Self Portrait with Chinese Lantern Plant (1912) by Egon Schiele. The Austrian artist painted many self portraits during his short life. Courtesy Tokyo metropolitan museum of art.

EGON SCHIELE: YOUNG GENIUS IN VIENNA 1900, TOKYO METROPOLITAN MUSEUM OF ART, 26 JANUARY- 9 APRIL

Young, troubled and talented: Egon Schiele was the doomed rockstar of fin-de-siecle Vienna. Like many of his generation he died tragically young—killed by Spanish flu at the age of 28, just three days after his pregnant wife. And he too left behind an extraordinarily intense body of work.

The exhibition—drawn from the collection of Vienna’s Leopold Museum—will include Schiele’s early mannered studies, produced as a teenager,

as well as his renowned self-portraits, here presented as explorations of a young artist’s identity. Attention will also be given to his haunting paintings of mothers with children, made as the artist was entering artistic maturity, as well as his knotty and erotic nudes and blocky landscape scenes.

This is the first major retrospective of Egon Schiele’s work to open in Japan in nearly 30 years. Alongside more than 50 of his drawings and paintings, it also includes over a hundred works by other artists in and around his adopted home city of Vienna, including Gustav Klimt, Richard Gerstl and Oskar Kokoschka, exploring how his intimate style was influenced by the broader artistic ideas circulating through the Austrian city.

Johannes Vermeer’s The Milkmaid, (1658-59). The show will include 28 of his paintings, the most ever seen together at one time. Courtesy National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC.

VERMEER, RIJKSMUSEUM, AMSTERDAM, 10 FEBRUARY- 4 JUNE

The Rijksmuseum’s achievement in securing 28 of Johannes Vermeer’s 37 paintings has been well publicised, but how will the Amsterdam exhibition actually be presented? The works are to be spaciously spread over ten rooms, with no other art—although inevitably there will be crowds around what are mainly small pictures.

The hang is to be roughly chronological, from Vermeer’s early paintings of the mid-1650s up until his late works completed shortly before his death in 1675. But the strict chronology will be broken up occasionally, to emphasise themes or the artist’s ambitions.

Gregor Weber, the exhibition’s co-curator, intends to put an emphasis on “the play of introvert and extrovert depictions” of characters in the paintings. In some pictures Vermeer subtly suggests interactions with other people outside the paintings by introducing “windows, letters, invitations to play music”, but other compositions focus on meditative figures who are contemplating “in isolation”.

The last major Vermeer retrospective was in 1995-96, in Washington, DC, and The Hague, so the coming Amsterdam show will present his art to a new generation. During the intervening years there has been considerable technical research on the paintings—and we now know much more about how they were made (this material will mainly be presented in the catalogue, rather than in the show).

But a measure of mystery still surrounds these exquisite pictures. As Weber enticingly suggests, we should enter the exhibition to “come closer to Vermeer and experience his secrets”.

Visitors who want to learn more about the artist should also head to Delft (around 50km away) to see Vermeer’s home town. Its municipal museum, the Prinsenhof, will be presenting a contextual show, Vermeer’s Delft (10 February-4 June).

Hokusai’s Yoshitsune’s Horse-washing Falls at Yoshino in Yamato Province (around 1832) © Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

HOKUSAI: INSPIRATION AND INFLUENCE, MUSEUM OF FINE ARTS, BOSTON, 26 MARCH- 16 JULY

Hokusai (1760-1849) has been admired internationally for well over a century, and Boston’s Museum of Fine Arts, with its outstanding Japanese collection, is well placed to present his work in context. The show comprises more than 90 works by the master and over 200 by his contemporaries and worldwide followers.

The first half of the exhibition will trace Hokusai’s relationship with his teacher Katsukawa Shunshō and his links with other Japanese artists and writers of the period. It will also go on to look at Hokusai’s influence on late-19th century European admirers, primarily the Post-Impressionists.

The show’s second half will focus on the 20th and 21st centuries, telling the story of how Hokusai became by far the most famous Japanese artist outside his own country. Appropriately, a room in the centre of the show will be devoted to his famous woodblock print The Great Wave.

Among the exhibition’s surprises will be one of Hokusai’s waterfall prints alongside a 1925 watercolour by the American artist Loïs Mailou Jones. Then aged 20, she was inspired by the Hokusai work to create her watercolour design for a fabric (although it never seems to have been put into production). Jones (1905-98) went on to become a leading member of New York’s Harlem Renaissance group.

The exhibition is likely to travel, although details have yet to be finalised.

Dante Gabriel Rossetti’s Paolo and Francesca da Rimini (1855) © Tate

THE ROSSETTIS, TATE BRITAIN, LONDON, 6 APRIL- 24 SEPTEMBER

The glowing visions of Dante Gabriel Rossetti and his Pre-Raphaelite brethren are familiar enough to art gallery visitors across the UK, and elsewhere; their fraught emotional lives even made it on to mainstream television in the 2009 BBC series Desperate Romantics. Tate Britain’s forthcoming exhibition—perhaps unconsciously—picks up where the TV show leaves off, putting its focus on the Rossettis as a family, and their convoluted entanglements with the likes of Jane and William Morris, for the first time.

Around 90 works by Dante Gabriel Rossetti will go on show in the artist’s first ever retrospective at the Tate, which already holds many of his most famous paintings, including The Annunciation (1849-50), Beata Beatrix (1864-70) and Proserpine (1874). The latter is due to be reunited with The Blessed Damozel (1879) and Mnemosyne (1881) in a recreation of the triptych of “stunners” put together in the drawing room of Rossetti’s early collector, Frederick Leyland. Dante’s sister Christina—the celebrated writer of Goblin Market and In the Bleak Midwinter, as well as the model for The Annunciation—will be represented by recordings of her poetry, while another sibling, William, wrote the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood’s original manifesto.

But the Tate’s real coup is the first full showing of the decade’s worth of work by Elizabeth Siddal, famously the model for John Everett Millais’s Ophelia (1851-52) and a subsequent string of paintings by Dante Gabriel Rossetti, whom she was eventually to marry. Siddal began painting in the 1850s and, sponsored by the critic John Ruskin, worked steadily before her death in 1862. Siddal’s oeuvre is slim—around 30 works—but will be fascinating to see all together.

Hallazgo (Discovery) (1956) by Spanish artist Remedios Varo (1908-63), who lived in exile in post-war Mexico with fellow European Surrealists. Courtesy Art Institute of Chicago.

REMEDIOS VARO: SCIENCE FICTIONS, ART INSTITUTE OF CHICAGO, 29 JULY- 27 NOVEMBER

Remedios Varo and her friends, the British painter Leonora Carrington and the Hungarian photographer Kati Horna, were known as the “three witches”. Part of the circle of exiled European Surrealists in post-war Mexico, they shared a fascination with alchemy and the occult. Varo’s otherworldly paintings are populated by wraith-like figures engaged in mysterious rituals and investigations: a juggler of stars, a scholar threading crystals on an abacus or an explorer charting a course through a river that surges from a single cup.

Working in a virtuosic style that testified to years of academic training in her native Spain and the deep influence of Hieronymus Bosch, she sometimes spent months crafting a single image. When she died suddenly in 1963, Surrealism’s founder André Breton described her as “the sorceress who left too soon”.

Though Varo achieved recognition during her lifetime, her reputation has soared in recent years amid the wider rediscovery of women Surrealists. This summer, around 25 paintings from the height of her career in the 1950s and early 60s, plus drawings and archival materials, will be reunited at the Art Institute of Chicago in the first US solo show dedicated to the artist since 2000, organised in partnership with the Museo de Arte Moderno in Mexico City. Titled Science Fictions, the show seeks to illuminate the tension between modern science and mysticism in Varo’s imagination as well as the “combination of precise planning and chance operations” that informed her meticulous technique.

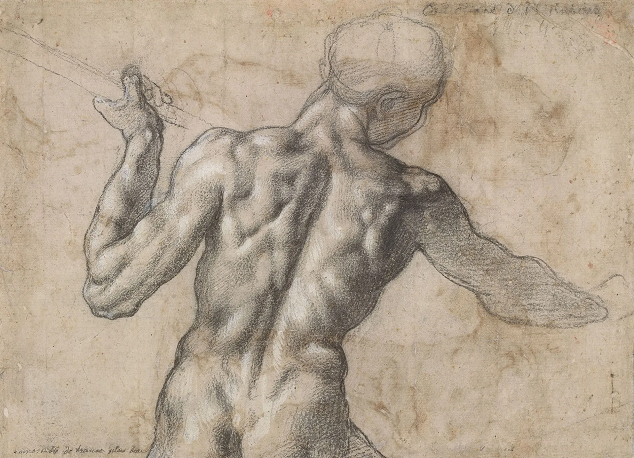

Michelangelo’s Male Nude from Behind (Study for the Battle of Cascina) (around 1504) is one of the show’s centrepiece drawings © The Albertina Museum, Vienna

MICHELANGELO AND THE CONSEQUENCES, ALBERTINA, VIENNA, 15 SEPTEMBER- 7 JANUARY 2024

Once every decade or so, Vienna’s Albertina Museum puts its celebrated collection of Michelangelo drawings on public view. This September, nine of the 13 drawings will serve as the centrepiece of a show on the great Renaissance master in its main exhibition hall. Featuring around 170 works, Michelangelo and the Consequences tracks the artist’s influence on draftsmanship and ideas about beauty across half a millennium.

Works such as Michelangelo’s seated young male nude and two studies of arms (1510 – 1511), with its massive twisting torso, will evoke comparisons with male nudes by artists including Dutch Mannerist Hendrick Goltzius, represented by his oversize 1589 engraving Hercules.

The Albertina draws on its world-class holdings of Old Master drawings and prints to consider Michelangelo’s immense impact in both the 16th and 17th centuries, and the curators have included a number of key drawings by Raphael, Rubens and Dürer. Picking up the thread closer to our own time, Modernist master Egon Schiele, in his brutal 1910 colour drawing Grimacing Nude (Self-Portrait), is a potent reminder of what was gained, and lost, when artists set aside forever the idealised anatomy of works such as Michelangelo’s 1503 depiction of a standing male nude, whose back, buttocks and thighs seem to belong to a statue come to life. Once a part of Rubens’s own collection, the drawing bears the traces of the Antwerp artist’s hand.

The show also features one of Michelangelo’s rare graphic works accurately depicting the female body, Studies of a Seated Female Nude (around 1530-36), which the curators complement with female nudes by Rembrandt, Dürer and Michelangelo’s German contemporary, Hans Baldung Grien.

El Greco’s Sagrada familia con Santa Isabel y San Juanito (around 1585-90), will go on show at the Palazzo Reale. Courtesy of Museo de Santa Cruz, Toledo.

EL GRECO IN THE LABYRINTH, PALAZZO REALE, MILAN, 13 OCTOBER- 9 FEBRUARY 2024

El Greco forged his dramatic style in a number of Mediterranean cities. In Venice, he learned from Titian and Tintoretto how to bathe dark sceneries in brilliant light. In Rome, he analysed ancient statues, as well as Michelangelo’s painting technique. But it was in Toledo, Spain—where he eventually settled—that the Cretan artist produced his best works. Applying what he had learned in Italy, he paved the way for the Spanish School and, some argue, inspired exponents of Expressionism and Cubism centuries later.

Doménikos Theotokópoulos (1541-1614), as he was formally known, will be the subject of a major exhibition at Milan’s Palazzo Reale. The first significant El Greco show in the Italian city for nearly 30 years, it attempts to assess the artist’s development from the perspective of the cities where he was trained and worked. Displays will feature some of El Greco’s best known paintings—including Christ as Saviour (around 1610), Saint Martin and the Beggar (around 1597-99) and Laocoön (around 1610-14)—with loans from the El Greco Museum in Toledo, the Museo Nacional del Prado in Madrid, the Uffizi Galleries in Florence and the National Gallery of Art in Washington, DC, among others.

Juan Antonio García Castro, the director of the El Greco Museum and curator of the Milan exhibition, says that seeing El Greco’s works alongside those of other artists will provide special insights. “Rather than the usual linear or chronological layout, this exhibition has been conceived thematically,” he says. “Our objective is to show what influence El Greco’s contemporaries had on his transformation from a painter of Byzantine icons to a universally recognised artistic genius.”

A “highly individual and energetic interpretation of ancient traditions”: Emily Kame Kngwarreye’s Untitled (awelye) (1994). The Anmatyerre artist (1910-96) was born and raised in Alhalkere in Australia’s Northern Territory. National Gallery of Australia, Kamberri/Canberra © Emily Kame Kngwarreye/Copyright Agency.

EMILY KAME KNGWARREYE, NATIONAL GALLERY OF AUSTRALIA, CANBERRA, 2 DECEMBER- 28 APRIL 2024

Emily Kame Kngwarreye began painting in earnest at around the age of 78 and produced more than 3,000 pieces before her death seven years later—an average of one a day. The Anmatyerre artist was born and raised in Alhalkere, north of Alice Springs in Australia’s Northern Territory, and her work responded to the patterns and textures of the landscape. Stand in front of the brightly coloured canvases and you will notice seeds, waterways and plants amid the repeated lines and dots.

A major new show at the National Gallery of Australia will ground Kngwarreye’s work in the local context. The exhibition brings together canvases from across the artist’s short but remarkably creative career, among them the vast and exuberant Ntange Dreaming (1989), an abstract impression of her country after rain, and Yam Awely (1995), one of her last great paintings. Also on display will be The Alhalkere Suite (1993), a sequence of 22 canvases that celebrates the natural and spiritual forces that nourish the earth. An explosion of pink, turquoise, cherry red and blue, it alludes to the arrival of wildflowers after drought.

Her work is a “highly individual and energetic interpretation of ancient traditions,” says Kelli Cole, who is co-curating the exhibition with Hetti Perkins. While there have been several solo shows of Kngwarreye’s work, this one will benefit from having First Nations curators from central Australia with personal relationships to the artist’s family and cultural connections with her surroundings. “We’ve been working in collaboration with the family and community of Utopia and the Urapuntja homelands to offer a new perspective,” Cole says.

Source: The Art Newspaper