Francis Picabia in his Paris studio on the avenue Charles Floquet, 1912. Photo: © Granger / Bridgeman Images. Artwork: © ADAGP, Paris and DACS, London 2022

The restless Frenchman helped to establish some of the 20th century’s most important art movements — and, typically, quickly moved on in his ceaseless search for the new

One day in 1909 — or perhaps 1908 — the Parisian son of a Cuban diplomat, Francis Picabia, stood in front of a small, blank piece of cardboard, 45 by 61 centimetres in size. The artist had spent the past five years painting Impressionist scenes of Paris’s rooftops and riverbanks, with relative success. But that day, he decided to do something different.

Putting brush to paper, applying rapid hatches of colour and a few sweeping black curves, he marked out a series of seemingly random, muddy-coloured blocks, stacked one on top of the other.

The result — Caoutchouc, now held at the Pompidou Centre — was momentous: Picabia had created what is widely regarded as the first abstract painting in the story of Western art, some four years or more before Wassily Kandinksy would more famously break free from conventional forms.

The end of the line for representational art

Abstraction had existed in Picabia’s mind since childhood, long before he was able to find a way to express it visually. When he was a boy, his grandfather urged him to give up painting in favour of photography. ‘You can photograph a landscape, but not the forms which I have in my head,’ he responded.

Francis Picabia (1879-1953) ‘Jeune fille’ 1912. Oil on canvas. 39⅜ × 31⅞ in (100 × 81 cm). Sold for £504,000 on 1 March 2022 at Christie’s in London

By 1907, despite a successful show of his landscapes, Picabia was clearly still struggling to find a style that matched his vision. He declared that an artist ‘must express the emotion which nature made him feel without the least care for technique’. In order to reach his goal, he said, he would need to break entirely from pictorial conventions by painting ‘pure inventions which recreate the world of forms according to its own will and its own imagination’.

Even after creating that small watercolour in 1909, he was still unsure about its intentions. It took him several years to settle on naming it Caoutchouc, which translates as ‘rubber’. It was inspired by Raymond Roussel’s book Impressions d’Afrique, which centres on a decaying rubber tree that signals the end of an emperor’s lineage. Picabia, retroactively, was declaring Caoutchouc the end of the line for representational art.

Constant reinvention

Yet Caoutchouc was not to be Picabia’s sole legacy. Instead, his endowment to art was an entire career characterised by constant reinvention. As his friend Marcel Duchamp once said, his oeuvre was a ‘a kaleidoscopic series of art experiences’.

Francis Picabia (1879-1953) ‘Geai bleu’ 1938-1939. Oil on board. 41⅝ × 32 in (105.6 × 81 cm). Sold for £327,600 on 1 March 2022 at Christie’s in London

Picabia was born in 1879 in Paris. His father’s fortunes afforded the family a life of comfort, but not without tragedy: when Picabia was seven, his mother — a Frenchwoman, Marie Cécile Davanne — died from tuberculosis.

As a boy, Picabia would copy his grandfather’s paintings, before swapping them and selling the originals. ‘When no one noticed, I discovered my vocation,’ he said.

After studying at the Ecole des Arts Décoratifs in Paris under the history painter Fernand Cormon, he became an Impressionist, merging the styles of Monet, Pissarro and Sisley. Some critics called him a ‘master landscapist’, but while his contemporaries painted en plein air, Picabia copied his pictures from postcards, leading others to say they lacked sincerity.

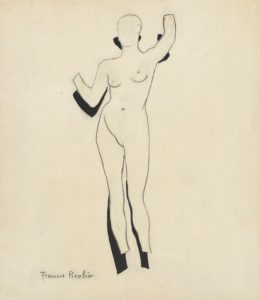

Francis Picabia (1879-1953) ‘Nu debout’ circa 1924-1928. Paper collage, brush and ink and pencil on paper. 14⅛ × 12⅜ in (35.7 × 31.5 cm). Sold for £32,760 on 4 March 2022 at Christie’s in London

Fauvism, Cubism and Dada

After a brief period of experimenting with Fauvism, using Matisse’s rich palette to paint the French coast and still lifes, he transitioned to Cubism. In 1911, along with Duchamp, Robert Delaunay and Fernand Léger, he became associated with Section d’Or, a collective with a common interest in geometric painting. The outbreak of the First World War, however, brought an end to their activities.

Picabia made several trips to New York between 1913 and 1915. There, he renounced Cubism and — along with Duchamp and Man Ray — developed the nihilistic art movement Dada, which rejected logic and reason in reaction to the atrocities of war. He found success with his Portraits Mécaniques, in which bodies morphed into pistons and pumps, exhibiting them at Alfred Stieglitz’s gallery 291; he also contributed to the journal of the same name.

By 1916, however, Picabia was back in Europe, first in Barcelona, then Paris and Zurich, where he sought treatment for addiction (to alcohol and opium) and suicidal thoughts.

Surrealism, Satie, and pasta on canvas

Five years on, Picabia denounced Dada, turning his focus to the new movement of Surrealism. He appeared in René Clair’s 1924 Surrealist film Entr’acte, firing a cannon from a rooftop — a scene that also served as an intermission for Picabia’s Surrealist ballet Relâche, with music by Erik Satie.

Francis Picabia (1879-1953) ‘Tête de faune’ 1934-1935. Oil on canvas. 21⅞ × 18⅛ in (55.5 × 46 cm). Sold for £81,900 on 1 March 2022 at Christie’s in London

Throughout the 1920s and 1930s, Picabia’s style appeared to change almost daily as he hopped between abstraction, figuration and optical illusion. He also experimented with using household paint, feathers and pasta on his canvases. Lampe, painted in Paris around 1923, during the final ‘anti-Dadaist’ phase of his anti-art Paris-Dada period, sold at Christie’s London in 2016 for £3,637,000.

Constant innovation was the thread that connected his output. The American writer and collector Gertrude Stein said that ‘although he has in a sense not a painter’s gift, he has an idea that has been and will be of immense value to all time’.

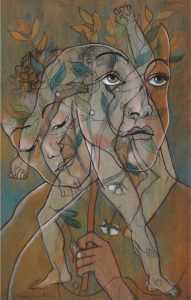

The ‘Transparence’ series

One of his most celebrated inventions was the hallucinatory ‘Transparence’ series. Reminiscent of multi-exposure photography, the pictures superimposed portraits lifted from the Renaissance onto Catalan frescos in a bid to push figuration to new heights.

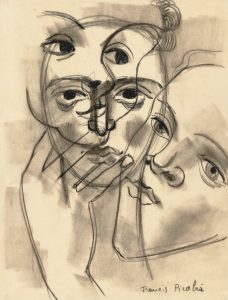

Francis Picabia (1879-1953) ‘Sans titre’ circa 1929-1931. Charcoal and crayon on paper. 12¾ × 10¼ in (32.5 × 26 cm). Sold for £50,400 on 4 March 2022 at Christie’s in London

The series began in the late 1920s while the artist was living in the south of France, and was interpreted as a critique of the frivolous lifestyles of the inhabitants of the Côte d’Azur. Picabia’s response was to explain that the images were expressions of his ‘inner desire’, which only he was able to decode. Their commercial success, however, afforded him his own hedonistic existence of lavish parties, gambling, cars and yachts.

Francis Picabia (1879-1953) ‘Ligustri’ 1929. Oil, gouache and brush and black ink over pencil on panel. 59¾ × 37⅞ in (151.5 × 96.2 cm). Sold for £3,491,250 on 5 February 2020 at Christie’s in London. Artwork: © ADAGP, Paris and DACS, London 2022

Nude portraits

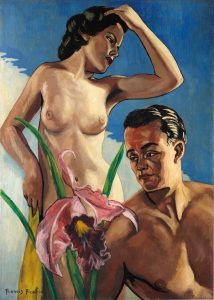

In 1937, Picabia’s work took yet another surprising turn. The artist started to produce realistic nude portraits, lifting subjects from soft-core pornographic magazines and adopting smooth, fluid brushwork to mimic the sheen of photographic paper.

Initially, their aesthetic drew comparisons with that of Third Reich propaganda, but scholars today regard these paintings as forerunners to the subversion of mass media seen in the work of Rauschenberg, Warhol and Koons.

Francis Picabia (1879-1953) ‘Adam et Eve’ 1941-1942. Oil on board. 41½ × 29⅝ in (105.5 × 75.3 cm). Sold for $3,367,500 on 17 May 2017 at Christie’s in New York. Artwork: © ADAGP, Paris and DACS, London 2022

Picabia’s final years were plagued with ill health, yet he worked tirelessly, cherrypicking from the disciplines he had helped shape to create hybrid works that simultaneously merged and defied Surrealism, abstraction and figuration.

In the spring of 1949, to mark Picabia’s 70th birthday, the Galerie René Drouin in Paris mounted a retrospective featuring 136 works that spanned his entire career. The catalogue, designed to look like a newspaper, contained articles and poems by his friends, among them André Breton and Jean Cocteau, printed in different directions across the page.

Four years later, Picabia died. He was interred in Montmartre Cemetery.

During his lifetime, Picabia’s work was often misunderstood, perhaps because of its fleeting nature, existing between the lines of the movements that he played such a pivotal role in creating. Today, he is remembered for his anarchic spirit and disregard for convention.

As a critic writing in 1928 expressed it, ‘Picabia is the grasshopper of contemporary art, leaping lightly from ism to ism and having a very gay time of it.’

Source: Christie’s