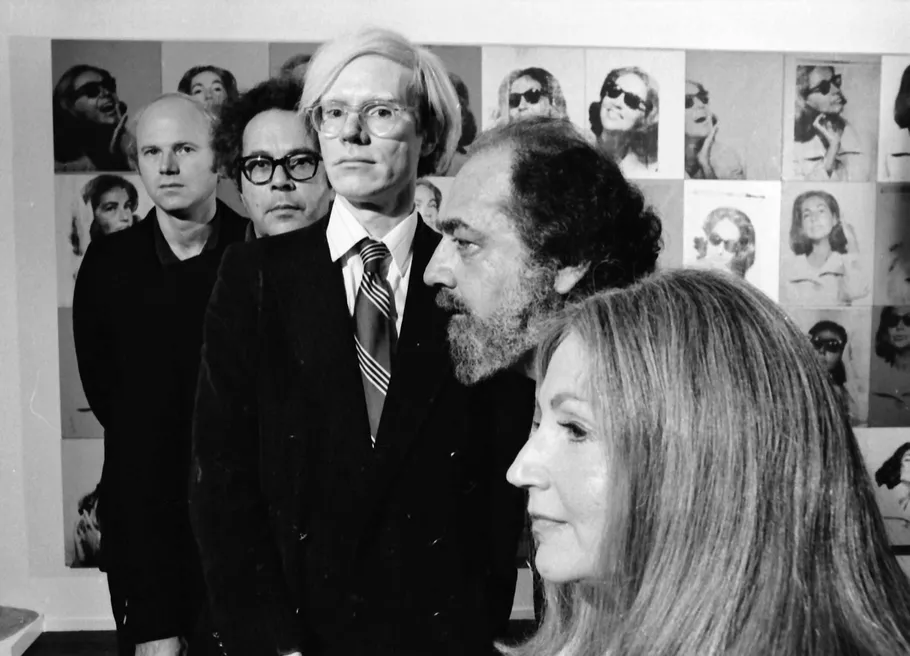

Andy Warhol photographed with art collectors Ethel and Robert Scull, sculptor George Segal, and painter James Rosenquist at the Scull’s residence in 1973. (Photo by Jack Mitchell/Getty Images)

Many common complaints about today’s contemporary art market—the billions of dollars sloshing around the market, the spectacle-driven fairs, the speculators and profit-seekers buying up works by young artists, the relentless marketing by auction houses—can be traced to the actions of one Robert C. Scull.

Scull, a New York taxicab impresario and passionate collector of Abstract Expressionist and Pop Art, sold 50 of his best paintings at Sotheby Parke Bernet on October 18, 1973, in an auction that “heralded the beginning of a new era in the art world: a hyper-commercialized art market focused on promoting and selling contemporary art,” according to Doug Woodham, author of the book “Art Collecting Today.” The famous, or infamous, Scull sale does, in hindsight, look like a turning point. It demanded copious amounts of marketing and publicity, launched prices for living artists into new territory, and catalyzed an ongoing debate on artist resale royalties.

Understanding how the Scull auction departed from the norm can help illuminate how today’s market operates. Here are three ways the sale helped shape today’s art market.

George Segal, The Dancers, 1971

The Scull sale put post-war and contemporary art on the map, price-wise.

Andy Warhol. Jasper Johns. Robert Rauschenberg. Franz Kline. Frank Stella. Do any of these names ring a bell? Scull and his wife Ethel collected these artists long before they became touchstones of Art History 101. In the 1960s and 1970s, they were still just bright young things, represented and promoted by equally bright young dealers, such as the legendary Leo Castelli and his wife Ileana Sonnabend. In the documentary The Mona Lisa Curse, Scull is described as paying $1,000 to $2,000 on average for a Johns or a Rauschenberg, and often buying several works at a time.

That’s not to say the dealers were naive: Castelli and Sonnabend excelled at getting their artists press coverage and shown in museums, and the Pop Art movement was starting to take off. Collectors knew the work and wanted to own it.

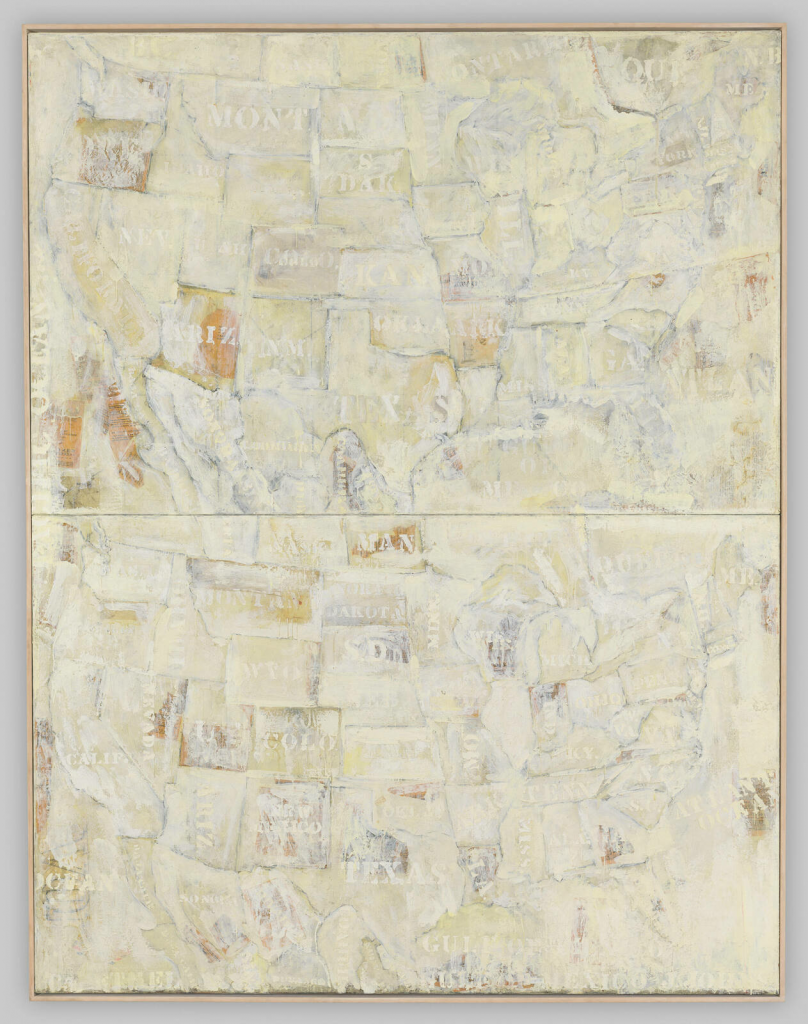

Jasper Johns, Two Maps, 1965

The results were extraordinary. At the auction, the works sold for many multiples of their purchase prices, reaching a then-unheard of total of $2.2 million, or just under $12 million in today’s dollars. A painting by Cy Twombly sold for $40,000, over 50 times the $750 Scull paid. A Jasper Johns painting, Double White Map, went for $240,000. Scull had bought it for $10,200. These were record sales for living artists.

The sale “established the idea that modern art could be a really effective money-making tool,” says Barbara Haskell, a curator at the Whitney Museum of American Art. It was not just a watershed moment for certain branded artists, who still top charts of the highest-performing artists at auction, but “the whole field of contemporary art got the stamp.…It changed the whole idea that you could make a lot of money from art,” she says.

Marketing and publicity moved to the center.

Many of the artists in the sale, such as Warhol or Roy Lichtenstein, were already well-known, according to Haskell, laying the groundwork for Scull’s high-intensity marketing. “The public had already embraced Pop Art,” said Haskell. “It was accessible and something everyone knew about, so the sale built on that momentum.”

But Scull had a few tricks up his sleeve. He was already known as a brilliant publicist with respect to his taxi business, famously hiring etiquette expert Amy Vanderbilt to teach his cab drivers manners in a lesson held at the Waldorf Astoria, an event covered, naturally, by a group of invited reporters. Ethel Scull entered the auction in a long black Halston gown with the taxi fleet’s logo—“Scull’s Angels”—on her chest. Angry protesters outside supplied tension and drama. A lavish catalogue, hardbound and featuring multiple fold-out pages illustrating the works, was a rare investment for living artists. And Rauschenberg, possibly drunk, confronted Scull about his supposed profiteering (more below) from artists’ works.

Franz Kline, Mahoning, 1956

CBS news reported on the auction, and a documentary film crew was in tow. In the film, America’s Pop Collector: Robert C. Scull—Contemporary Art at Auction, art historian Baruch Kirschenbaum writes, “The auction is seen not simply as self-contained historical occurrence, but as a media event.”

“Between the catalogue, the media campaign, the parties—I think Scull was really a master of” generating publicity, said Woodham. While auction houses previously may have turned up the publicity every now and then for an Old Masters sale of some exclusive pieces from a duke or duchess, the Scull sale “absolutely set a new standard for post-war and contemporary.”

And that was largely thanks to Scull himself, although the art world quickly absorbed the lesson.

“The guy knew how to create a marketing machine to support his business, and to promote their own personal brand, if you will,” says Woodham. “And the art world saw the Scull auction and said, ‘This is how to do it.’”

With prices reaching new levels, artists wondered where their cut was.

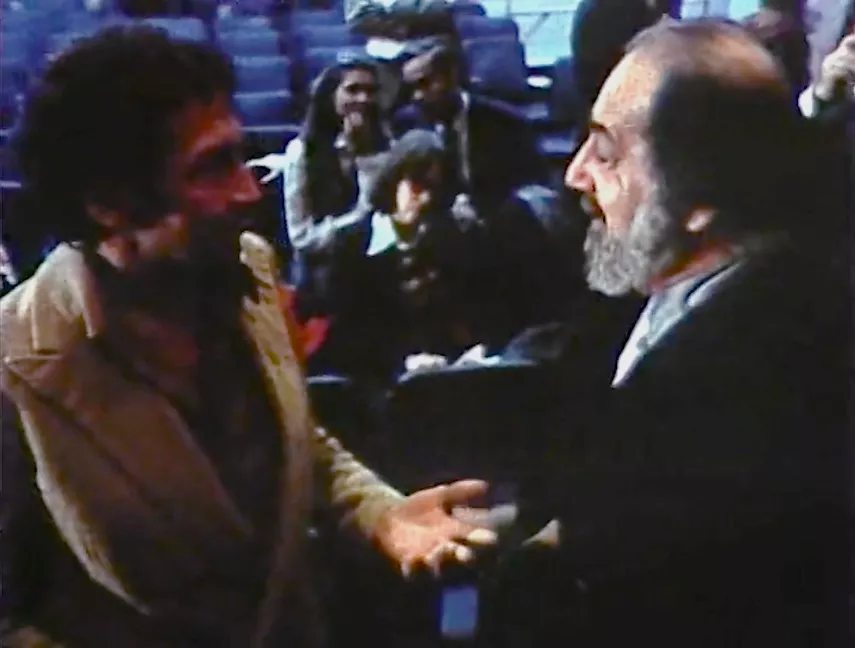

The novel prices achieved at the Scull auction highlighted the gap between what artists earned selling their work and what a shrewd collector could make by selling the same items. Rauschenberg’s Thaw combine, sold to Scull for $900, went for $85,000. Following the sale, Rauschenberg famously confronted Scull, annoyed that Scull was reaping thousands of dollars while the artist was “working [his] ass off.” But as Art Market Monitor’s Marion Maneker points out, Scull was quick to remind Rauschenberg that the high prices would eventually redound to the artist. “The sale set a new price level to Rauschenberg’s direct benefit,” Maneker writes. Woodham suspects that “the artists were probably happy, since what they were producing seemed to now be worth a whole lot more.”

Robert Rauschenberg, Small Rebus, 1956

Still from the 1973 Scull Auction, via “The Art Market, Explained: How and Why a Patron Supports an Artist,” directed by Oscar Boyson for Artsy, in collaboration with UBS.

Regardless of whether the sale enraged or delighted the artists in question, it revived a debate over whether artists should receive royalties on sales of their work. The following year, art historian Robert Hughes proposed in TIME a federally legislated mandatory artists’ resale royalties program. “The hitch in an informal royalty system is simple: any one who thinks a collector will voluntarily give a 15% cut on resale back to the artist simply does not know collectors,” he wrote. “If there are to be any royalty assurances, then, they can only work if they are written into U.S. law.”

Nearly half a century on, that still hasn’t happened in the U.S., and a state-level effort in California appears to have had little impact. That’s despite auction results for post-war and contemporary art that regularly reach the hundreds of millions of dollars.

And other aspects of the sale might also look familiar, from the crowd of women artists protesting outside (only one of the artists in the sale, Lee Bontecou, was female), to the still-unresolved tension between art’s bohemian spirit, artists’ frequently modest living conditions, and the vast wealth of collectors and some dealers (one protest sign outside read, “Never Trust a Rich Hippie”).

“People are still complaining about these things,” Woodham says. “It struck me how nothing changes.”

Lee Bontecou, Untitled, 1961

Source: Artsy