From graffiti renegade to Warhol protégé and New York Times cover star, the life and career of a 20th-century icon

Although his life was tragically cut short, Jean-Michel Basquiat’s raw, radical paintings made a lasting impact in the art world and beyond. Here, we retrace the life and work of the man who, in just eight years, became a 20th-century icon.

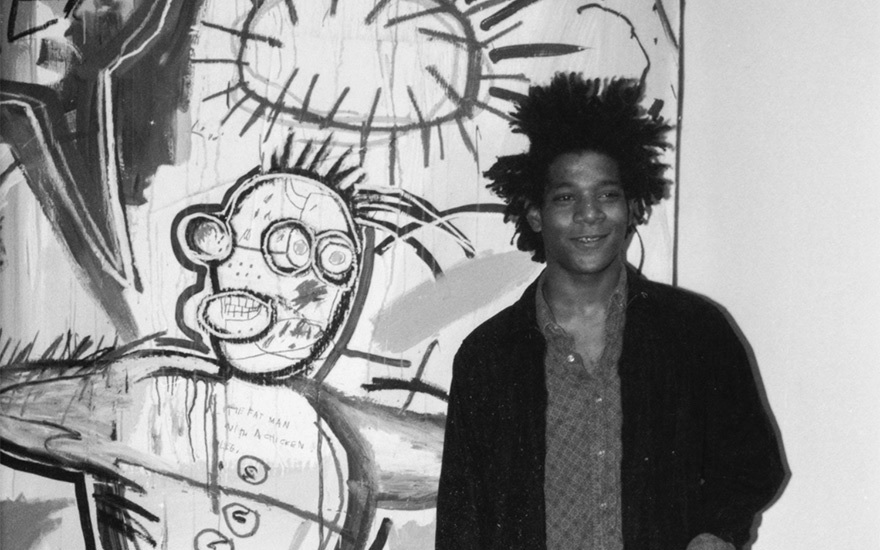

Jean-Michel Basquiat (1960-1988) ‘Donut Revenge’ 1982

A precocious child

Basquiat was born in Brooklyn, New York, on 22 December 1960, to a Puerto Rican mother and a Haitian father. He was the second of four children; he had two younger sisters, and an older brother who died not long before his birth.

He was drawn to art from a young age. His mother, Matilde, appreciated his talent, and encouraged his interest by signing him up as a young member of the Brooklyn Museum of Art. By age 11, he was fluent in French and Spanish, as well as English.

At the age of six, Basquiat was hit by a car; his arm was broken and he underwent several surgeries. While recovering, his mother bought him a copy of Gray’s Anatomy, the 19th-century medical textbook. This would have a lasting influence on his work.

When he was 13 years old, Basquiat’s mother was committed to a mental institution; she would be in and out of institutions for years thereafter. Basquiat attended an alternative Manhattan high school, City-as-School, geared towards the talented and the contrary — where he famously threw a pie in the face of the principal. Eventually, he began spending time around the School of Visual Arts, where he befriended students Keith Haring and Kenny Scharf.

SAMO — a shared graffiti tag

From 1978, Basquiat’s graffiti’d SAMO tag (a pseudonym, shared with his friend Al Diaz, which stood for ‘same old shit’) began appearing around Lower Manhattan — and occasionally on the cars of the D train he rode home to Brooklyn. The epigrams eventually caught the eye of The Village Voice, which published a piece about them. Basquiat and Diaz eventually fell out, and SAMO came to an end in 1979. Despite his early association with graffiti, Basquiat never considered himself a graffiti artist.

Jean-Michel Basquiat (1960-1988) ‘The Guilt of Gold Teeth’ 1982

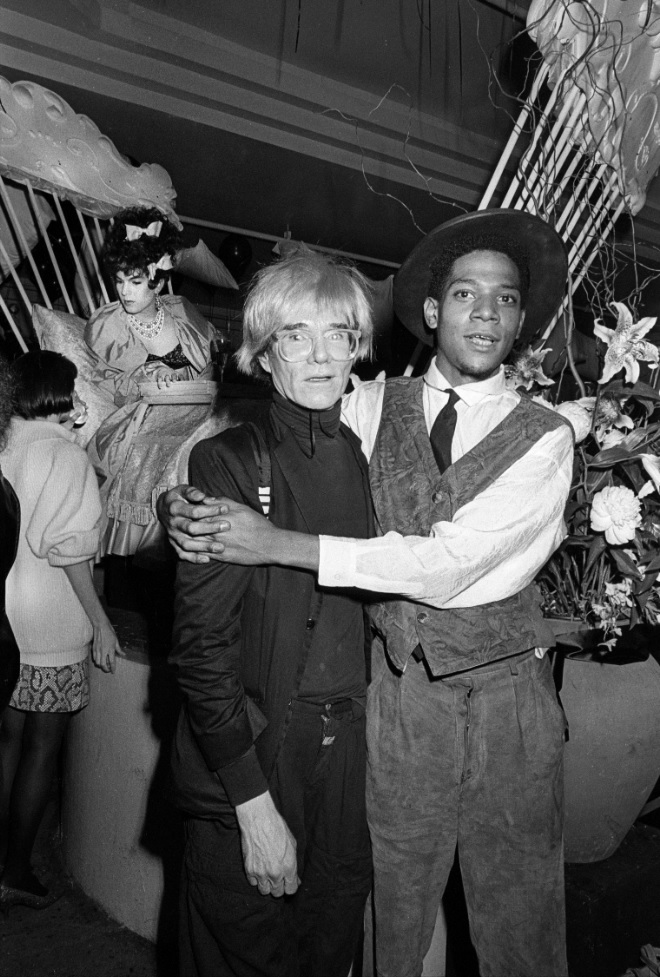

Feeding off each other: Basquiat and Warhol

Basquiat had long revered the legendary Pop artist Andy Warhol. In 1980, they met at a Soho restaurant, and Basquiat showed him a copy of one of his photo collages. The two met again two years later, when Basquiat’s art dealer Bruno Bischofberger brought him to Warhol’s Factory. Warhol was impressed with the young artist; the two soon began to work together, and became close friends.

Between 1983 and 1985 they collaborated on several paintings. According to Ronnie Cutrone, one of Warhol’s studio assistants, ‘The relationship was symbiotic. Jean-Michel thought he needed Andy’s fame, and Andy thought he needed Jean-Michel’s new blood. Jean-Michel gave Andy a rebellious image again.’

Jean-Michel Basquiat and Andy Warhol, Area, New York, 1984. Photo: © Ben Buchanan / Bridgeman Images

‘The first radical art show of the ’80s’

Basquiat’s big break came in June 1980, when his work was included in The Times Square Show, a multi-artist exhibition curated by radical New York collective Colab and Fashion Moda, a South Bronx community arts space. Staged in an abandoned midtown building, the show also included works by Kenny Scharf, Jenny Holzer, Nan Goldin and Keith Haring.

The media attention generated by that show helped launch Basquiat’s career. The Village Voice called it ‘the first radical art show of the ’80s’. Jeffrey Deitch wrote in Art in America that ‘a patch of wall painted by SAMO, the omnipresent graffiti sloganeer, was a knockout combination of de Kooning and subway spray-paint scribbles.’

In 1981, Basquiat was invited to join the gallery run by Annina Nosei, who had been greatly impressed with his work after seeing it in the groundbreaking New York/ New Wave show at PS1 earlier that year.

It was here, in a basement studio with a large skylight below the gallery, that Basquiat would paint, in Nosei’s words, a ‘number of masterpieces that brought him to the attention of the entire art world’. Donut Revenge was among them.

1982: A first solo show and the launch to superstardom

In 1982, things went from good to better. In March, Nosei hosted his first solo show, which sold out. Basquiat then travelled to Modena, Italy, and the paintings he produced there — Untitled, Profit I and Boy and Dog in a Johnnypump — are considered among his most important pieces.

In fact, eight of the 10 world auction records for the artist are held by works from 1981 to 1983, including the top seller In This Case (1983), which was purchased for $93.1 million in May 2021 at Christie’s in New York.

In June 1982, Basquiat exhibited at Documenta VII in Kassel; in December, Artforum magazine published an essay on the young artist, launching him to superstardom.

Jean-Michel Basquiat (1960–1988) ‘Warrior’ 1982

With Madonna and meeting Rauschenberg in California

Also in 1982, Basquiat spent time on the West coast, working in a space below Larry Gagosian’s California home. This led to his second show at the Gagosian Gallery in Los Angeles, in 1983. But he was not the only soon-to-be-famous guest under Gagosian’s roof: Basquiat brought along his then-girlfriend, an up-and-coming singer called Madonna. ‘He told me, “She’s going to be a big, big star’’,’ Gagosian later recalled.

In California, Basquiat was drawn to the pieces Robert Rauschenberg was producing at the renowned print studio Gemini G.E.L. Basquiat visited Rauschenberg several times, and would continue to draw inspiration from the Abstract Expressionist artist.

A new champion hailed by The New Yorker

Basquiat’s work resonated with many in the art world who were eager to cast off the Minimalist trend that had dominated the late 1960s and 1970s. In Basquiat, a key member of the Neo-Expressionist movement, they found a new champion. As The New Yorker critic Peter Schjeldahl would later write of Basquiat’s paintings from 1982, ‘You can’t learn to do this stuff. It’s about talent, served by commensurate desire and concentration — and joy.’ Basquiat, said Schjeldahl, was ‘a painter to the core’.

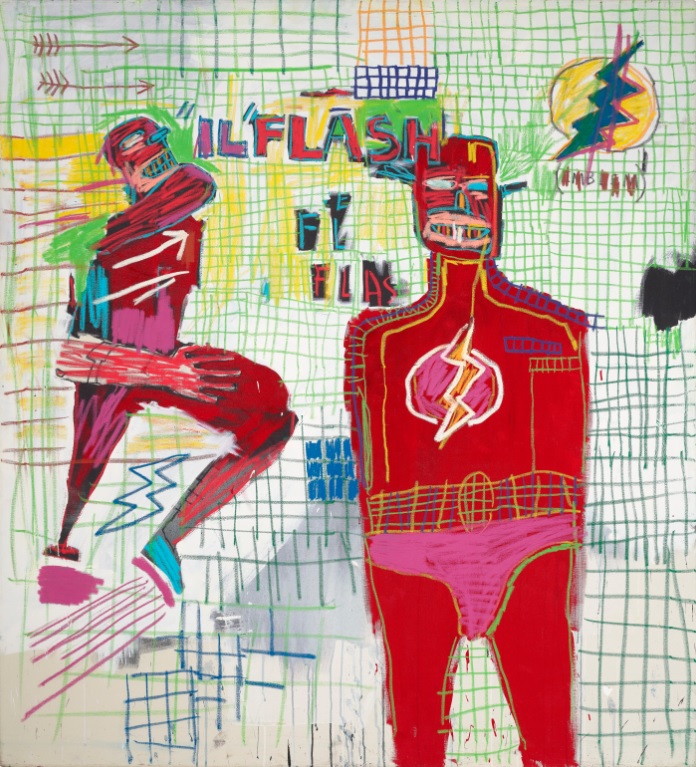

Jazz and blues heroes and a legendary hip-hop record

Music, and jazz in particular, was crucial to Basquiat’s work. His art offered a vibrant visual counterpart to the prevailing emphasis on improvisation, non-linear structure and sampling. His paintings frequently celebrated his favourite jazz heroes, such as Charlie Parker, in much the same way that he paid artistic tribute to famous athletes, boxers and other personal icons, many of whom struggled to gain the recognition of their white counterparts.

Equally key for Basquiat was hip-hop, the emergence of which paralleled Basquiat’s own artistic rise. In 1981, he made a cameo appearance as a DJ in the video for Blondie’s chart-topping single, Rapture — the first rap video ever broadcast on MTV. He also produced a legendary hip-hop record, Beat Bop, a rap battle between MCs K-Rob and Rammellzee, illustrated with Basquiat’s own art. With original copies extremely rare, it has become one of the most sought-after rap records ever made.

Jean-Michel Basquiat (1960-1988) ‘Flash in Naples’ 1983

‘I didn’t see many paintings with black people in them’

Basquiat was one of few African Americans in a predominantly white art world. Throughout his career, his deeply political art foregrounded blackness, and the ordeals and traumas experienced by black people in America. His focus on black culture was atypical of many artists at the time, and his work helped bring attention to the lack of diversity in the art world.

According to the scholar Richard Marshall, Basquiat ‘continually selected and injected into his works words which held charged references and meanings — particularly to his deep-rooted concerns about race, human rights, the creation of power and wealth.’

‘I realised that I didn’t see many paintings with black people in them,’ Basquiat himself explained, later adding, ‘the black person is the protagonist in most of my paintings.’

Jean-Michel Basquiat (1960-1988) ‘In This Case’ 1983

‘Royalty and the streets’ — Basquiat as regal warrior

Along with the boxer, the king is one of Basquiat’s most enduring motifs. He began using the crown as his signature when he co-opted the doors of SoHo art galleries as his canvases. Early on, Basquiat described his subject matter as ‘royalty, heroism and the streets’; as his career progressed the early crowns developed into fully fledged figures in gleaming headgear. Basquiat’s regal warrior is, in part, an emblem of his success: Basquiat, ‘King of the Streets’, had conquered the art world.

Magazine covers — and battles with drug addiction

In 1983, at just 22 years old, Basquiat was included in the Whitney Biennial, becoming the youngest artist to have represented America in a major international exhibition of contemporary art. In 1985, he was featured on the cover of The New York Times Magazine. Basquiat was at the peak of his career — but was battling a severe drug addiction, which had led Nosei to stop representing him.

Many close to Basquiat would later say that only Warhol had been able to get Basquiat to rein in his drug use; when Warhol died, in 1987, Basquiat spiralled downwards. Basquiat died on 12 August, 1988, in New York City, of an overdose.

Acclaimed by musicians and movie stars

Today, Basquiat’s work appears in the collections of some of the music and movie world’s leading figures, including U2 bassist Adam Clayton, Jay-Z and Leonardo DiCaprio. The actor Johnny Depp, who offered eight paintings and drawings by Basquiat for auction at Christie’s in 2016, said of the artist, ‘Nothing can replace the warmth and immediacy of Basquiat’s poetry, or the absolute questions and truths that he delivered.’

Source: Christie’s