Was Vincent van Gogh ever lucky in love?

The story of Vincent’s love of women is mainly one of setbacks and rejections. There was no shortage of desire or need on his part, but Vincent was never lucky in love. How come it never seemed to work out?

“For my part, I still continually have the most impossible and highly unsuitable love affairs from which, as a rule, I emerge only with shame and disgrace.” — To his sister Willemien from Paris, late October 1887.

EARLY LOVES

As far as we know, the young Vincent proposed to three women: Caroline Haanebeek in 1872, Eugénie Loyer in 1873 and Kee Vos-Stricker in 1881. For a variety of reasons, all three turned him down.

Vincent described what happened with Caroline in a letter to Theo in 1881. “I gave up on a girl and she married someone else, and I went far away from her and kept her in my thoughts anyway. Fatal.” Caroline and her sister Annet, with whom Theo fell in love, were the brothers’ second cousins on their mother’s side. Both stories had a sad ending for the Van Goghs, as Annet fell ill and died, while Caroline married Willem van Stockum.

Vincent was taken on as a trainee in 1873 at Goupil art dealers in London, and so he rented a room in the city. His landlady, Sarah Ursula Loyer, ran a small boys’ school with her daughter Eugénie. Vincent and Eugénie got on ‘like brother and sister’, but things did not go any further: Eugénie, it turned out, was secretly engaged to Samuel Plowman. This time, however, Vincent did not pine for too long: “I’m all right, I’m busy”, he informed Theo.

Vincent met his cousin Kee Stricker while visiting his parents in Etten in 1881. Kee was staying there after the recent death of her husband, and Vincent’s feelings for her ran away with him. He wrote to Theo: “I wanted to tell you that this summer I’ve come to love Kee Vos so much that I could find no other words for it than ‘it’s just as if Kee Vos were the closest person to me and I the closest person to Kee Vos’. And — I said these words to her”. Kee did not see her cousin as husband material, however, answering “No, nay, never” to his repeated proposals.

“Grant that we may meet her on our path, grant that one day Mrs van Gogh sits before us in the carriage. Amen.” — To Theo from Dordrecht, 1877.

LOVE FOR SALE

Vincent was raised in a middle-class home and learned to distinguish between two types of women. Ladies from his own class were viewed as ‘higher beings’, while he felt pity for socially disadvantaged women such as prostitutes. Like his contemporary modern artists, however, it was precisely the latter type of women that he liked to draw and paint.

“It’s not the first time I couldn’t resist that feeling of affection, particularly love and affection for those women whom the clergymen damn so and superciliously despise and condemn from the pulpit.” — To Theo from Etten, around 23 December 1881.

SIEN

In 1882, Vincent rescued Sien Hoornik – a pregnant prostitute with a young daughter – in The Hague. He picked them up from the street and moved them into the little studio where he was living. For a while, Vincent’s longing for a family seemed fulfilled. But things soon began to go wrong and eighteen months later Vincent moved to Drenthe on his own.

“My feelings for her are less passionate than my feelings last year for Kee Vos, but a love like mine for Sien is the only kind I’m capable of (…). She and I are two unfortunates who keep each other company and bear the burden together, and it’s in that way that unhappiness is turned into happiness and the unbearable is made bearable.” — To Theo from The Hague, 1-2 June 1882.

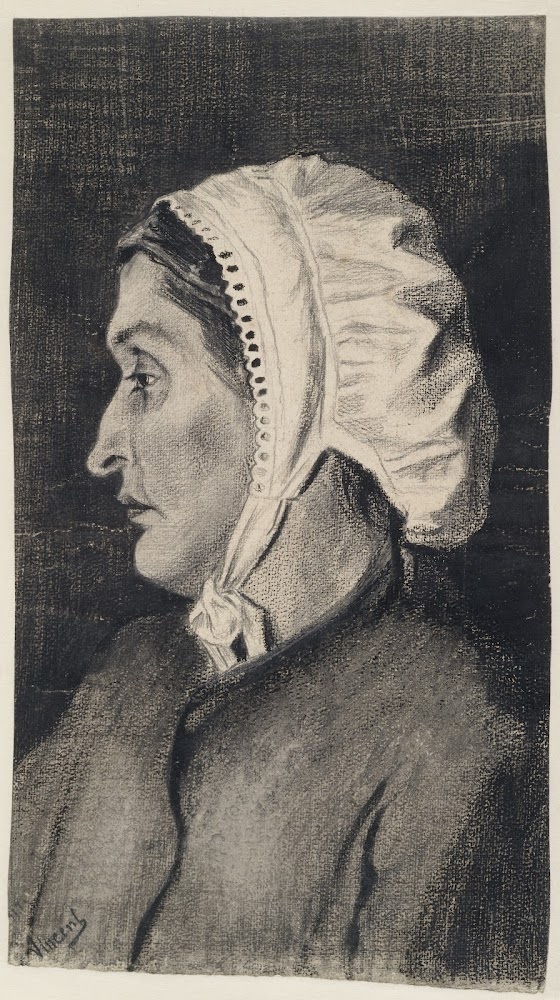

Vincent van Gogh. Head of a Woman. 1882 – 1883.

Vincent, Sien and the children lived together more or less happily for a while following the birth of baby Willem – who was not, as has been suggested, Vincent’s son. But Sien was a difficult character, as was Vincent, and they were constantly short of money. The allowance provided by Theo now had to cover medicine for Sien, rent for Sien’s mother and items for the baby.

Vincent van Gogh. Baby. 1882 – 1883.

Vincent painted this rural couple in a flowering spring orchard in October 1882. There could hardly be a greater contrast with his own life in the bustling city of The Hague and his faltering relationship with Sien. Perhaps he felt the need for an optimistic, ideal image at that particular point.

Vincent van Gogh. Orchard in Blossom with Two Figures: Spring. 1882.

MODELS FROM LIFE

Vincent liked models whom ‘life has given a drubbing’ – a phrase he used when talking about Sien, who also posed for him. Consciously or otherwise, Vincent was opting here for a theme from modern painting, in which prostitutes were used as a symbol of modern (urban) life. Choosing prostitutes as models was largely a practical matter for Vincent – respectable middle-class ladies simply did not want him to paint their portraits.

Vincent van Gogh. Head of a Woman. 1885.

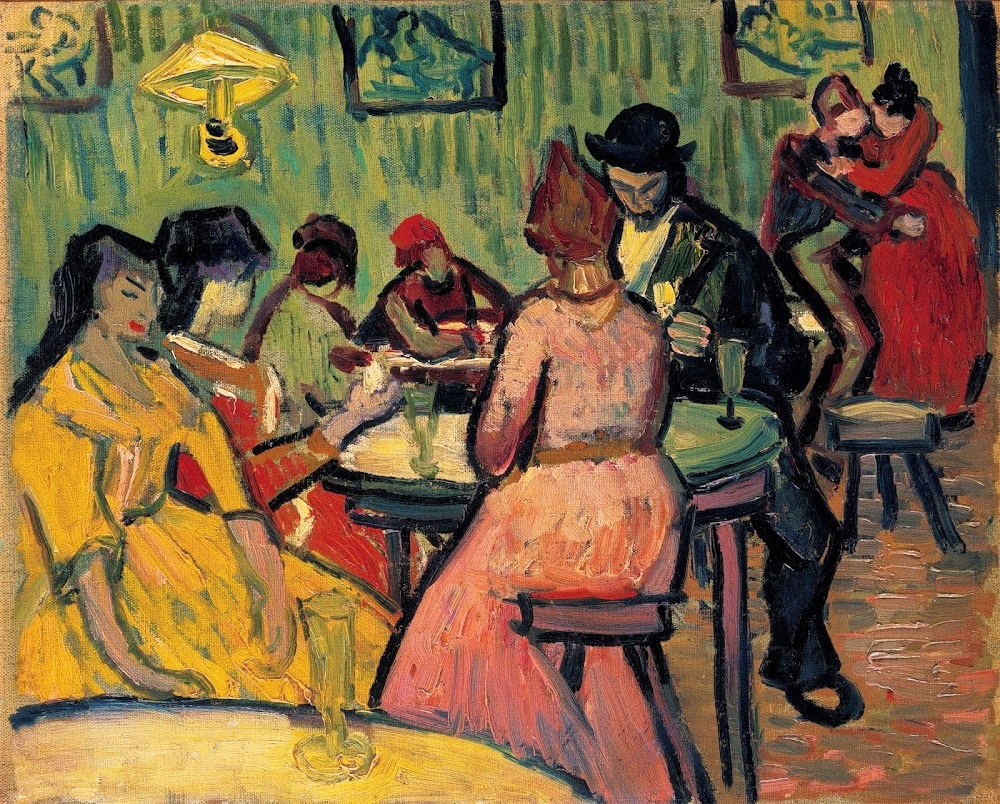

Vincent painted this brothel scene in 1888, during his time in Arles. Paid sex was seen as ‘good for the health’ at the time, and as a normal part of male life.

Vincent van Gogh. The Brothel. 1888. The Barnes Foundation. Merion. Pennsylvania.

Vincent referred to it euphemistically in his letters to Theo, and fairly openly in those to his artist friends. All of them were regular visitors to brothels, which were considered ‘safe’ compared to street prostitution. From time to time, Vincent managed to persuade a woman from the street to pose for him, but few models were prepared to do so entirely nude.

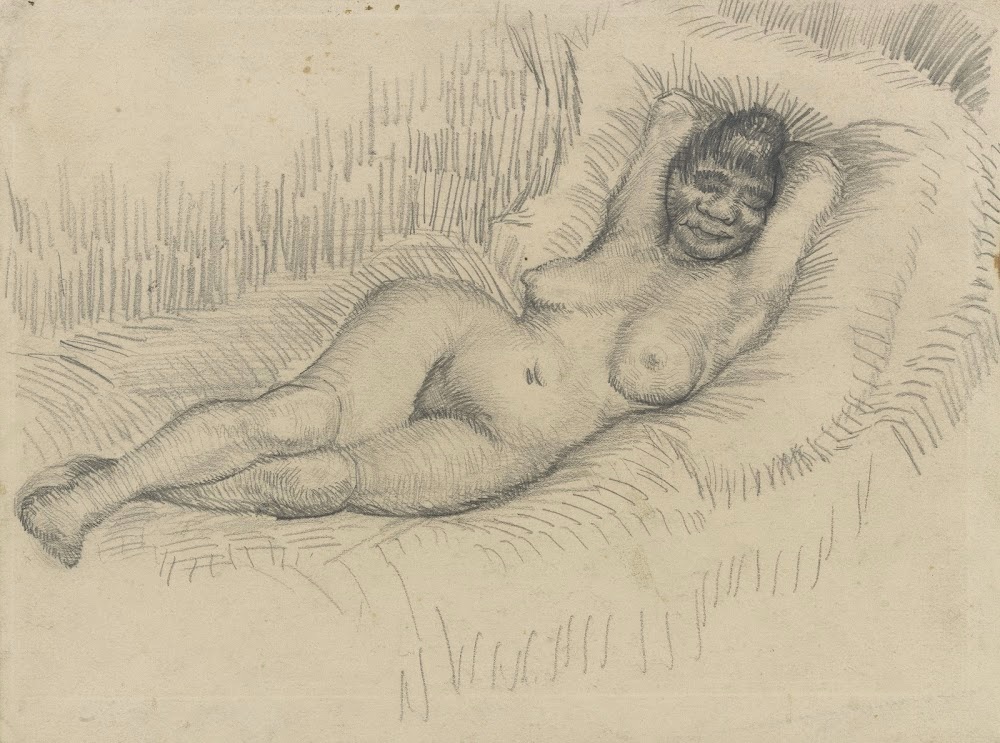

Vincent van Gogh. Study for ‘Reclining Female Nude’. 1887.

This woman – according to Van Gogh’s artist friend Emile Bernard she was a Parisian pierreuse (streetwalker) – was however willing. He made several drawings and paintings of her in a sensual pose, in which he put his newly discovered ‘stripe’ technique into practice.

“Then I thought to myself, I’d like to be with a woman, I can’t live without love, without a woman. I wouldn’t care a fig for life if there wasn’t something infinite, something deep, something real.” — To Theo from Etten, around 23 December 1881.

PROBLEM CHILD

Vincent’s mother and pastor father worried intensely about their son’s troubled love life. They were uncomfortable about the family issues with Kee, let alone Vincent’s plan to marry the working-class Catholic Sien. Even when all that was over, Vincent popped up with another inappropriate candidate, their own neighbour. Vincent’s parents mostly discussed him with Theo, the family mediator, who then briefed his brother on what their mother and father thought of him.

“The business with Margot continues to occupy him very much. We are doing our best to restore him to calm, which is the most important thing. But his outlook on life and his ways are so different from ours, that it’s questionable whether living together in the same place can continue in the long run.” — Father Theodorus van Gogh to Theo, 2 October 1884.

“I am always so worried that wherever Vincent goes and whatever he does he will cut it short everywhere as a result of his odd nature and peculiar ideas and views about life.” — Mother Anna van Gogh to Theo, 7 June 1878.

“It’s no more than natural that you differ in your way of thinking from people who have spent their whole lives in the country and haven’t had the opportunity to partake of modern life, but what the devil made you so childish and so shameless as to contrive in this way to make Pa and Ma’s life miserable and nearly impossible?”— Theo to Vincent, 5 January 1882.

Vincent moved back in with his parents in Nuenen in 1884. Margot, the neighbours’ daughter and ten years his senior, responded to his advances, but their proposed marriage was opposed by Margot’s sisters in particular. The affair ended in dramatic fashion when Margot, distressed by all the gossip, tried to kill herself with rat poison. She survived but the relationship was beyond saving.

Vincent had contact in Nuenen with the farmer’s daughter Gordina de Groot, one of the ‘Potato Eaters’. When Gordina fell pregnant, everyone was positive that that ‘artist fellow’ (schildersmenneke) was involved.

Vincent van Gogh. Head of a Woman (Gordina de Groot). 1885.

Vincent denied it, and it was later shown that he was not the father. Whatever the case, the parish priest lost patience with all the tittle-tattle and promised to pay villagers if they refused to pose for Vincent.

PARIS, CITY OF LOVE

Vincent began to draw in dancehalls and theatres in Antwerp in 1885. Nightlife too had become a new subject in art, and Vincent also painted the faces of prostitutes, which was more modern still. The following year in Paris, he joined up with a group of young artists who painted both the vibrant life of the city and the brothels of Montmartre.

The French artist Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec became virtually synonymous with Paris nightlife. He felt at home in clubs like Le Chat Noir and Le Cirque Fernando, where he depicted a colourful parade of performers: the female clown Cha-U-Kao, the dancer ‘Môme Fromage’, the cancan dancer ‘La Goulue’, the contortionist ‘Valentin le Désossé’ and the Spanish dancer ‘La Macarona’. Vincent met Toulouse-Lautrec through Emile Bernard and the two men became friends.

Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec. Spanish Dancer. 1883 – 1885.

Inspired by his new painter friends, Vincent visited all sorts of entertainment spots, armed with his drawing tools. This open-air café (guinguette) was near the Moulin de Blute-Fin.

Vincent van Gogh, A Guinguette, 1887

It was mostly frequented by couples who came, one contemporary wrote, “to go round in circles on the wooden horses between the jeux divers and the clumps of trees behind which the dining areas were hidden. Whispers interwoven with kisses and laughter. Here, as elsewhere, as everywhere, love is triumphant…”

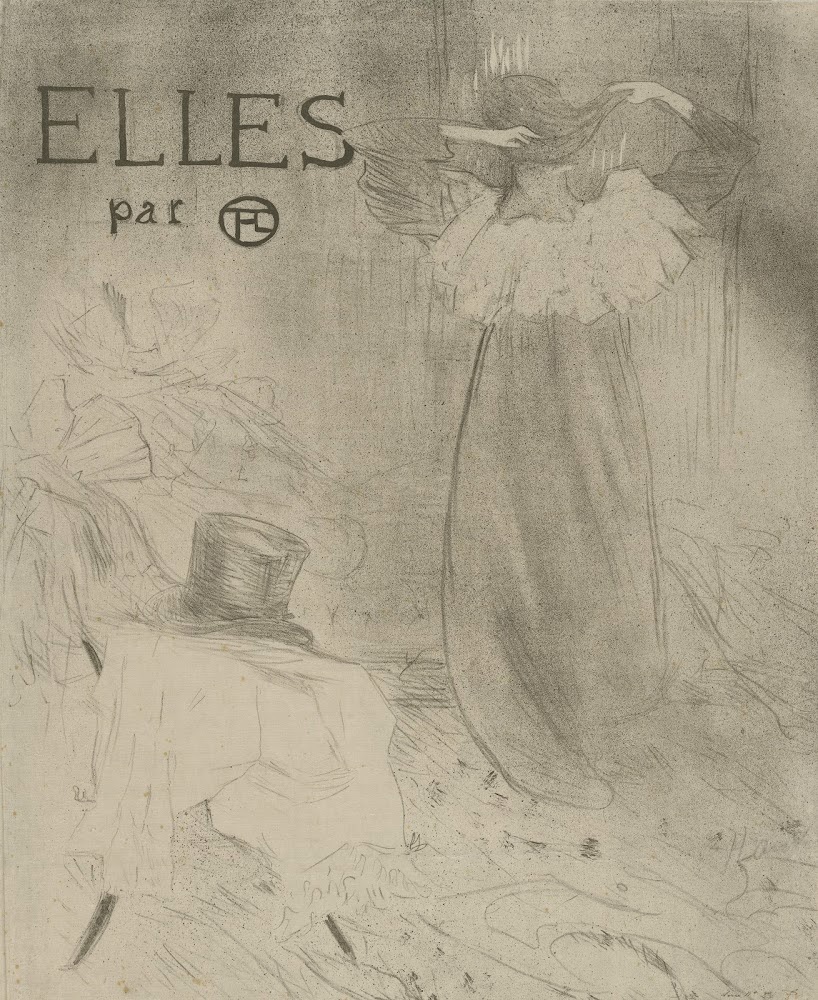

The type of brothels known as maisons closes formed a separate category of Paris nightlife, to which Vincent was introduced by Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec.

Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec. Series Elles. 1896.

Toulouse-Lautrec himself later produced a series of lithographs on the subject. This print of a woman fixing her hair with a man’s hat lying suggestively on the bed was used for the cover. Toulouse-Lautrec displayed the series in two locked rooms – a gallery to which only he had the key, making it as discreet as the subject itself.

AGOSTINA SEGATORI

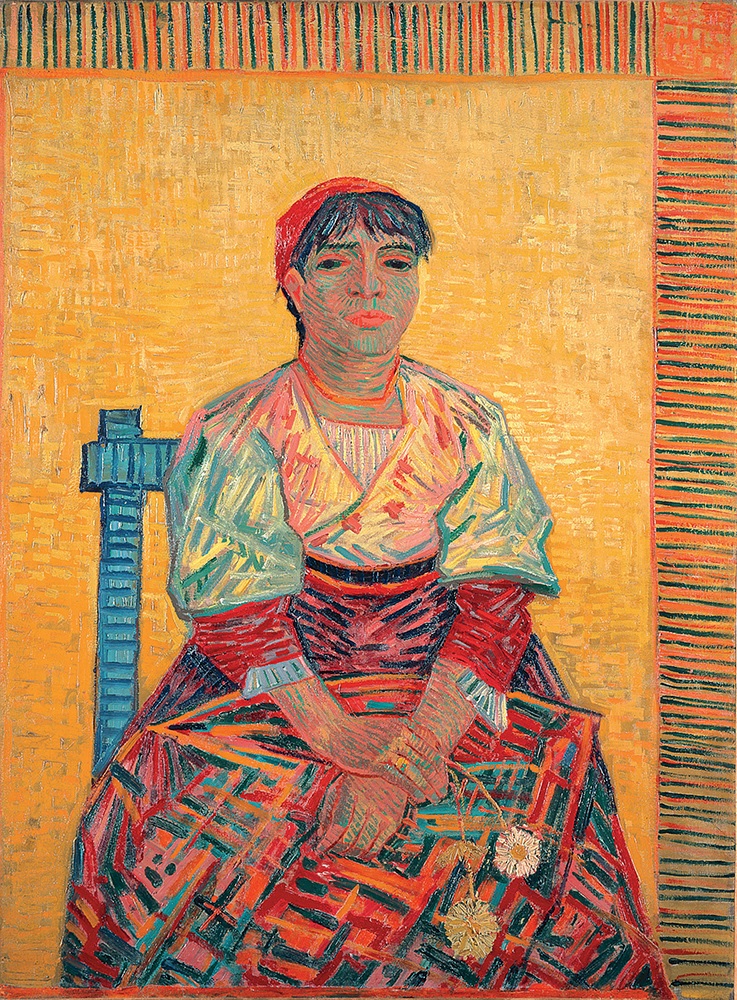

What precisely went on between Vincent and Agostina Segatori, the Italian owner of the restaurant Le Tambourin, on the Boulevard de Clichy, remains unclear. The two had a relationship from December 1886 to May 1887. According to Paul Gauguin, Vincent was ‘very much in love’ with Agostina, but this lady friend too turned out to be a source of problems.

Vincent shows Agostina in this portrait at one of the ‘tambourine’ tables to which her café owed its name. The establishment was popular among artists, who could also exhibit their work there. Vincent was one of them.

Vincent van Gogh. In the Café: Agostina Segatori in Le Tambourin. 1887.

Bernard later claimed that Agostina provided Vincent with free meals in exchange for paintings – mostly floral still lifes.

“As far as Miss Segatori is concerned, that’s another matter altogether,” Vincent wrote to Theo in 1887.

The Italian Woman (Agostina Segatori), 1887, Musée d’Orsay, Paris.

“I still feel affection for her and I hope she still feels some for me. But now she’s in an awkward position, she’s neither free nor mistress in her own house, and most of all, she’s sick and ill.”

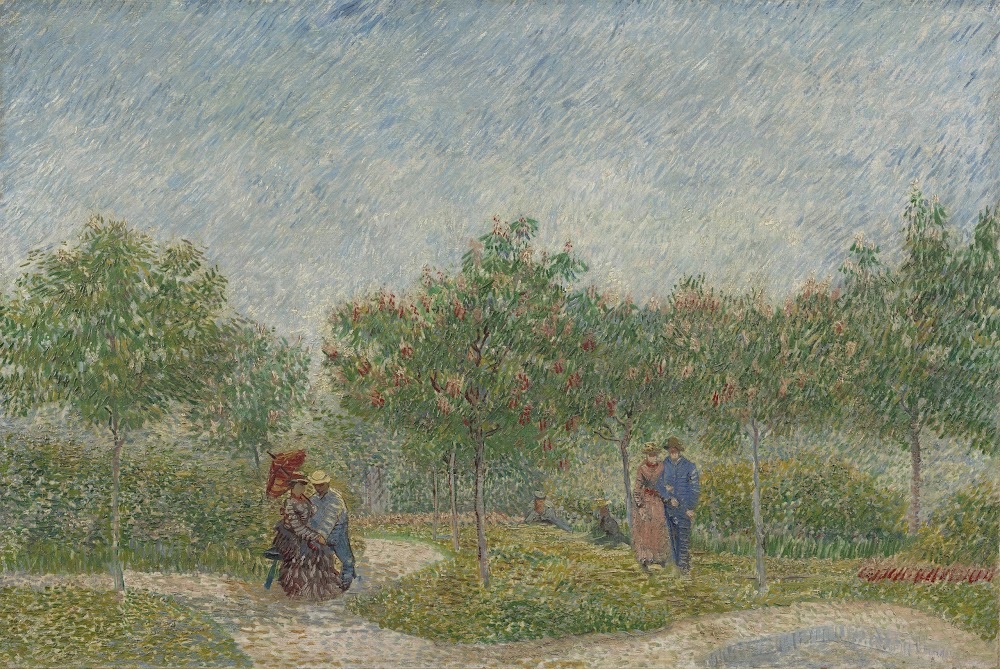

Vincent must have been very fond of Agostina Segatori. He made several paintings of courting couples in the period in which they were seeing each other.

Vincent van Gogh. Garden with Courting Couples: Square Saint-Pierre, 1887.

The most famous of these is the Garden with Courting Couples – a romantic vision of the little park at Square Saint-Pierre. Could it be that Vincent painted himself here – in a blue smock and straw hat – next to the woman with the parasol?

ACCEPTANCE

After so many failed relationships, Vincent eventually came to accept his fate. His unpredictable, maladjusted and unstable personality proved entirely unsuitable when it came to matters of the heart.

In Arles in 1888, Vincent turned to prostitutes for comfort and to his ‘requited loves’ – art, nature and his brother Theo.

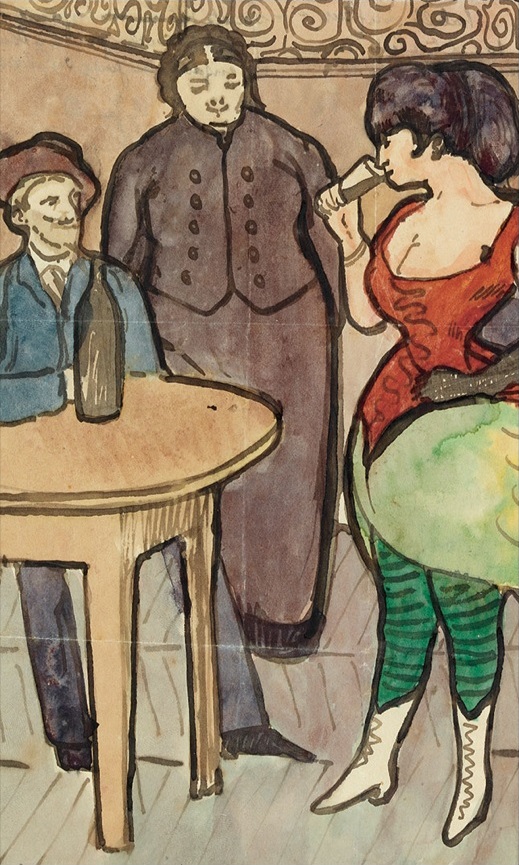

Vincent could speak freely about his brothel visits to his friend Émile Bernard. The younger painter also immersed himself artistically in the subject.

Émile Bernard. Brothel scene. 1888, Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam.

He owned the two nude paintings that Vincent had made of the Paris ‘streetwalker’, and it was around the same time that Bernard produced the series of watercolour drawings In the Brothel. He sent one of them to Arles, “For my friend Vincent, this silly sketch”.

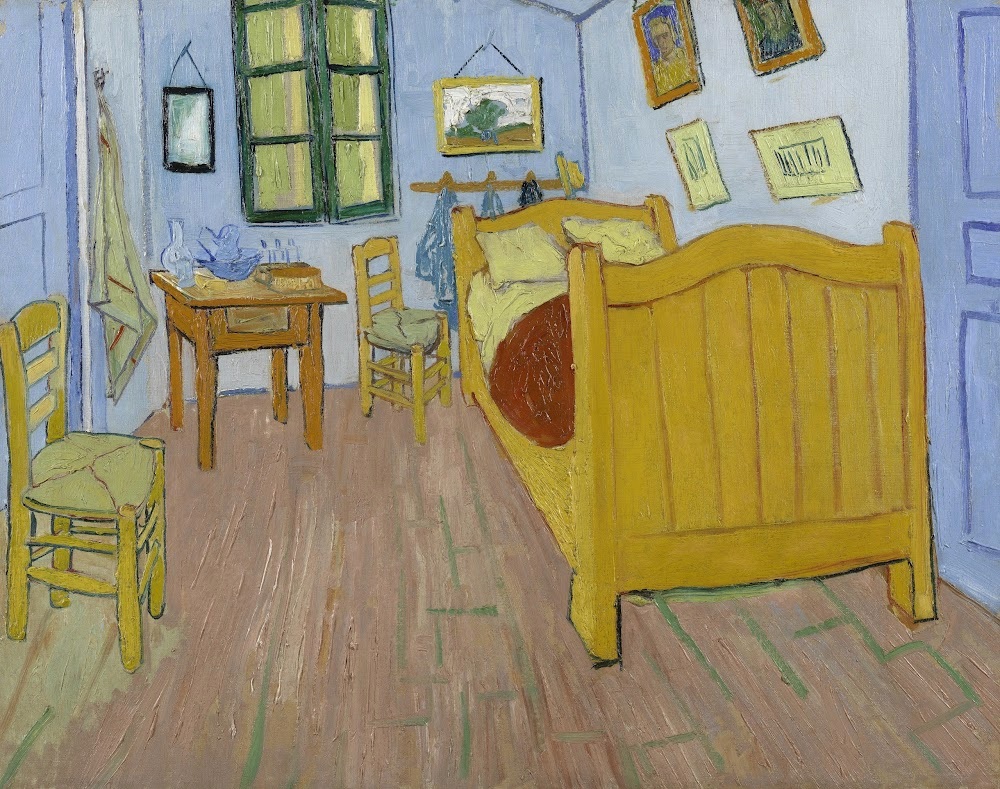

Vincent painted his Bedroom in the summer of 1888. Revealingly, he placed two pillows on his single bed. He had already written years earlier that “If you wake up in the morning and you’re not alone and you see in the twilight a fellow human being, it makes the world so much more agreeable.” He accepted in Arles that there would never again be such a fellow human being for him. He made up for it by seeking affection outside his bedroom.

Vincent van Gogh. The Bedroom. 1888.

Vincent oscillated throughout his life between his respect for women as chaste, unattainable creatures and his need for intimacy and sex. The same struggle might also have contributed to his mental breakdown in Arles.

Emile Schuffenecker, copy after Vincent’s Self-Portrait with Bandaged Ear, 1892-1900, Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam.

“I believe that certainly it’s better to bring up children than to expend all one’s nervous energy in making paintings, but what can you do, I myself am now, at least I feel I am, too old to retrace my steps or to desire something else. This desire has left me, although the moral pain of it remains.” — To Theo and Jo from Auvers-sur-Oise, ca. 10 July 1890.

Source: Van Gogh Museum