England-born, LA based British-Iranian artist Kour Pour – famous for his series of carpet paintings – delves into the rich history of Persian rugs, unshackling and readdressing cultural categorisations. And he makes something both historic and entirely new. From a youth spent climbing up piles of Persian rugs in his father’s shop, to Iran’s historical and current politics, to the voices of hip-hop music, Kour Pour chats to Isabella Fergusson about the many inspirations woven into his intercultural, intertemporal artworks

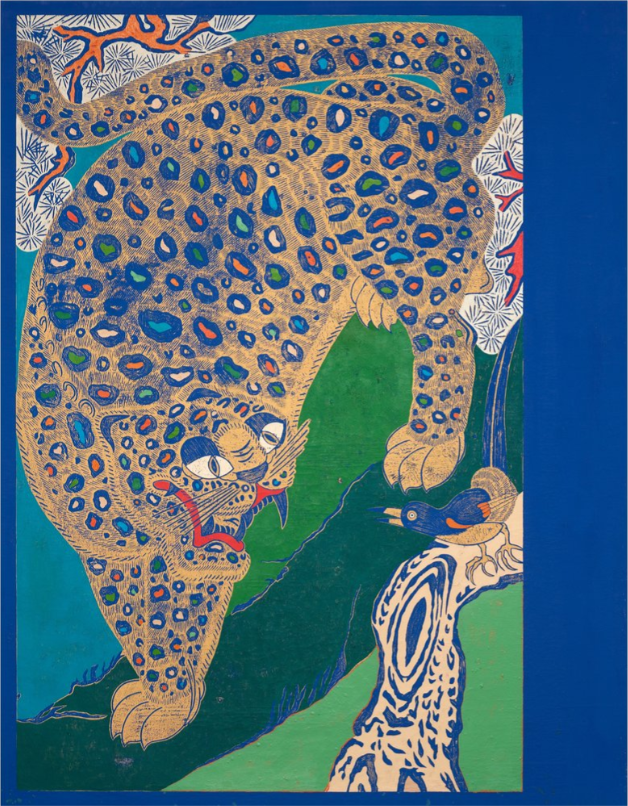

Age of Discovery, 2017, Acrylic on canvas over panel, 65″ x 53″

LUX: You were born in Exeter, England, but moved to LA. What effect does place – and did the move – have on your art?

Kour Pour: I very naturally respond to my surroundings in my work – images and materials I come across around the world make their way into the studio. I think it’s safe to say that Los Angeles and everything that I encounter here finds a way into my practice. My community here is incredibly diverse, and all the people that find their way into my life influence my practice. Exeter was beautiful, but it was quite homogenous. Moving from Devon to LA helped to open my world up.

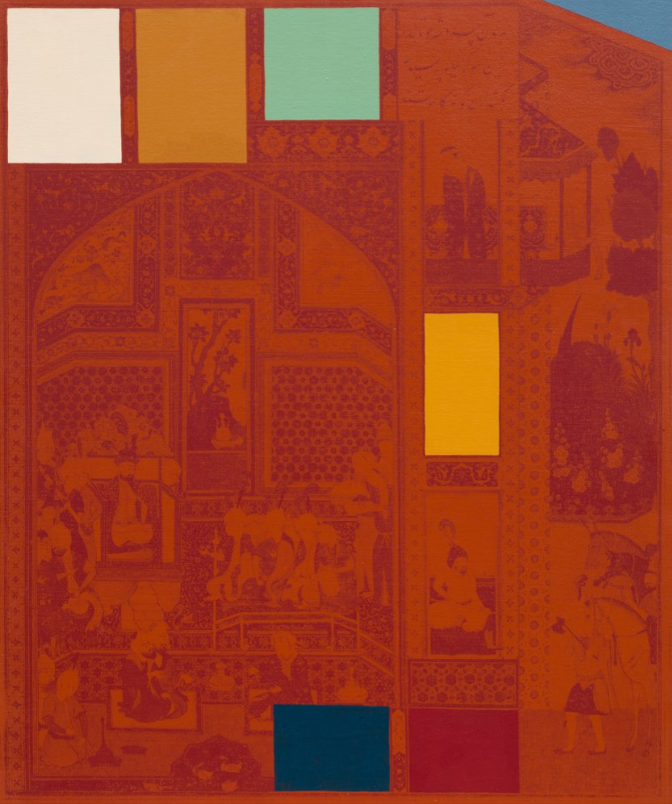

Autumn Hunting Scene, 2016, Acrylic on canvas over panel, 96” x 72”

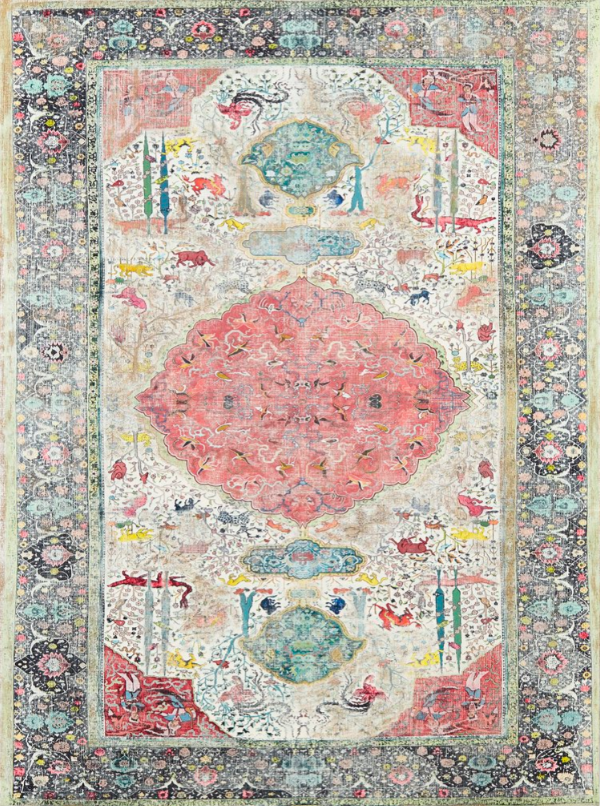

Dragons & Genies, 2012-2013, Acrylic on canvas over panel, 96″ x 72″

LUX: You’ve exhibited all around the world; where do you feel that audiences most resonate with your works? Is it very different across these places?

KP: The nature of my practice is that it’s quite varied: I make paintings and sculptures and large-scale prints, and these can range from hyper-figurative to hyper-abstract. My experience has been that this allows everyone to have a different access point to my work, and that it promotes resonances across different cultures and geographies. I think of my different bodies of work as different languages, and therefore that allows me to have a conversation with as many people as possible.

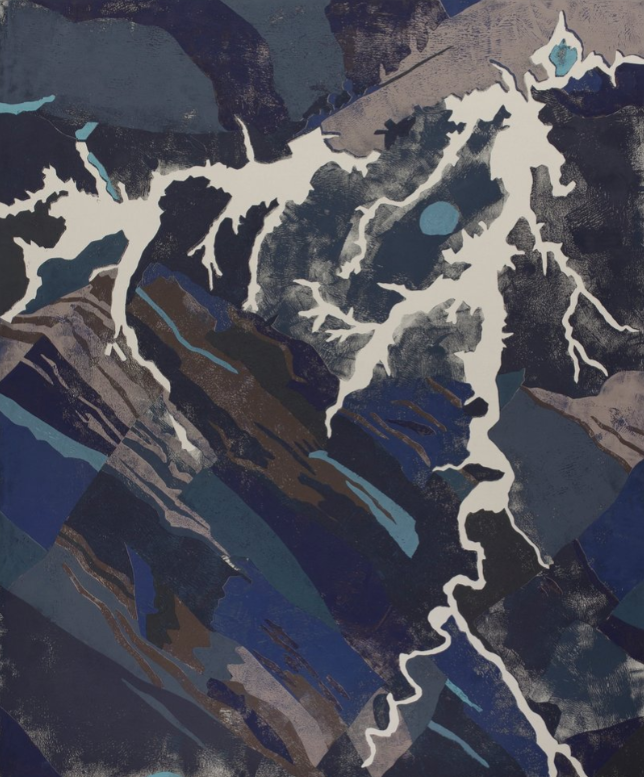

Earthquake, 2015, Block printing ink on canvas, 82.5″ x 77″

LUX: Tell me about your father’s carpet shop – your earliest memories there, its inspirations for your work now.

KP: My father moved to Exeter by himself when he was 14 – a result of the Iranian Revolution in ’79. Eventually his older brother joined him, but the two of them were teenagers in a new country without a support system. So, they had a typical immigrant experience of arriving in a new place and just having to figure it out. My father eventually rented a storefront that had many different lives when I was growing up: a sunglass store, and ice cream shop. That one was my favorite. But when I was about 4 or 5, it was a carpet store. I remember being a child and climbing around all the rugs and feeling that they made a place seem like home. I also remember my father touching up old and faded carpets by hand using natural dyes. That was probably one of the first times I was exposed to painting, in any form.

Flames 1, 2018, Block printing ink on canvas over four panels, 48″ x 77.25″

Flames 2, 2018, Block printing ink on canvas over five panels, 48″ x 95.5″

LUX: You’ve said before that you wished museum collections wouldn’t be separated by geographic location or time period, which throws up the challenge of overly constrictive categorisation, particularly in the case of your work. But where would you place your art if it had to be geographically categorised – by its inspiration, or the location it was painted, or your descent? Perhaps it simply cannot comfortably be boxed up…

KP: I don’t want to categorise the work. One of the beautiful things about art is that you can find relationships across temporal and geographic boundaries. I want to allow my work that freedom.

Geometric Painting 19, 2018, Acrylic on canvas over panel, 30″ x 25″

LUX: I was speaking to an artist yesterday that said that a painter has to confront and get over the fact that what he does is – in absolute terms – utterly pointless. Do you agree? Have you had to to confront a sense of uselessness?

KP: Maybe an artist that has nothing to say in their work could feel that painting is pointless, but I absolutely disagree with that notion. Art is a healer. Whether for the artist or the viewer, the act of creating is therapeutic and experiencing someone else communicate through any medium is both thrilling and comforting. It’s an expression of being alive. There are so many things art can do. It raises awareness, it becomes a record of a time, it tells stories, and it imagines alternative ways of being. Art is endless in its possibilities.

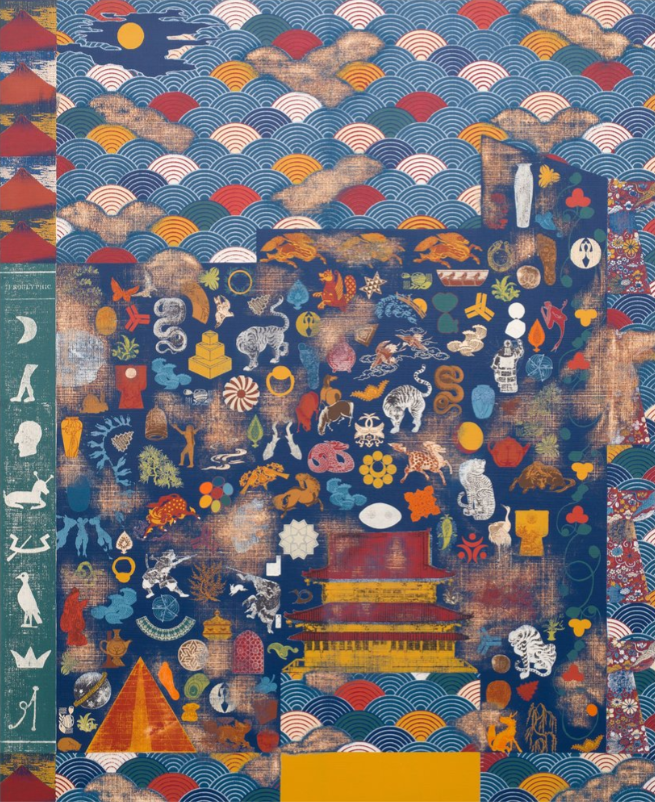

Jade Tiger, 2021, Block printing ink, acrylic and oil on canvas, 94″ x 76″

LUX: Should art’s political role be more respected – and is art, or should it be, inherently political?

KP: Art is made by people. Some individuals exist in worlds that are heavily politicized, and some don’t. Artists make work that is, directly or indirectly, a reflection of their reality, so you could argue that art is always social and political.

Miyako, 2015, Block printing ink on canvas, 81″ x 67″

LUX: How do your Iranian roots play into your work?

KP: My Iranian identity has always been a big part of how I navigate my reality. It has influenced both how I’ve engaged with the world, and how the world has engaged with me. I’ve used Iranian imagery in my own practice, and that identity has also guided some projects that are not directly related to what I’m doing in the studio. In 2022, I opened an exhibition project space in my studio complex in Inglewood, called Guest House. The first show was of Iranian artists living in Los Angeles, born out of what I perceived as a lack of engagement with the Iranian community by the city’s art scene. Which is crazy, given how many Iranians there are in LA – the city has the largest population living outside of Iran.

Mystic Waves (Seigaiha), 2019, Acrylic on canvas over panel, 65″ x 53″

Two weeks after we opened the exhibition, the Woman, Life, Freedom protests broke out after Jina Mahsa Amini’s death in Tehran. Guest House immediately became a hub for the community. We would have people come visit the show and trade news about what was going on back home in Iran, we had film screenings, and we tried to respond in whatever way we could to what was going on. That sense of community, and the relationships that I made over the course of that first exhibition, have entered the studio and now help inform the totality of my studio practice.

Peacock Tiger, 2021, Block printing ink, acrylic and oil on canvas, 94″ x 76″

LUX: Hip-hop and carpet painting seem an unlikely combination. What about the music inspires you, and is it hip-hop’s differences or similarities to your medium which feed your works?

KP: One of the things that initially drew me to hip hop was the idea of sampling: taking a sound from a song, transforming it, and adding it into another song. This matches up with the way that the carpets I’m interested in were made: images would travel along the Silk Road and there would be this incredible intermixing of cultures. A single rug that was assigned Persian origin would have images from as far west as Venice and as far east as China. I think that the language around sampling in hip hop is a perfect way to speak about these works.

Interviewer: Isabella Fergusson

Source: Lux Magazine