Christie’s Deputy Chairman on how he appraises incredible collections, such as those of Yves Saint Laurent, Elizabeth Taylor and the Rockefellers

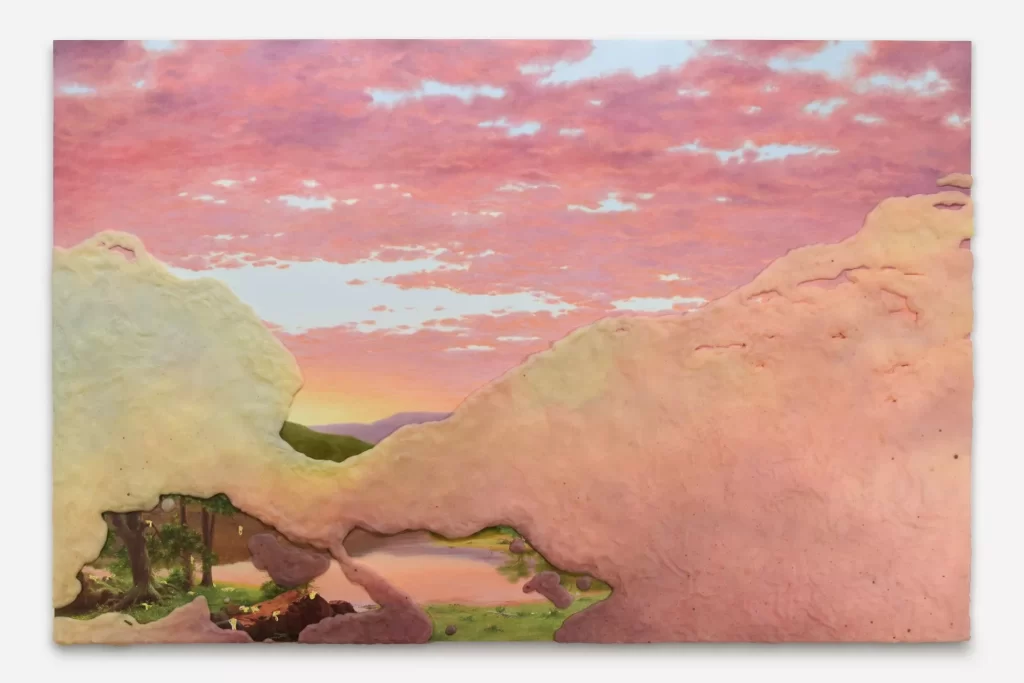

Not many people are obsessed with everything,’ says Jonathan Rendell, Deputy Chairman and Senior Advisor of Christie’s America. ‘I started at Christie’s 30 years ago and I have had many jobs, but gradually I moved from being a specialist to being more of a generalist.’

Generalism is a specialty all of its own, of course. And Rendell deploys this very particular skill in his role as an appraiser of collections that are difficult to appraise, such as the estates of celebrities or world figures.

‘I think most real collections are self-portraits — so it is a tremendous privilege to see them in the houses of their owners,’ he says. ‘And when they come to auction, that is what makes the difference between a regular mixed sale and a single-owner sale: the fact that there is a personality running through the whole thing.’

So when an important private collection is to be assessed, what is Rendell thinking of as he walks up the drive or goes up in the lift? ‘I like to go and see a house as early as possible, while the plants are still in the greenhouse, so to speak,’ he says. ‘It is important to get there before things have been tidied up; that way I am closer to the telling personal chaos, to the moment when time stopped.

‘I’ll be looking at the ensemble and the questions I am asking are: what’s the conversation that’s going on here? What is the intelligence behind it? I will have done my homework, of course, but I can still be lost for words. I was in a house recently where, as soon as I crossed the threshold I felt like I was eating chocolate cake while listening to organ music. It was sensory overload.’

Working in the apartment of Yves Saint Laurent was a particular highlight, says Rendell, because of the exquisite artistic sensibility expressed through the decor and the designer’s possessions. There, as in many houses that contain collections, the star piece was in the sitting room, where it could be admired by guests.

The salon of Yves Saint Laurent’s house at rue de Babylone, Paris, 2009

‘His Brancusi sculpture was that standout work. But the extraordinary thing was that there were layers and layers of things — great paintings, fantastic Art Deco furniture on which he displayed Renaissance sculpture or snuffboxes or crystals. And then snuffling around under all that was Moujik, Mr Saint Laurent’s dog.

‘I spent the best part of three months in Mr Saint Laurent’s apartment, and like everyone I fell in love with that dog. He was Moujik the Fourth; downstairs in the library were paintings of Moujik the Second — four portraits by Warhol, propped up against a bookcase.’

If a collection consists primarily of paintings, Rendell’s eye is naturally drawn to the fireplace when he walks into a collector’s principal drawing room.

‘In New York, there was a time when I’d look above the mantlepiece and find myself thinking: oh, this house is where that painting lives. Because people would put their paintings in the Met when they were away during the summer. Things were safer in a museum than in an empty house. So sometimes I would encounter a work in someone’s house that I had seen before in a museum exhibition.’

Dining rooms are no less social spaces than drawing rooms — but they are narrowly functional too. All the paraphernalia of a dinner party — the silverware and the dinner service — is art that is meant to be used.

According to Rendell, the dining room of the Peggy and David Rockefeller townhouse spoke volumes about how the family collected and how they enjoyed their friendships. ‘There were 65 different sets of porcelain,’ he says. ‘I think it is fair to say that they never saw a plate they didn’t like. And part of that love was trying to decide which service best suited the people who were coming to dinner.’

The dining room in the Rockefeller family’s New York City townhouse

Then there is the matter of how the porcelain was deployed on any given glittering evening. ‘It is fascinating to talk to the staff in different grand houses about what a place setting might have looked like. I will try to get the staff to recreate it if, say, we are planning a photoshoot for a catalogue. What you then get is a kind of performance piece: The Laying of the Table. And the pictures we take are a way of immortalising the ritual.’

So the very arrangement of Sèvres dishes and Eley dessert spoons can be part of the aesthetic legacy of a serious collector who is also a legendary host. Other relics of good times have less inherent value, but are deeply poignant nonetheless.

‘The house of Betsy Bloomingdale took me to a different time, a certain moment of optimism in California,’ Rendell explains. ‘The revelation to me there lay in her recipe books and her dinner party lists. She kept a food diary of every dinner that she had given — including who was sitting where at the table. That was magical. Once I saw those books I knew what the house was, what that big sunny house was made for.’

Sometimes the soul of the house resides in a more private spaces upstairs. Rendell recalls going to the house of Elizabeth Taylor, where ‘there were vast wardrobes. Miss Taylor knew that every time she left the house she was a movie star and she dressed accordingly to give her fans what they expected.

‘It was clear from the wardrobes alone that you would never see her out in Beverly Hills wearing jeans. She would be dressed as Elizabeth Taylor. There were a few works of art in the house — her father had dabbled in collecting and had a Van Gogh — but the jewellery collection was what made it extraordinary.’

Elizabeth Taylor’s wardrobe included a sizeable collection of handbags

Generally, says Rendell, the bedrooms of a grand house are unrevealing ‘unless you have something as beautiful as Mrs Dominique de Menil’s bedroom in Houston, which was the simplest and starkest — like a nun’s cell. It was wonderful because it was so pared down — and that was in a house decorated by Charles James.’

Rendell’s job as a specialist appraiser gives him a unique insight into the interior world of people who, in their lifetimes, were famous or historically important — other houses he has visited include the Reagans’, and the apartment of Lee Radziwill, sister of Jackie Kennedy (‘a New England sensibility with a touch of the exotic on top…’).

But his work begins at the moment when a collection amassed over a lifetime, or even generations, is about to go back out on the ocean currents of the art market and be dispersed forever. Is there not something a little sombre and elegiac about that?

The living room of Elizabeth Taylor’s house in Bel Air. Photo: Firooz Zahedi / Trunk Archive

‘Yes perhaps,’ says Rendell, and his thoughts turn back to the apartment of Yves Saint Laurent. ‘I was there for three months. The night before we were to start packing up, there was a drinks party for his gang of friends. The apartment was lit by candles and filled with lilies, his favourite flower. It was all ravishingly beautiful.

‘At a certain point everyone spontaneously went and stood in the garden. It was very odd: we all wanted to look in through the windows at what was going to disappear, to see it as a whole. Because the moment when you start to take things out, that is when the spell begins to dissipate. It is my job to keep that spell alive throughout the process whereby the objects make their journey to another collector, and a new home.’

‘I go into a house as an anthropologist looking for fetishes, seeking out the things that sum up the person to whom the objects belonged. Sometimes that thing might have little or no intrinsic worth at all — like the Rockefeller moneyclip. For me, that object said everything about the Rockefellers, about New York in the Thirties and Forties, about wealth and status. It was all in one tiny little thing.

‘And people will grab onto that. If you were a banker in Manhattan, wouldn’t you want to own a moneyclip that once belonged to the Rockefellers? It places you, the buyer, in the same relation to the object as the people who owned it before. That is why provenance is so important. Provenance is everything, in fact: where a piece comes from matters as much as what it is.’

‘I hadn’t been in New York for long when I was asked to appraise the contents of Rudolf Nureyev’s home. So I went to see the apartment, which was in the Dakota on the West Side. His presence in the rooms was palpable, you felt he was going to walk in at any moment, and that was because everything in the apartment was entirely his taste.

The salon of Rudolf Nureyev’s apartment in New York, 1995

‘The contents of the apartment had that Russian richness, a pattern-on-pattern thing. He loved carpets, he loved prints, he loved colour. There were great piles of textiles, and it was very lavish.

‘I could see that he pampered himself, that he liked that sense of being wrapped in a fur coat. It was fabulous — and sad too, because he died before his time. That element of melancholy is also absolutely Russian.

The dining room of Rudolf Nureyev’s apartment in New York, 1995

‘Just before the sale we had a party at the old Christie’s premises on Park Avenue. It was absolutely jammed with his friends, and there was a balalaika band playing in the corner. It was a celebration of the man, and rather over the top. That appreciation is something that I love.’

Source: Christie’s