rebellion and shock. For that reason, it may surprise many to know that a non-confrontational form of art that was easy on the eyes – painting en plein air (in the open air) – played a key role in the development of early modern art. In Europe, painting outdoors first became popular in the 1830s when a small group French artists packed up their paints and took their easels to the Barbizon forest on the outskirts of Paris. The vibrant canvases of the Barbizon School, fresh and carefully observed, challenged highly finished productions of academic art. Plein air painting trained artists to be alert and responsive to nature, paving the way for the innovations of French Impressionism, a landmark modern style.

In China, where the millennia-old tradition of landscape painting in ink emphasised poetic feeling over observation, Western style plein air painting first appeared after 1910 in conjunction with the New Culture Movement. Practiced alongside life drawing, outdoor painting was seen as an intellectualised and scientific method that strengthened the mind. As more Chinese painters adopted Western oil painting and traveled to rural areas to paint outdoors they were seen as part of a modernist vanguard bringing cultural change. They also worked to loosen rigid rules and literary pretensions of traditional guohua landscape painting.

In France the emergence of plein air painting was aided by the invention of collapsible painting tubes in 1841 which could be stored in special “pochade” supply boxes. This was soon followed by collapsible “French easels”, which could be easily carried. Working in nature, where changes in light and weather forced them to work rapidly and attentively, a new idea of beauty developed. The painter Jean-Baptiste-Camille Corot (1796-1875), a leader of the Barbizon School, once offered that “Beauty in art is truth bathed in an impression received from nature.” This point of view was embraced by the French Impressionists, including Claude Monet (1840-1926) and Pierre-Auguste Renoir (1841-1919), who heightened the impact of their plein air paintings by applying advances in colour theory. The availability of new synthetic pigments, including ultramarine blue and cadmium reds and yellows, brightened their canvases.

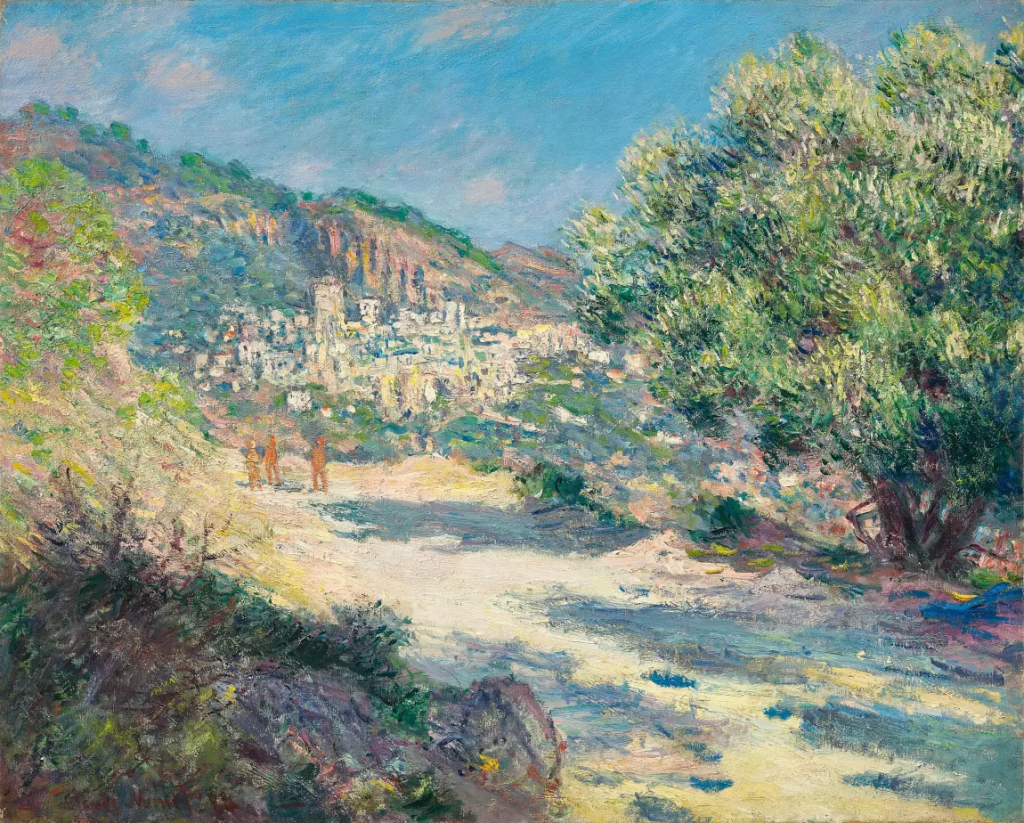

Claude Monet, ‘Route de Monte-Carlo’, 1884

Claude Monet, ‘Inondation à Giverny’, 1886

Monet, who created striking effects of light and shadow by applying complementary colours in short, rapid strokes, was a lifelong advocate of plein air painting. Interested in depicting a particular time of day, he would often paint for less than an hour in one location, and then return at the same time the following day to continue working. The blue-green shadows cast by the trees in Monet’s Route de Monte-Carlo (1883) tell us that the afternoon sun was beginning to move towards the horizon as it lights the faces of buildings in the distance. These direct observations, which a painter working indoors could not have made, endowed Monet’s painting with vivid contrasts of light and colour that engage the eye and heighten the aesthetic pleasure of its viewers. The flickering light in Monet’s Inondation à Giverny, in which the forms of buildings are trees are reflected on floodwaters, demonstrate the artist’s ability to capture rapidly changing weather and momentary effects.

Pierre-Auguste Renoir, ‘Un jardin à Sorrente’, 1881

Renoir’s Un Jardin à Sorrente painted after an 1881 trip to Italy, reflects the impact that painting outdoors had made on the artist’s vision. Like Monet, a close friend who influenced his work, Renoir used small touches of colour to depict his experience of sunlight as it passed through trees or was reflected by water. He had come to understand that rendering light and atmosphere required a different approach. As Renoir wrote to a friend after returning to France: “Thus having seen the outdoors so much, I ended up seeing only the great harmonies without caring any more about small details that extinguish sunlight instead of making it blaze.” By emphasising pictorial harmony over detail, Renoir had discovered the power of depicting atmosphere over detail which is one of the great revelations of plein air painting.

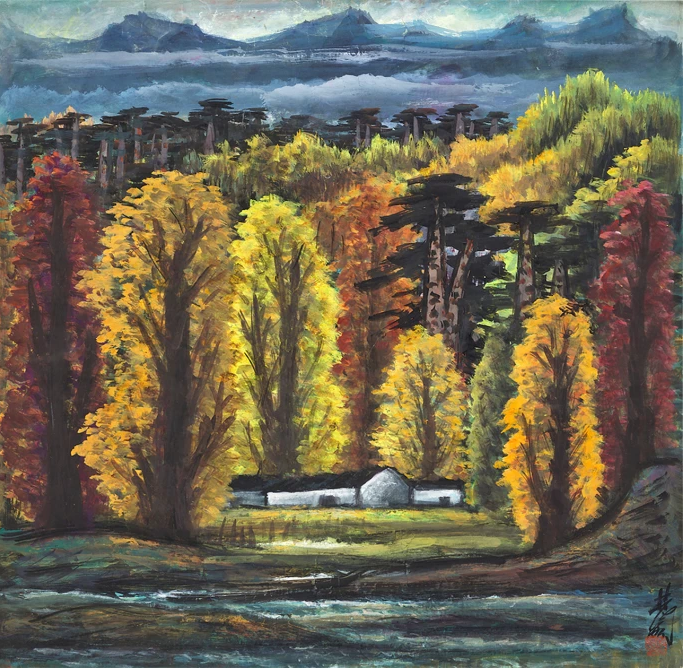

Lin Fengmian, ‘Autumn woods’

Through the end of the 19th century and into the 20th century, European Post-Impressionists including Vincent van Gogh (1853-1890) and Paul Cézanne (1839-1906) – who both worked outdoors – built on the innovations of Impressionism. Their art and the work of other Western modernists was then introduced in China by artists who had travelled overseas including Xu Beihong (1895-1953), who visited Japan in 1917 to study Western art and Lin Fengmian (1900-1991) who left for Paris in 1920 to study at the École nationale supérieure des Beaux-Arts. Upon his return to China, Lin became the director of the National Academy of Art (NAA) in Hangzhou (later known as China Academy of Art), which taught a new generation of students both traditional Chinese painting (guohua) and Western-style painting (xihua).

Wu Guanzhong, ‘Spring over Sichuan mountains’, 1979

Wu Guanzhong, an engineering student who entered the NAA in 1936 against his father’s wishes, would go on to become one of China’s greatest modern landscape painters. In 1947 a national scholarship allowed him to study in Paris for three years where his passion for European modern art—especially the works of Cézanne, van Gogh and Gauguin—changed his ideas about form and colour. Upon returning to China in 1950, Wu taught and traveled throughout China, sketching and painting the scenery he discovered along the way: “In searching for all the marvelous peaks to make sketches, for thirty years during winter, summer, spring, and autumn, I carried on my back the heavy painting equipment and set foot in the river towns, mountain villages, thick forests, and snowy peaks…”

During his long career the subject matter of landscape, which provided an escape from the tensions of politics, was essential to Wu’s sense of expressive freedom: “Whenever I am at an impasse, I turn to natural scenery. In nature I can reveal my true feelings to the mountains and rivers: my depth of feelings toward the motherland and my love toward my people.”

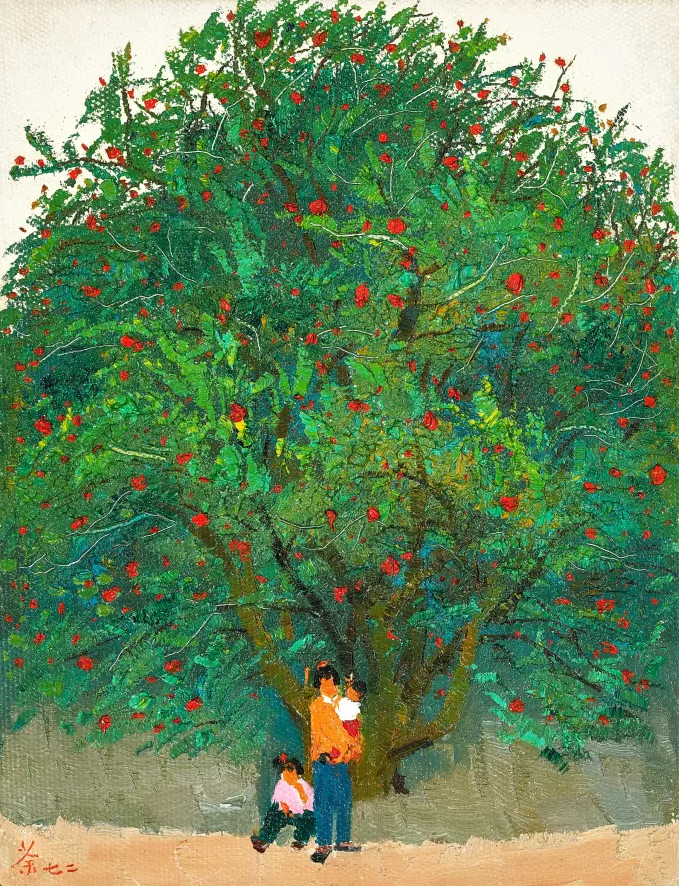

Wu Guanzhong, ‘A tree in the Li village (I)’, 1972

Other notable artists of Wu Guanzhong’s era sought freedom and inspiration by painting outdoors. Fu Baoshi (1904-1965) who lived in isolation in a tiny cabin at the foot of a mountain during the years of war and revolution, often painted outdoors, fortified by wine. After the war a new generation of Chinese artists painted outdoors – sometimes aided by Japanese watercolour techniques and photography – and developed specialised terminology including quijing (view-taking) goutu (composition) and toushi (perspective).

Lê Phổ, ‘Les tulipes oranges’

Throughout the first half of the 20th century travel and colonisation further popularised plein air painting in Asia. In Vietnam plein air painting was taught by French artists to Vietnamese students at the École des Beaux-Arts de l’Indochine, established in 1924. Its numerous graduates, including the artist Le Pho (1907-2001), became adept at rendering scenery, foliage and outdoor light. The dual legacies of plein air painting and French Impressionism are readily apparent in Le Pho’s mature paintings, especially in his floral paintings and in the many scenes he made of elegant women presented in garden settings.

When Abstract Expressionism appeared after World War II, the energetic drip paintings of Jackson Pollock were seen by many as strange and hard to understand. But when Pollock famously explained, “I don’t paint nature, I am nature,” he was expressing something that Chinese artists of the past would have instantly understood: that there is a qi (energy) that runs through all living beings and organisms. The late landscape paintings of Wu Guanzhong, which combined abstraction and representation, were acknowledgments of this flow of energy. In the period following World War II, when many Chinese artists encountered modern art while living overseas, they instinctively embraced abstract painting, building a bridge towards Western abstraction as their work unfolded.

Chu Teh-Chun, ‘Le poids du devenir’, 2005

This is seen in the works of Zao Wou-Ki (1920-2013) and Chu Teh-Chun (1920-2014), where a rich cultural fusion was achieved. Both artists, who were close friends, had their first encounters with Western art while studying at the China Academy of Art in Hangzhou (the former National Art Academy) and both later lived and worked in Paris where the presence of Western art and methods affected their work. In their abstract canvases the vitality of Impressionist painting – which grew out of plein air painting – prevails, infusing their paintings with light, colour and motion. The direct experience of nature, which plein air painting brought to modern art, had become one of the shared inspirations of advanced abstraction in both the East and the West.