As a new series of exhibitions marks 50 years since Picasso’s death, critic Ben Luke talks to the artist’s grandson about how his legacy is being considered afresh.

When Pablo Picasso died on 8 April 1973, it was clear that the world had lost a titanic cultural figure. In the New York Times’ frontpage story the next day, Alfred Barr, the founding director of New York’s Museum of Modern Art, said: “We are fortunate in having been witness to his presence in our time.”

For Olivier Widmaier Picasso, then a teenager in Paris, it was life-changing. He found out about his grandfather’s death through a TV newsflash. “And it was a shock, because you don’t normally receive this kind of [personal] information on television. For me, Pablo Picasso was just the father of my mother.”

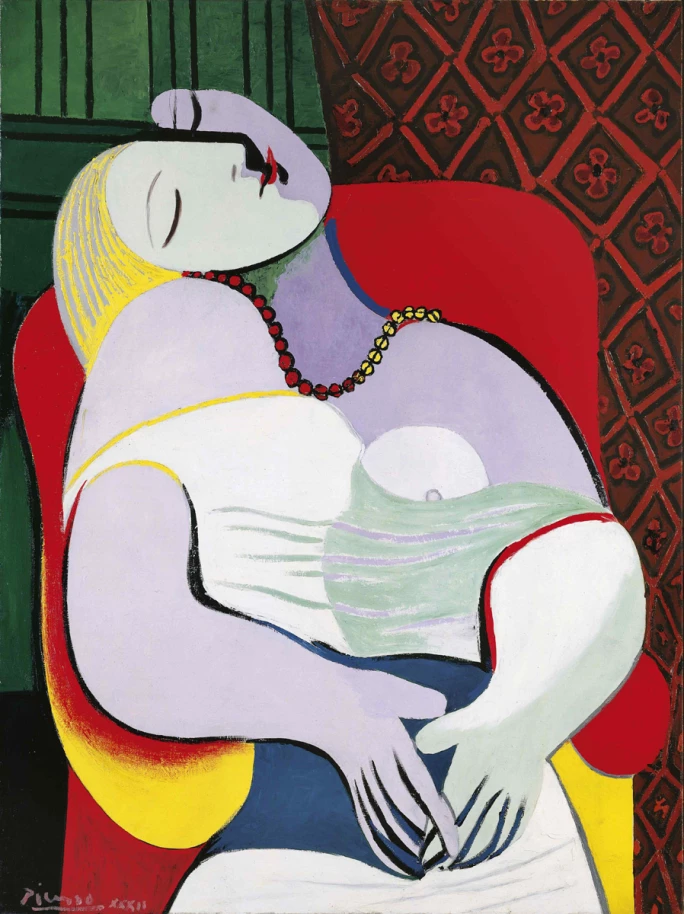

Pablo Picasso. Le Rêve (The Dream). 1932. Depicting then-mistress Marie-Thérèse Walter. Photo: © Succession Picasso/Dacs, London 2022, Alamy.

Widmaier Picasso was born in 1961, the son of Maya Picasso – daughter of the artist with his mistress and muse Marie-Thérèse Walter – and Pierre Widmaier, a former navy officer. Walter, a model, became the subject of some of Picasso’s most famous portraits, not least among them the erotic Le Rêve (The Dream), 1932, and Girl before a Mirror, from the same year. But before the great artist’s death, Widmaier Picasso had been sheltered from his fame. “We had paintings, drawings, some pictures at home, but he was somebody that I didn’t see, because he was living quite far away,” he says. In the days following Picasso’s death, he explains, “I discovered someone much bigger than I thought; much more important.”

The fiftieth anniversary of Picasso’s death is being marked by more than forty exhibitions in Europe and the US, brought together under Celebration Picasso 1973–2023. The exhibitions reflect how broadly the life and work of Picasso can still be explored and interpreted, analysing everything from the Old Masters’ influence on him and particular periods of his work, to his relationship with his contemporaries and responses by artists today. There are sixteen shows in Picasso’s native Spain alone, and twelve in his adopted home of France. “People ask, ‘Was he Spanish, was he French?’” says Widmaier Picasso. “And I say, Pablo was Spanish, but Picasso was French. And today, he’s more than that: he’s a citizen of the world.”

Pablo Picasso. Girl before a mirror. 1932. Oil on canvas. 162.3 cm × 130.2 cm (63.9 in × 51.3 in).

Widmaier Picasso, a businessman and TV producer, says he came to realise that Maya “was the one [of Picasso’s children] that probably spent the most time with Picasso. When she was a child, as a teenager and even as a young adult, she was close to her father. She had become a kind of confidante.” One of the most famous stories relating to Maya – who is now 87-years-old – involves her encounter with Picasso’s Guernica as he painted it in a Paris studio in 1937. “It’s quite magical,” Widmaier Picasso says. “The little memories she has about it – that she put her finger on the huge canvas, probably leaving a fingerprint – add to the message of the painting. It’s the innocence of children killed by the attack on Guernica, and a child who is looking at the beautiful painting, recognising the face of Marie-Thérèse there, and touching it with the same kind of innocence.” Maya took Olivier there many years later; a “really touching” experience for him. He also fondly recalls his time with Marie-Thérèse Walter, who died by suicide in 1977. “She was a loving person, and she barely referred to Picasso, but [when she did, it was] with nice memories. Nothing was complicated.”

Pablo Picasso. Guernica. 1937. Oil on canvas. Dimensions: 349,3 × 776,6 cm.

Many have commented on Picasso’s extraordinary ability to capture the essence of his sitters, even when he fragments and distorts their faces and bodies. Picasso famously said in response to criticisms of his portrait of Gertrude Stein (a relationship that is the subject of an exhibition at the Musée du Luxembourg, Paris, in September 2023) that: “Everybody thinks she is not at all like her portrait, but never mind, in the end she will manage to look just like it.” Does Widmaier Picasso feel that a similar perceptiveness is required to truly understand the portraits of his grandmother? “Oh, yes. I think that you have to train your eyes like you have to train your ear when you go to the opera,” he says. He adds, however, that as he grew more familiar with his grandfather’s work, “it became more and more obvious that Picasso was seeing people, objects and landscapes with more intensity. And, for sure, he was able to draw the face of Marie-Thérèse to the perfection of a classical drawing. But at the same time, he was symbolising not only the physical aspect of her – the beautiful curves – but also her consciousness, or their love, through the simplification of what we can call Surrealism. By the time I got more used to seeing those paintings, I instantly got the relationship.”

Pablo Picasso. Gertrude Stein. 1905–6. Oil on canvas. 39 3/8 × 32 in. (100 × 81.3 cm).

At the time that Picasso died, there was much debate about his late work, which will be the subject of two 2023 shows: at the Beyeler Foundation, Basel, and La Casa Encendida, Madrid. Even long-term supporters dismissed it; the collector and scholar Douglas Cooper described “only incoherent doodles done by a frenetic dotard in the anteroom of death”. But, Widmaier Picasso says, “It took time for people to understand that it was probably the last attempt of a genius to show he still had something to say.” He believes the late works will grow in importance and that “in their size, the intensity of paint”, they connect with the Neo-Expressionist painting of the late 1970s and 1980s “and especially with Jean-Michel Basquiat”.

Pablo Picasso. Le Moulin de la Galette. Paris, ca. November 1900. Oil on canvas. 35 5/16 inches × 46 inches (89.7 × 116.8 cm).

Other highlights of Celebration Picasso 1973-2023 include the Picasso – El Greco exhibition at the Prado in Madrid in June, an adaptation of a show recently put on at Kunstmuseum Basel that zones in on the connections between the two artists. “To me, it’s emotionally touching to think that my grandfather visited the Prado museum to get inspired by Goya, El Greco and Velázquez and, more than a century later, [that has inspired] an exhibition in Madrid.” The Guggenheim Museum in New York is focusing on Picasso’s very first Parisian picture, Le Moulin de la Galette, 1900, capturing a scene in the notorious Paris dance hall, which “will be very important for people to understand how it all started,” says Widmaier Picasso.

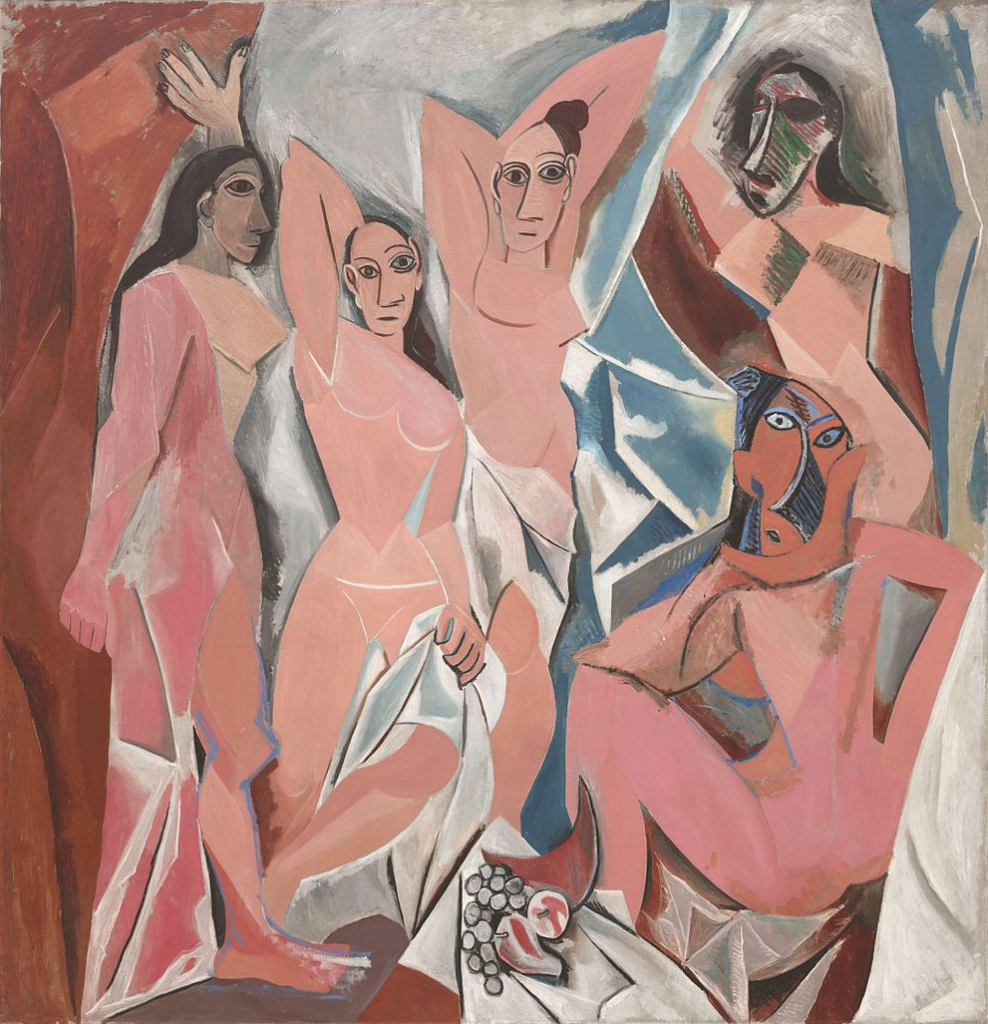

Pablo Picasso. Les Demoiselles d’Avignon. 1907. Oil on canvas. 243.9 cm × 233.7 cm (96 in × 92 in).

The Daniel-Henry Kahnweiler exhibition at Museu Picasso in Barcelona, until March 2023, looks at Picasso’s influential dealer, who saw Les Demoiselles d’Avignon, 1907, in Picasso’s Montmartre studio – “but nobody else understood it at that time. So this man was so important at the beginning.” From March, meanwhile, the Musée Picasso-Paris will present a new configuration of its collection, conceived by fashion designer Paul Smith, which Widmaier Picasso expects to be an “innovative way” to show “all the masterpieces of the museum”. A remarkable exhibit of Picasso’s works on paper opens at the Centre Pompidou, Paris, in October; Picasso: 2023 drawings will feature 2,023 drawings and prints, from tens of thousands of examples across Picasso’s life – a “profusion of drawing and engraving,” he says. He also points to “something very special” at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York in September, focusing on Picasso’s unrealised commission during his Cubist years for the library of a Brooklyn townhouse belonging to critic and collector Hamilton Easter Field. “It’s a novel way to consider Picasso; I didn’t know that he once tried to be an interior designer.”

Among the most intriguing exhibitions (yet to be titled), will be at the Brooklyn Museum in June, co-curated by the comedian Hannah Gadsby, who said in her Netflix show Nanette: “I hate Picasso […] Picasso suffered the mental illness of misogyny.” Widmaier Picasso believes it is “very important nowadays, after the #MeToo movement, to explore this question with Picasso. It’s absolutely necessary to have a real knowledge of the origin of his inspiration, of his life, of his love life, before making any statement. It would have been a mistake to avoid this question.” Similarly fascinating will be À toi de faire, ma mignonne: Sophie Calle at the Musée Picasso-Paris, in which the French photographer and conceptual artist has been given carte blanche to make a work relating to the anniversary. “I’m curious to see how she will inhabit the museum,” says Widmaier Picasso.

Calle’s project confirms that this is not just a celebration but an opportunity to reappraise Picasso. “We’ve moved on from the shadow of Picasso over the art world,” says Widmaier Picasso. “It’s easier for other artists to play with him.” And he’s excited by this prospect. “It’s necessary for people who are not aficionados or specialists in Picasso to have a vision of his work and his life that is fresh, and not the dusty image of someone who died 50 years ago.”

Source: Sotheby’s, Museo Reina Sofía, The Met, Guggenheim, Wikipedia