David Hockney’s recent work has been inspired by the landscape and the changing seasons. Here, his friend Martin Gayford charts the painter’s deep and growing connection to the natural world

David Hockney drawing with his dog Ruby in the garden of his home in Normandy, France, 29 April 2020.

David Hockney’s fascination with spring is an accidental consequence of his friendship with Lucian Freud. During the early months of 2002, he walked through Holland Park every morning from his own London studio to Freud’s, where he was sitting for a portrait. For many years, Hockney had spent this part of the year in Los Angeles, but, this time, he stayed in Britain after Christmas and fulfilled his duties as a model.

During his walks through the park, he became aware of ‘something you miss in California because you don’t really get spring there’. In L.A., he explained, ‘If you know the flowers well, you notice a few coming out – but it’s not like northern Europe, where the transition from winter and the arrival of spring is a big, dramatic event’.

That was the point at which Hockney began to be spring-conscious. Since then, he has observed the changes of the yearly cycle with ever-increasing intensity and precision. So far, spring has been the subject of three enormous multipart works by Hockney, from 2011, 2013 and 2020, as well as many individual works from other dates in various media.

Spring is not Hockney’s sole preoccupation in terms of landscape, but he has given it special attention. The reason lies partly in the adjective he chooses to describe its manifestation in places such as Britain and Normandy: ‘dramatic’. Walt Disney and his team, Hockney likes to point out, completely missed the point in the 1940s animated musical anthology Fantasia. In one sequence they used music from Stravinsky’s Rite of Spring. ‘But they didn’t get what Stravinsky’s music was about – they used dinosaurs trampling about’. But the rhythmic elation and energy in the score, is ‘not dinosaurs pushing down, it’s nature coming up!’

The northern spring is a spectacular transformation, from bare branches to leaves and blossom, shoots surging out of the earth. The landscape alters almost from day to day. There is a point early on, Hockney noticed, when the first leaves come out, ‘They begin at the very bottom of the trees, and you don’t see very much of the branches, so the leaves seem to float.’

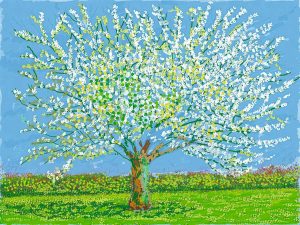

David Hockney No. 180, 11 April 2020 iPad painting. © David Hockney

Similarly, while working in East Yorkshire, Hockney noticed that, later on, there is ‘a moment when spring is full’. He dubbed this ‘nature’s erection’: ‘Every single plant, bud and flower seems to be standing up straight; then gravity starts to pull the vegetation down’.

As the shapes of the vegetation shift, so do the colours. For Hockney, one marker of the transition from spring to summer is the change in colour. Thus, in early June 2020 he insisted: ‘It’s still spring green here.’ That was towards the end of his most extensive spring cycle to date.

Part of the original impulse for his move to Normandy in 2019 was an urge to depict the blossom there (which he knew was exceptionally abundant). Hockney made some paintings and drawings of spring that initial year, but in 2020 he was poised and ready with a new, specially tailored app for his iPad.

Just as he began to draw, Covid and its attendant lockdown struck. The result was months of isolation, which offered Hockney an extraordinary opportunity to concentrate. In 2011 he produced some 50 pictures during the spring; in Normandy it was 120. What’s more, they were all derived from a much smaller area: just the few acres around his farmhouse. Consequently, this spring, the tenth that he chronicled, was, as he put it, ‘much more detailed’.

‘Here I’m living in the middle of my subject, whereas in Bridlington I had to drive there and that makes an enormous difference because I get to know the trees a lot better. I’m always looking at them. Always.’

This fascination with vegetation and weather, shapes of leaves, and the growth of flowers, is unusual. Many people scarcely notice this happening around them at all – even during lockdown. To some critics, Hockney’s interest in landscape painting seems bizarrely old-fashioned.

Over the last couple of decades, however, since Hockney began to look closely at the burgeoning plants in Holland Park, we have come to understand how crucial our relationship with nature truly is. The weather, the balance of the seasons, the sprouting of shoots and unfolding of leaves – nothing could be more important than these things.

As Hockney has said, if spring did not arrive, forcing its way up through the earth, we would have a cataclysmically serious problem. Far from being reactionary, Hockney’s preoccupation with observing the landscape has come to seem prophetic.

Source: Tate