Curator Gražina Subelytė talks to Christie’s about the role of the occult in the Surrealists’ lives and art — and why their response to global conflict seems as relevant as ever.

Leonora Carrington ‘I piaceri di Dagoberto (The Pleasures of Dagobert)’ 1945. Egg tempera on masonite. 74.9 × 86.7 cm

It is now almost a century since André Breton penned the first Manifesto of Surrealism, in 1924. In the intervening years, myriad books have been written about the movement, and myriad exhibitions staged.

However, according to the co-curator of a new show at the Peggy Guggenheim Collection, in Venice, one key aspect of Surrealism has long been overlooked. Namely, the interest of so many of its artists in magic and the occult — and how their imagery was influenced as a result.

Surrealism and Magic: Enchanted Modernity features 60 works, with more than three-quarters on loan from museums and private collections worldwide, and a core of pictures from the rich Surrealist holdings of the Peggy Guggenheim Collection itself.

Here, we speak to the exhibition’s co-curator, Gražina Subelytė, about witchcraft, Tarot cards and a truly momentous reunion.

Where did the idea for this exhibition come from?

Gražina Subelytė: It arose out of my engagement with the work of the Swiss artist Kurt Seligmann, who moved to Paris in the late 1920s and became part of the Surrealist circle. He was an expert in magic and the occult, and acted as a mentor for many Surrealists on those topics — including André Breton, Remedios Varo and Leonora Carrington.

Kurt Seligmann ‘Baphomet’ 1948. Oil on canvas. 122.6 × 147.6 cm

When Seligmann and Breton were both were living in exile in New York during the Second World War, for example, Seligmann helped Breton with the writing of his esoteric book, Arcanum 17. This shared Breton’s hope for the renewal of society through an occult vision of woman as a gateway to spiritual purification.

Seligmann is represented in the exhibition by four paintings. His art is replete with symbolism, alluding to alchemy, witchcraft and the Kabbalah. In 1948 he published a book now considered a classic, The Mirror of Magic, an entire history of the occult in the Western world.

Giorgio de Chirico ‘Il cervello del bambino (The Child’s Brain)’ 1914. Oil on canvas. 60 × 65 cm

After using Seligmann as our starting point, further research for this show revealed that an interest in magic was common to a great number of Surrealists, from René Magritte to Dorothea Tanning.

How does your thesis fit into the more general understanding of Surrealism?

GS: Pretty neatly, I think. It’s not subverting everything you’ve ever been told about the movement; it’s adding to it. Surrealism was born in the aftermath of the First World War, as a rebellion against the supposedly rationalist society that had just brought about mass slaughter.

As conventionally understood, its artists and writers began looking towards the alternative reality of dreams and the subconscious for inspiration. One might say that magic and the occult offered a parallel alternative reality. No Surrealist was happy with the world they actually inhabited.

Leonor Fini ‘La fine del mondo (Ends of the Earth)’ 1949. Oil on canvas. 35 × 28 cm

Did artists partake in actual acts of magic themselves?

GS: Some did. We know that Seligmann and the Italian Surrealist, Enrico Donati, for example, followed a 16th-century ritual devised by the English occultists, John Dee and Edward Kelly, aimed at summoning the dead.

I could also mention Remedios Varo and Leonora Carrington, good friends who from the early 1940s onwards were both living in Mexico. Varo spoke of the pair’s engagement in witchcraft ‘in isolated areas of the country where [it was] still practiced’. Sadly, precise details of that engagement are uncharted.

Could you tell us about a standout work or two from the show?

GS: The show covers a period of around 60 years. The earliest piece is by the proto-Surrealist, Giorgio de Chirico, from 1914, and the most recent piece dates to the mid-1970s.

Max Ernst ‘La vestizione della sposa (Attirement of the Bride)’ 1940. Oil on canvas 129.6 × 96.3 cm

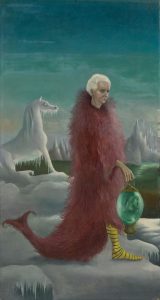

Two of my favourite paintings are Max Ernst’s Attirement of the Bride (1940), depicting the artist’s lover, Leonora Carrington, as a semi-naked bride partially wrapped in a mantle of red feathers; and Carrington’s own Portrait of Max Ernst (1939), in which her subject is dressed from head to toe in a similar mantle. (Interestingly, the outfit in the former comes complete with an avian head, and that in the latter with a fish tail.) The two pictures can be considered complementary and, happily, are being reunited for the first time in 80 years.

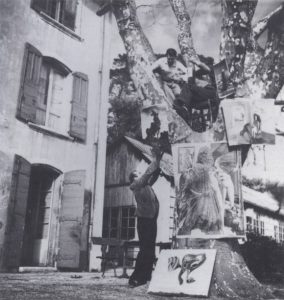

There is a photograph from 1941 of Ernst preparing for an auction at Villa Air-Bel, a chateau in the suburbs of Marseilles where many Surrealists waited for the papers necessary to leave war-torn Europe for the Americas. Ernst hung a few of his and Carrington’s paintings from a tree, including Attirement of the Bride and Portrait of Max Ernst. They haven’t been seen together since… until now.

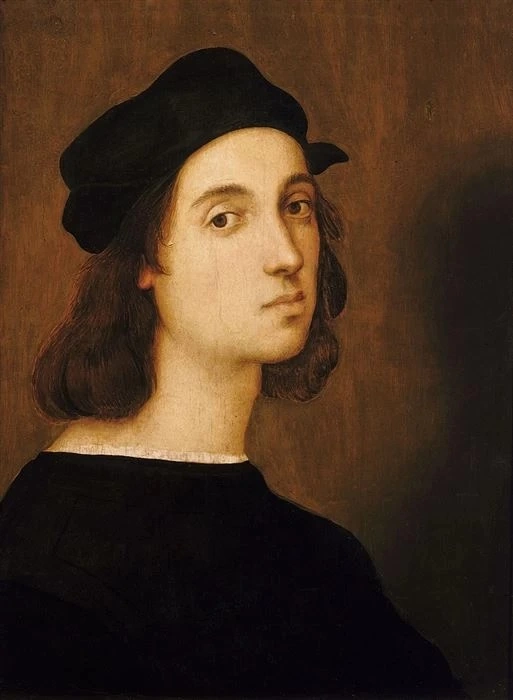

Leonora Carrington ‘Ritratto di Max Ernst (Portrait of Max Ernst)’ ca. 1939. Oil on canvas 50.3 × 26.8 cm

Ernst used to call Carrington his ‘Bride of the Wind’ — a nickname inspired by a witch-like being from medieval lore — and one assumes he may be alluding to that in his picture. Carrington, meanwhile, captures Ernst as an alchemist-hermit holding a lantern. He distinctly resembles the character of ‘The Hermit’ in the traditional deck of Tarot cards.

The two works highlight the general artistic exchange and shared interests between the couple — as well as, in this specific instance, Carrington’s influence on Ernst, since her portrait of him was painted first.

Jacques Hérold (standing), Max Ernst and Danny Bénédite, Varian Fry’s associate, hang paintings by Max Ernst and Leonora Carrington from a tree for an auction of art works, Villa Air-Bel, Marseilles, 1941

Is it true that certain Surrealists adopted the artistic persona of a kind of alchemist, enchantress or seer?

GS: Yes, their interest in magic in some cases extended to that. Argentinian-born Leonor Fini is a good example, Romania’s Victor Brauner also.

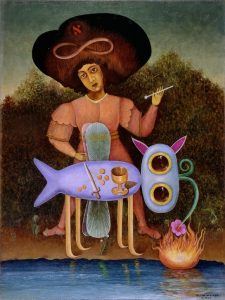

In his 1947 painting, The Surrealist, below, Brauner depicts himself as a young magician. He wears a large hat and stands behind a table with a knife, a goblet and a handful of coins on it. The image is derived from that on the card of the Juggler (also known as the Magician) in traditional Tarot decks.

Victor Brauner ‘Il surrealista (The Surrealist)’ 1947. Oil on canvas 60 × 45 cm

The Juggler card signals a capacity to fulfil one’s creative power as a way of controlling one’s life. Magic helped Brauner attain the artistic liberty needed for such fulfilment, freeing his mind from limits that might hold it back from exploring its potential.

Do the paintings in the exhibition still have something to say to us today?

GS: Absolutely. Surrealism can sometimes be looked back upon nowadays as a movement that was a little quirky and perhaps lacking seriousness. But I hope this exhibition proves something different was true.

In 2022 — a time of pandemic, climate chaos, and another war on European soil — perhaps it’s easier for us than it was in previous years to connect to the mindset of the Surrealists. They made their art in the context of two world wars. Is it any wonder that they sought a form of escape and self-empowerment through dreams or magic?

Source: Christie’s