As Christie’s wrapped up New York Marquee auctions brilliantly with the unprecedented US$1.6 billion Paul Allen sale, coming up next is the 20th/21st Century Art Evening Sale in Hong Kong.

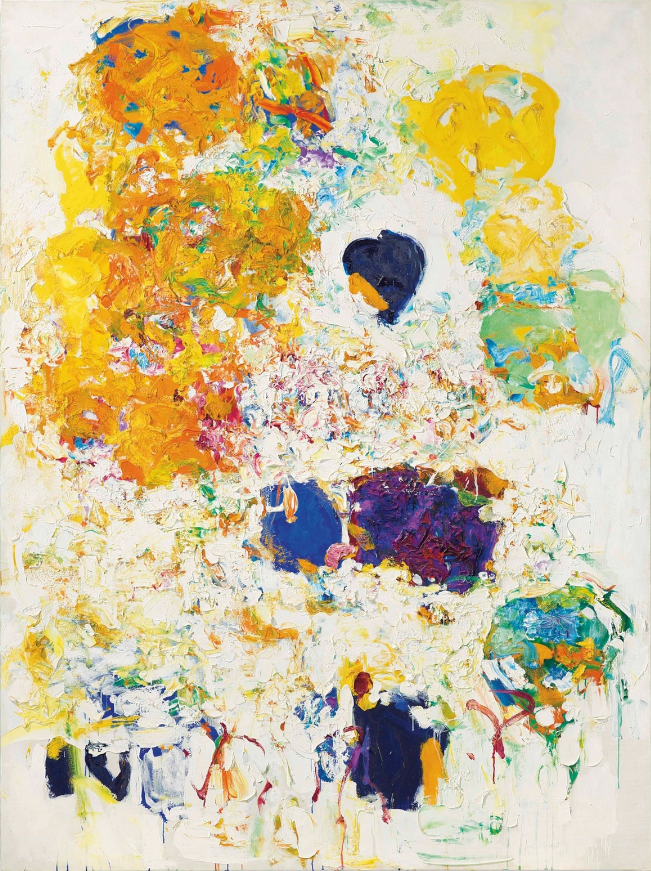

This season, prominent American artist Joan Mitchell’s Untitled will take the lead in the sale, carrying an estimate ranging from HK$80 to 120 million (around US$10.2 – 16.5 milllion). This will be the first time that a painting by the artist to be offered at Christie’s in Asia.

Other highlights include blue-chip artists Sanyu’s 1940s masterpiece Potted Prunus and 10.01.68. from Zao Wou-ki’s highly sought-after Hurricane Period. Combined, they are expected to fetch at least HK$153 million (US$19.6 million).

While the first-in-Asia sale of a Tyrannosaurus rex skeleton has been a talk of the town, the house has decided to withdraw the much-anticipated star lot.

Joan Mitchell (1925-1992). Untitled. Oil on canvas. 278 × 199 cm. (109 1/2 × 78 3/8 in.) Painted in 1966-1967.

At a time when women were underrepresented in the art world, Joan Mitchell was one of the few female artists to attain critical acclaim and commercial success, establishing herself as a key figure among the second generation of Abstract Expressionists.

Born in 1925, Mitchell arrived in New York in 1949 after graduating from the School of the Art Institute of Chicago. Her expansive, dynamic canvases packed with rhythmic counterposed lines had swiftly attracted the attention of the city’s Abstract Expressionist leaders, including Willem de Kooning, Franz Kline and Philip Guston. She drank and debated with them at the Cedar Tavern and The Club, the members-only salon where the artists met for weekly discussions.

Mitchell, however, refused pure abstracts or any other aestheitc labels, instead developing her own artistic vocabulary, known as ‘abstacted landscape’, in which she captured in paint internal topographies of emotion and remembered vistas, as she once said, “I carry my landscapes around with me.”

Despite having amassed massive success in New York by the 1950s, she made the decision to leave the city and relocate to Paris in 1959. By the mid-1960s, weary of Paris and feeling sidelined by the rise of Pop and New Realism on the local art scene, she began to look for a new home in the countryside. With the money Mitchell inherited from her mother following her death in 1966, she purchased a magnificent house in Vétheuil, a small town near Claude Monet’s renowned Giverny Garden.

Since then, the fertile, sun-drenched landscape with a direct view of the Seine had served as a major source of inspiration for the artist, leading her to create numerous pieces to express her heartfelt affection on the land that she would call home for the rest of her life.

Painted between 1966 and 1967, the present canvas sees her signature style developed between New York and Paris, unfurling in formal exuberance and brilliant colours. It was made during her hunt for a country home, and is richly evocative of water, sky and vegetation, seeming to foreshadow the growth and freedom that her new rural setting would bring.

Joan Mitchell. Bluberry, sold for US$16,625,000 at Christie’s New York in 2018.

Joan Mitchell. 12 Hawks at 3 O’Clock, sold for US$20 million by gallery Lévy Gorvy at Art Basel in 2021.

One of the most important artists of the century, Mitchell’s works are housed in major museums around the world, including Whitney Museum of American Art, New York; Tate Collection, London. Recently, the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art and Baltimore Museum of Art has co-organized a comprehensive retrospective for the artist, which is now on view at the Fondation Louis Vuitton until February 2023.

At auctions, Mitchell’s record stood at US$16.6 million, set by her 1969 abstract Blueberry when it sold well beyond an estimate between US$5 and 7 million at Christie’s New York in 2018.

In Hong Kong, her 1962 12 Hawks at 3 O’Clock sold for US$20 million to a private collector by gallery Lévy Gorvy at Art Basel in 2021, showing her appeal to the Asian market.

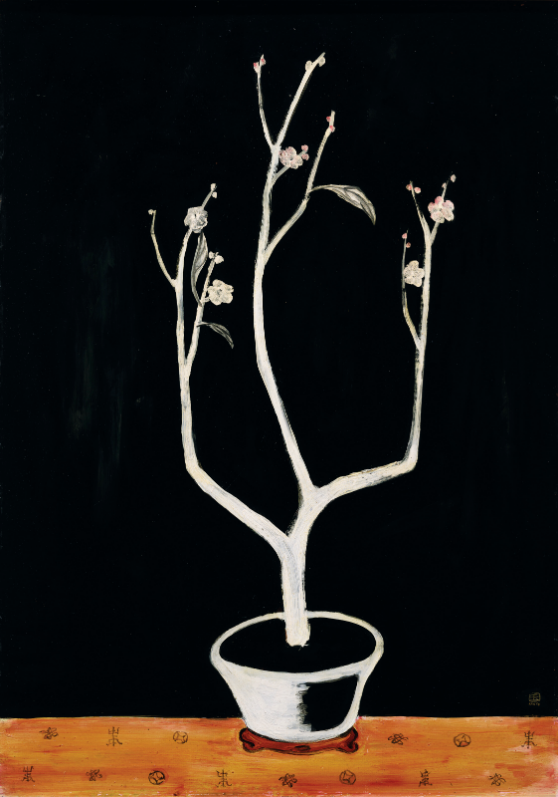

Sanyu (Chang Yu, 1895-1966). Potted Prunus. Oil on masonite. 90.5 × 63.5 cm. (35 5/8 × 25 in.). Painted in the 1940s.

Sanyu is one of bigggest names in the Asian art market in recent years, with his canvases of nudes, flowers and animals generating staggering sums season after season.

In July 2020, his Chrysanthèmes blanches dans un pot bleu et blanc set the auction record for his still-life as it sold for HK$191.6 million (around US$24.4 million) at Christie’s Hong Kong. Three months later, another floral painting, Fleurs dans un pot bleu et blanc, fetched a whopping HK$187,055,000 (US$24.1 million) at Sotheby’s, further cementing his blue-chip status in the market.

While he is hailed as the “Chinese Matisse” today, during his lifetime he lived the life of a miserable artist and remained largely unknown to the art world.

Born in Sichuan during late 19th century, Sanyu was the doted-on youngest child in an affluent family which owned one of the largest silk-weaving mills in the region. As a kid, his love for art was fully supported by his parents, who arranged for him home-school lessons with a skilled calligrapher.

Alongside a wave of young Chinese artists who took advantage of a government-sponsored work-study program, Sanyu arrived in Paris in 1921. When his profound understanding of Eastern art met the thriving Parisian modern art scene, the result were impressive canvases with expressive Chinese calligraphic strokes in strong, vivid colours reminiscent of Fauvism. His talent, however, was unrecognized at the time – instead of exhibitions and sales, he relied on his family’s fortune to support his practice.

In the 1930s when his brother died, his only reliable source of income had also ended. With war ravaging Europe in the years that followed, he only fell into even more dire straits. At his lowest point, he could not even afford to buy art supplies.

Sanyu. Prunus blossoms and Prunus branches. Oil on board. 129×69 cm. Both in the collection of Taiwan’s National Museum of History.

Sanyu. Magpie on a prunus branch. Oil on board. 94×73.5 cm. In the collection of Taiwan’s National Museum of History.

It is in this context the present work was made as the only known Sanyu ‘prunus blossom’ work dating from the 1940s. In Chinese art, plum is referred to one of the four gentlemen, glorified for flourishing into blossoms in the dead of winter. Here, in Potted Prunus, pure, white hues of the blossoms symbolise unwavering perseverance and unsullied elegance, even under the harshest circumstances.

Their subtle fragrance and lonely beauty also allude to the artist’s disposition for his incredible talent and confident self-regard. On the ochre table, Sanyu further painted talismans – symbols of luck, fortune, and longevity.

There are roughly over three-hundred Sanyu’s oil paintings, of which only ten feature prunus blossoms as a subject. Three of them, Prunus Blossoms, Prunus Branches and Magpie on a Prunus Branch, are held in the permanent collection of Taiwan’s National Museum of History, leaving only a handful in private hands.

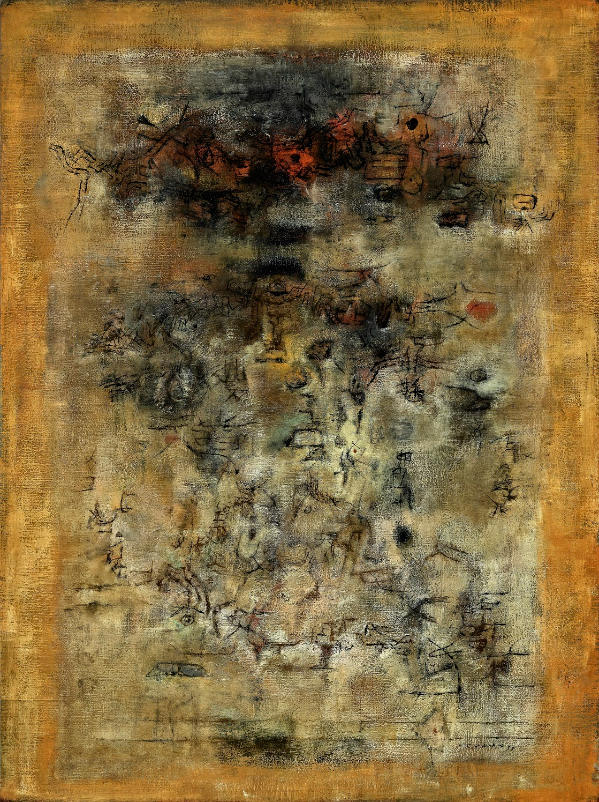

Zao Wou-Ki (Zhao Wuji 1920-2013). 10.01.68. Oil on canvas. 82 × 116.5 cm. (32 1/4 × 45 7/8 in.) Painted in 1968.

Arriving in Paris roughly two decades later than Sanyu, Zao Wou-ki’s life was completely different than his predecessor: not only has he sparked an auction frenzy today, but demands for his works has always been high, and he had constantly received offers to hold solo and abroad exhibitions.

Born in China, he started painting at the age of 10. Much like Sanyu, his early interest in art was encouraged by his family and he was sent to study at the Hangzhou School of Fine Arts. After moving to Paris in 1948, Zao stepped into the field of abstract art. Fascinated by oracle bone texts, he started to compose with rough and bold lines and symbols, resembling seal scripts or ancient glyphs.

In 1957, Zao set out on a year-long trip with Pierre Soulages, travelling to New York, Japan, and Hong Kong. This journey put him at the centre of an international artistic exchange in the post-war era, where he met the leading American Abstract Expressionists for the first time.

Deeply inspired, Zao’s career reached a new pinnacle. In the 1960s, his art entered the Hurricane Period. The oracle bone symbols gradually melted onto his canvas, and the energy and movement of Chinese cursive calligraphy was masterfully blended with Western abstract expressionism, resulting in a bold, powerful and wildly cursive style.

Zao Wou-Ki. Ailleurs. From Zao Wou-Ki’s oracle period.

Zao Wou-Ki. 29.09.64. From Zao Wou-Ki’s hurricane period.

10.01.68 is one of the few known works by Zao from the 1960s that feature two contrasting colours as the main tones. The master had a fondness for orange and azure: From every period of his artistic development starting in the 1940s, there are iconic works that feature tangerine and sky blue as the main colours. The colour orange brings to mind bountiful harvests in autumn, and it is a colour of prosperity and joy.

Blue is not a color rooted in China. Even in the most signature Chinese blue-and-white porcelain, the blue glaze was introduced from West Asia. While for Zao, his blue color palette was inspired by Virgin’s azure blue robe from Europe. In the west, blue, of which pigment was made of Lazurite in Middle Ages, was a noble color, valuable and enduring.

10.1.68‘s performance at auctions has been steady. In 2011, it set a new record high for Zao when it sold for an eyebrow-raising HK$68.98 million (US$8.8 million) at Sotheby’s Hong Kong, smashing his previous record of US$5.9 million. Seven years later, it was offered in the same saleroom once again, and fetched HK$68.93 million.

Some other lots:

Zao Wou-Ki. 12.05.83. Oil on canvas. 130 × 162 cm. (51 1/8 × 63 3/4 in.). Painted in 1983.

Pierre Soulages. Peinture 130×97 cm, 1949.

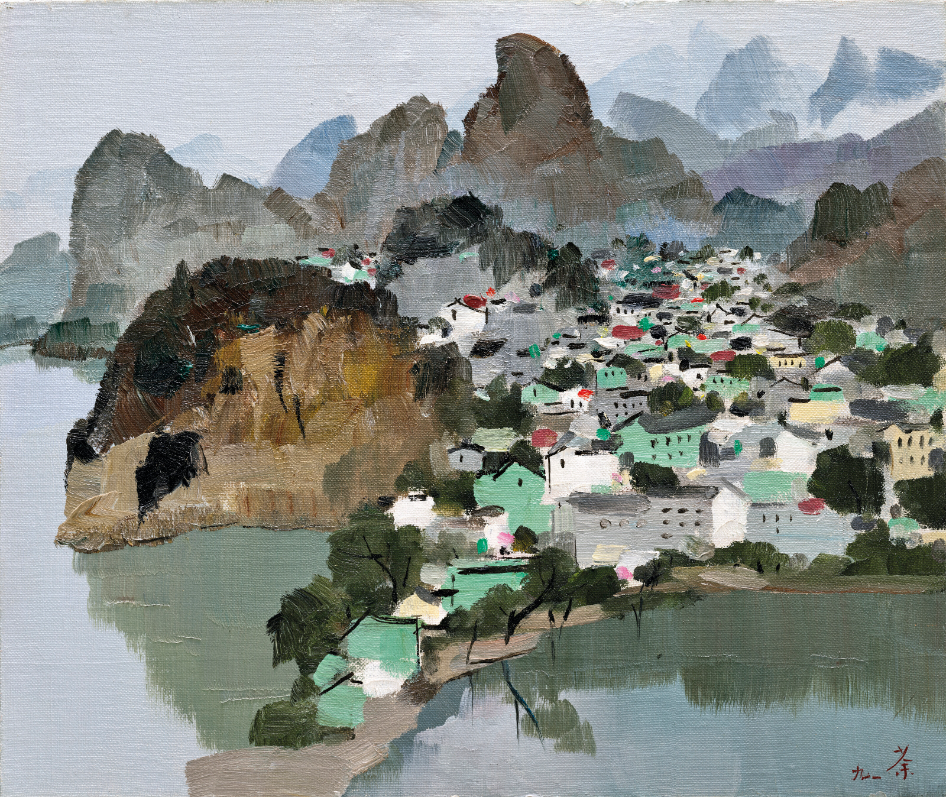

Wu Guanzhong. Guilin. Oil on canvas mounted on board. 46 × 54.7 cm. (18 1/8 × 21 1/2 in.). Painted in 1991.

Source: The Value, Christie’s.