Alastair Smart takes a deep dive into the life of Impressionism’s founding father, illustrated with masterpieces previously sold in Christie’s Impressionist & Modern Art sales and those offered in upcoming auctions

1, His childhood drawings gained notoriety

Oscar-Claude Monet was born in Paris in November 1840. At the age of five he moved with his family to the town of Le Havre, in Normandy, where his father ran a grocery business. He became notorious at school for drawing caricatures of his teachers; that notoriety soon spread throughout Le Havre when he started caricaturing well-known citizens — and displaying the results of his efforts every Sunday in the window of a local framemaker’s shop.

2, As a student in Paris, he shared quarters with Pierre-Auguste Renoir

Seeking to pursue a career as an artist, Monet returned to Paris and joined the atelier of Swiss master Charles Gleyre. Times were tough, and as a young man he led a bohemian existence. He shared quarters with his classmate, Pierre-Auguste Renoir, and they survived on a diet of pulses. The pair devised a routine that involved cooking just before a model arrived to pose in the nude — since, for heating purposes, the stove would have to be lit anyway.

3, Despite his criticism of the Paris Salon, his 1865 submissions were a hit

Monet was intensely critical of the Paris Salon (the official, annual art exhibition sponsored by the French government), which he regarded as stuffy and anti-progressive. But to pacify his Aunt Marie-Jeanne, who was somewhat reluctantly funding his art studies, he submitted two seascapes in 1865. La Pointe de La Hève at Low Tide and Mouth of the Seine at Honfleur were both hits. The critic of the Gazette des Beaux Arts magazine wrote that ‘a new name in art must be mentioned. Monsieur Monet’s daring way of seeing and enforcing our attention… are advantages he possesses in the utmost degree.’

Claude Monet (1840-1926), La route de Vétheuil, effet de neige, 1879. Oil on canvas. 24⅛ x 32⅛ in (61.1 x 81.1 cm). Sold for $11,447,500 on 15 May 2017 at Christie’s in New York

4, Monet suffered through all weathers for his art

Monet was a firm believer that art should be vital, immediate and directly inspired by nature — which meant the radical step of painting outdoors — en plein air — rather than in a studio. This would become a key tenet of Impressionism (made possible by the invention in 1841 of readymade oil paint in portable, metal tubes). Anecdotes exist of Monet heading out in sub-zero temperatures, wearing three coats, with a hot water bottle for his feet and icicles on his beard.

‘It was cold enough to split rocks,’ wrote one journalist after a winter encounter with Monet. ‘We perceived a foot warmer, then an easel, then a gentleman bundled up, in three overcoats, gloves on his hands, his face half frozen; it was Monet studying an effect of snow.’

In the summer of 1869, Monet, Pissarro, and Sisley descended on the towns of Louveciennes and Bougival in the Seine valley to the west of Paris. For the next year — in one of the greatest collaborative experiments in the history of art — they worked together to hone their shared plein-air language. In the work shown above, Monet opted to paint the unassuming suburban landscape on a snowy day under a fiery sunset sky.

5, He was a committed Anglophile

In 1870, as France and Prussia went to war, Monet headed for the safety of London. He would make repeated visits across the Channel during his lifetime, regularly dining with English aristocrats and developing a love of tea and tweed. He also enjoyed visits to the National Gallery, where he studied the landscapes of Constable and the seascapes of Turner.

Claude Monet (1840-1926), Le Parlement, soleil couchant (The Houses of Parliament, at Sunset), 1902. Oil on canvas. 32 x 36⅝ in (81.3 x 93 cm). Sold for $40,485,000 on 11 May 2015 at Christie’s in New York

In his letters, Monet expressed his enchantment with the English weather. In February 1901, he exclaimed: ‘There is no country more extraordinary [than this one] for a painter!’ Still, on account of the volatility of London’s weather, Monet was often forced to complete his London canvases at Giverny, where he reworked and completed them in his studio.

6, Monet never tired of painting the Seine — for him, it was ‘always new’

Monet was fascinated by the Thames, particularly on days when coal smoke produced spectacular, colour-filled fog above the water. When in London he’d book himself into the Grand Suite at the Savoy Hotel, to ensure an optimal view of the river.

Still more significant for Monet was the Seine, which he painted over and over again. ‘I have painted the Seine throughout my life, at every hour, at every season,’ Monet said. ‘I have never tired of it: for me the Seine is always new.’ Monet’s views of the Seine allowed him to explore themes, such as the effect of light, that were central to his work.

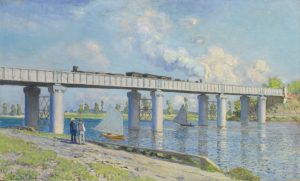

Claude Monet (1840-1926), Le Pont du chemin de fer à Argenteuil, 1873. Oil on canvas. 23⅝ x 38¾ in (60 x 98.4 cm). Sold for $41,480,000 on 6 May 2008 at Christie’s in New York

The Seine-side enclave of Argenteuil is synonymous today with the origins of Impressionism. When Monet moved to Argenteuil, it was a lively suburb just 11 kilometres west of the capital. As other progressive painters — including Manet, Renoir, Sisley, and Caillebotte — joined him, the town became the centre of the New Painting, which dared to subvert long-standing Salon norms.

Although Monet explored a wide range of motifs at Argenteuil, it was the river that provided him with the greatest source of inspiration. Between 1872 and 1875, he created more than 50 paintings of this stretch of the Seine.

7, The Impressionists were originally known as the ‘Anonymous Society’

Like his friends Renoir, Sisley and Degas, Monet opposed the stranglehold that the Salon held over artists. In response, in 1874 the group set up the Anonymous Society of Painters, Sculptors and Engravers, a co-operative through which artists could exhibit independently. Sales were poor, as was attendance, but it was nevertheless a landmark event. Monet showed five oil paintings, including one called Impression: Sunrise, a view of Le Havre in which he tried to capture the fugitive, dawn light. One hostile reviewer of the show, Louis Leroy, picking up on Monet’s title, branded all its artists mere ‘Impressionists’. The name would stick, but soon lost the negative connotation.

8, Monet had the power to interfere with railway schedules

The Impressionists heeded the call of writers such as Émile Zola and Charles Baudelaire to paint modern subjects. Paris was transformed in the mid-19th century, its cramped and crooked, medieval lanes making way for sweeping, new boulevards. Railway travel also boomed — and Monet was particularly impressed by the visual effects of the steam engine. On more than one occasion, he is known to have persuaded the station master at Gare Sainte-Lazare to delay a train’s departure in his bid to capture the perfect picture.

Claude Monet (1840-1926), Extérieur de la gare Saint-Lazare, effet de soleil, painted in Paris, 1877. 24⅛ x 31¾ in (61.3 x 80.7 cm). Sold for $32,937,500 on 8 May 2018 at Christie’s in New York

9, After moving to Giverny, he announced ‘I’m good for nothing now except painting and gardening’

In 1883, opting for a more sedate life, Monet moved with his family to the village of Giverny, 50 miles west of Paris. He employed six gardeners for his sizeable grounds, but wasn’t averse to tilling his own fair share of soil. Peonies and red geraniums jostled for attention with pansies and yellow roses.

Claude Monet (1840-1926), Le pont japonais, painted in Giverny, circa 1918-1924. 28¾ x 39½ in (73 x 100.3 cm). Estimate: $12,000,000-18,000,000. Offered in Impressionist and Modern Art Evening Sale on 13 May 2019 at Christie’s in New York

After his return from a three-month painting trip on the Italian Riviera in April 1884, Monet had made the rich landscape around his Giverny home almost the sole subject of his art. ‘If I am happy to work in this beautiful area,’ the artist wrote while abroad, ‘my heart is always in Giverny.’

Claude Monet (1840-1926), Coin du bassin aux nymphéas, painted in Giverny, circa 1918-1919. 51⅜ x 35 in (130.5 x 88.8 cm). Estimate: $15,000,000-25,000,000. Offered in Impressionist and Modern Art Evening Sale on 13 May 2019 at Christie’s in New York

His most famous horticultural feat, though, was creating an entire water garden, in which a Japanese-style bridge traversed a large lily pond, surrounded by willow trees. Monet would go on to paint his jardin d’eau around 250 times.

Claude Monet (1840-1926), Nymphéas en fleur, painted circa 1914-1917. 63 x 70⅞ in (160.3 x 180 cm). Sold for $84,687,500 on 8 May 2018 at Christie’s in New York

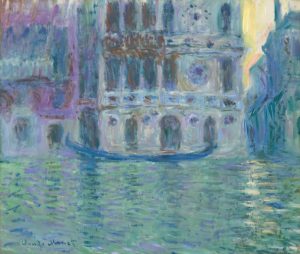

In September 1908, Monet and his wife Alice received an unexpected invitation to visit Venice. The 68-year-old artist had scarcely strayed from Giverny since his London campaigns at the turn of the century, so utterly absorbed was he in his Nymphéas series.

At Giverny, Monet had narrowed his vision to comprise only the tilted plane of the water garden, with nothing more firm to paint than the floating lily pads. Venice provided an invigorating alternative to this condensed repertoire, offering the artist a dance of light over the architecture as well as the surface of the water with its fractured reflections.

Claude Monet (1840-1926), Le Palais Dario, painted in Venice, 1908. 22⅛ x 26⅛ in (56.2 x 66.5 cm). Estimate: $4,000,000-6,000,000. Offered in Impressionist and Modern Art Evening Sale on 13 May 2019 at Christie’s in New York

10, As Paul Cézanne said, ‘Monet is only an eye. But what an eye!’

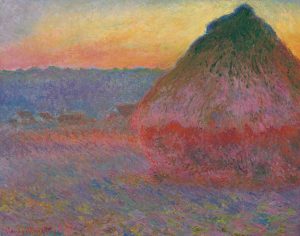

Executed in the winter of 1890-91, Monet’s grainstack paintings were the most challenging the artist had undertaken. Each of the works in the series — some 25 canvases in all — were differentiated almost entirely through colour, touch and atmospheric effect.

Setting up his easel in his garden in Giverny, Monet looked west or southwest toward the hills on the far bank of the Seine. There, after the harvest, farmers piled sheaves of wheat stalks into tightly packed stacks with thatched, conical roofs. These grainstacks represented the fruits of the farmers’ labours, and their hopes for the future.

In May 1891, Monet and his art dealer Durand-Ruel exhibited 15 Meules to great acclaim. By year’s end, all but two paintings from the series had left the artist’s studio. In November 2016, the world auction record for a work by Monet was set at Christie’s in New York when Meule (1891) sold for $81,447,500. This was surpassed in May 2018 when Nymphéas en fleur from the Collection of Peggy and David Rockefeller realised $84,687,500.

Claude Monet (1840-1926), Meule, 1891. Oil on canvas, 28⅝ x 36¼ in (72.7 x 92.1 cm). Sold for $81,447,500 on 16 November 2016 at Christie’s in New York

With these paintings, Monet sought to capture the flood of multi-coloured daylight as visionary experience. Monet explained the challenge to his friend, the art critic Gustave Geffroy, in October 1890: ‘The further I go, the more I see that a lot of work is needed to get at what I am looking for: instantaneity, above all the envelope, the same light suffused everywhere.’ It was Monet’s obsession with reproducing the scintillating play of light that prompted Paul Cézanne’s comment: ‘Monet is only an eye. But what an eye!’

11, He lost two wives, a son and — eventually — his eyesight

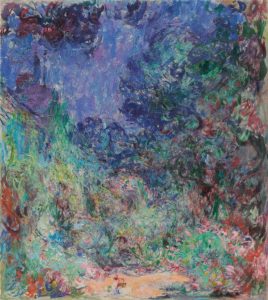

Monet’s first wife, Camille, died in 1879 at the age of 32; his second, Alice, passed away in 1911. His son, Jean, died in 1914. Around this time, Monet was diagnosed with double cataracts. Many observers use his impaired vision as an explanation for the increasingly abstract forms Monet painted late in his career; the thickening layers of paint he applied; and his growing fondness for unnatural colours.

Claude Monet (1840-1926), La maison vue du jardin aux roses, painted in Giverny, circa 1922-1924. 39½ x 35⅛ in (100.4 x 89.3 cm). Estimate: $4,000,000-6,000,000. Offered in Impressionist and Modern Art Evening Sale on 13 May 2019 at Christie’s in New York

12, Monet’s grandest paintings — his ‘monument to peace’ — were intended as a gift to his homeland

On 12 November 1918, the day after the signature of the Armistice that ended the First World War, Monet vowed to create a ‘monument to peace’. This consisted of a set of giant water-lily paintings (each two metres high) dedicated to the French nation. Prime Minister Georges Clemenceau agreed that these would go on display in the Orangerie, in Paris’s Tuileries Gardens. Eight were installed at the Orangerie shortly after his death (in 1926, aged 86, of pulmonary sclerosis) — where they still hang today.

13, In his final paintings, Monet broke with the standards of Impressionism

The artist who as a young Impressionist espoused spontaneity to capture the fleeting effects of light and colour, would in these final paintings subject nature to sustained contemplation. Perhaps more significantly, if in early Impressionism the artist’s vantage point was stable and clearly defined, the water lilies reflected a move to a much more immersive style.

In these paintings, traditional markers such as a bridge or the horizon have been erased. Just as Cubism was challenging traditional notions of the figure in space, Monet’s late work presented a radical rethink of perspective.

Source: Christie’s