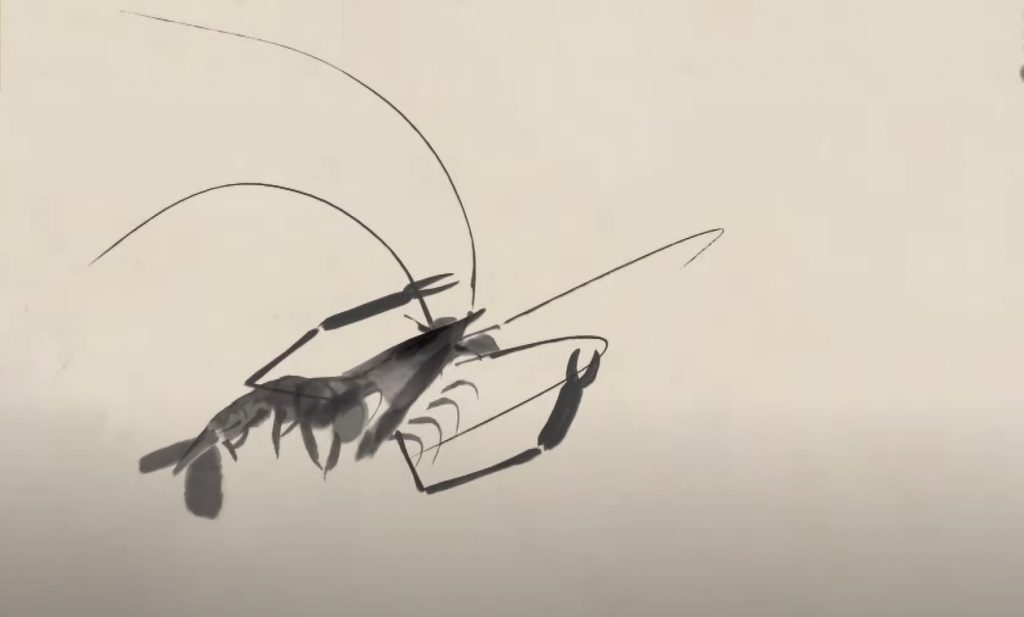

The side of the shrimp can immerse the viewer in a watery world. Even the slender whisker conceals a microcosm. The artist’s impression can truly transcend the reality.

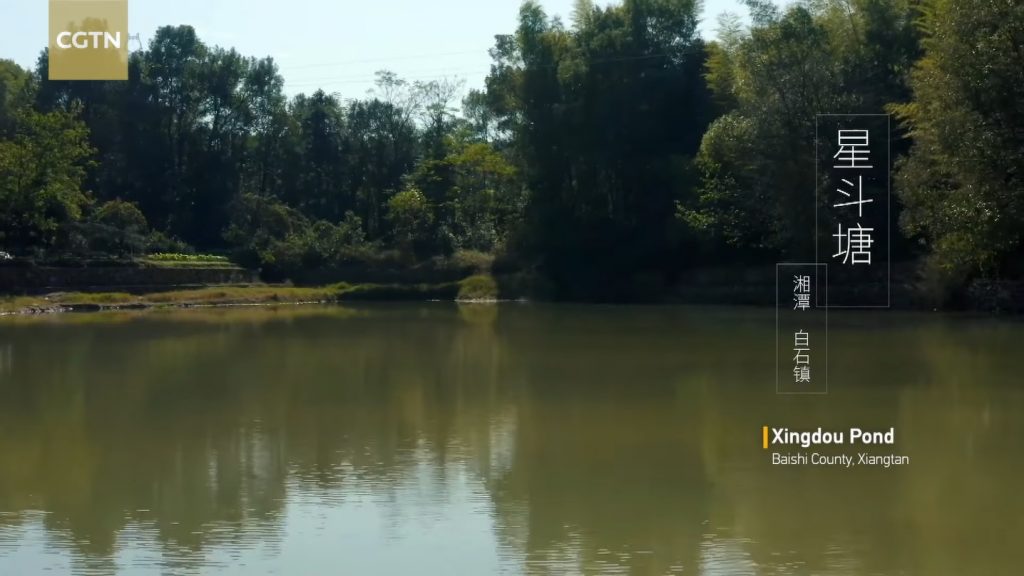

All these shrimps hail from Xiangtan Hunan, a world of grassy streams and ponds. They were all created by Qi Baishi, who later would win fame and prestige in Beijing.

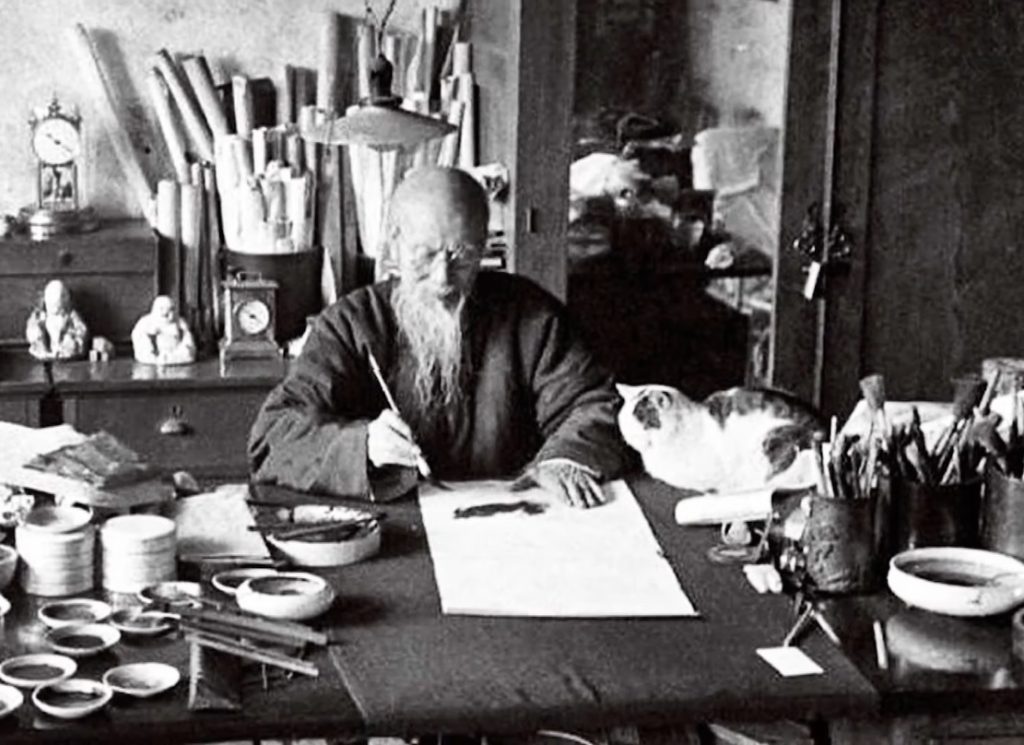

This courtyard at Kuache Hutong in Beijing used to draw numerous art connoisseurs. Even lay people knew about Qi Baishi the renowned painter who lived here.

He could render the shrimp so vividly that they seem to swim up the canvas.

Unlike his ancient predecessors, Qi Baishi used the different shades of ink for modeling the shrimp’s torso and head. The torso would look translucent while the head had a firm solidity. The deceptive casual strokes were actually deliberate and painstaking. Each section of the torso and each tremulous whisker conveys the resistance of water and the shrimp’s physical exertion.

These creatures are not passively subject matter. Rather they are asserting their presence.

“Qi Baishi’s skills in painting shrimps have been widely admired. As we can see, the swimming shrimp feels water’s resistance and buoyance. The resistance tends to act on these whiskers and result in these wavy curves. What set Qi Baishi apart from others, as observed by Mr. Li Keran, in his deliberateness. Even in painting a single whisker, Qi Baishi was very meticulous and slow. That is impressive. I want to note that the whisker’s rendition is enough to awe all later artists. You can’t help but admire his genius.” — Wu Hongliang, President of Beijing Fine Art Academy.

Con tôm sống động chỉ là một cư dân trong kho hình tượng của Tề Bạch Thạch.

The vivid shrimp is only one of the denizens in Qi Baishi’s visual repertoire.

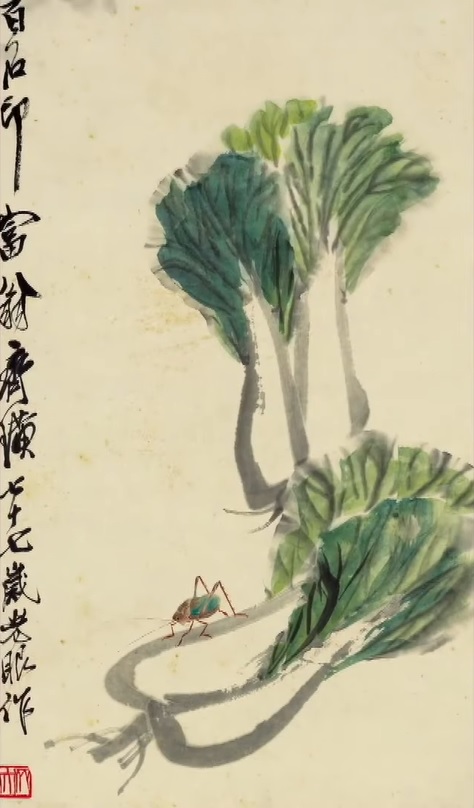

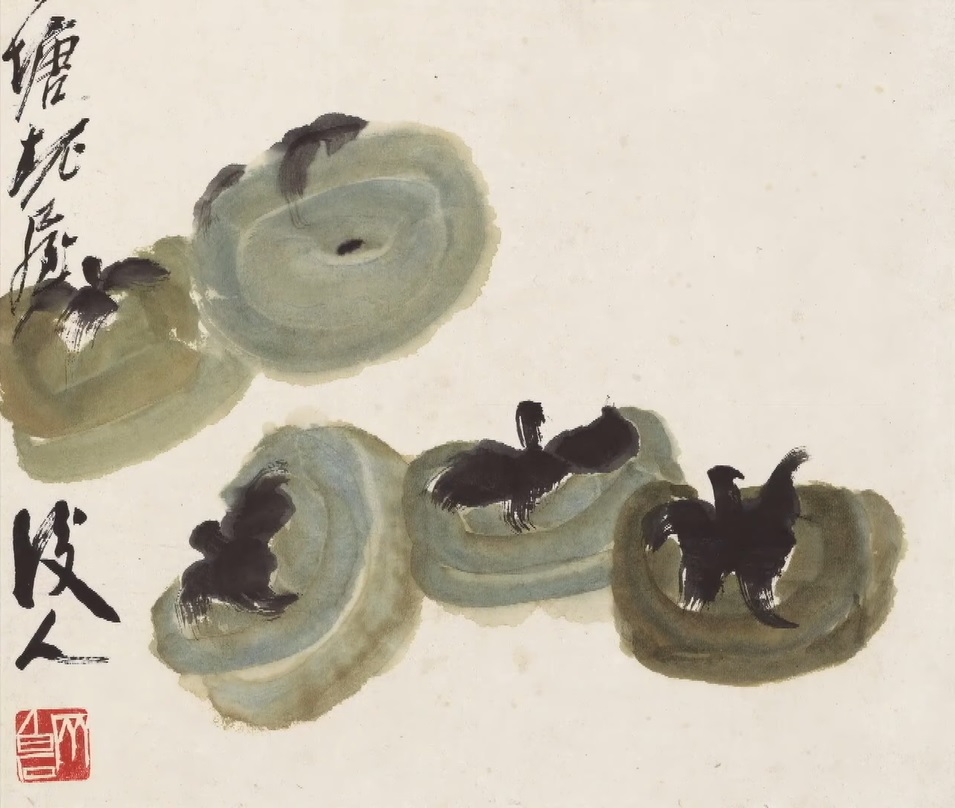

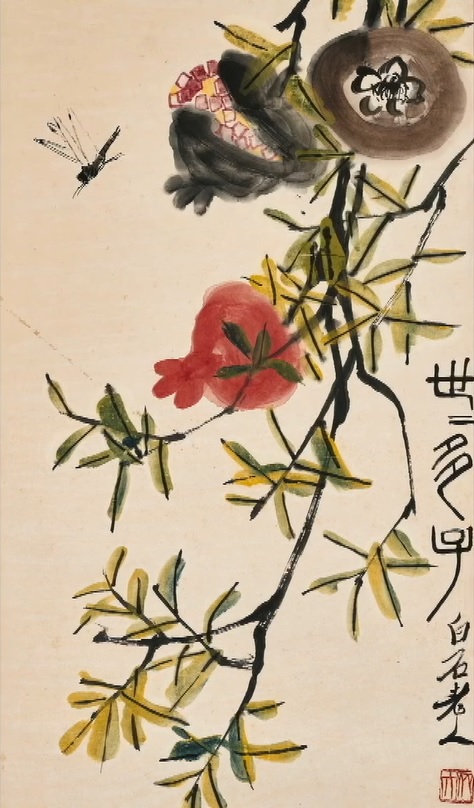

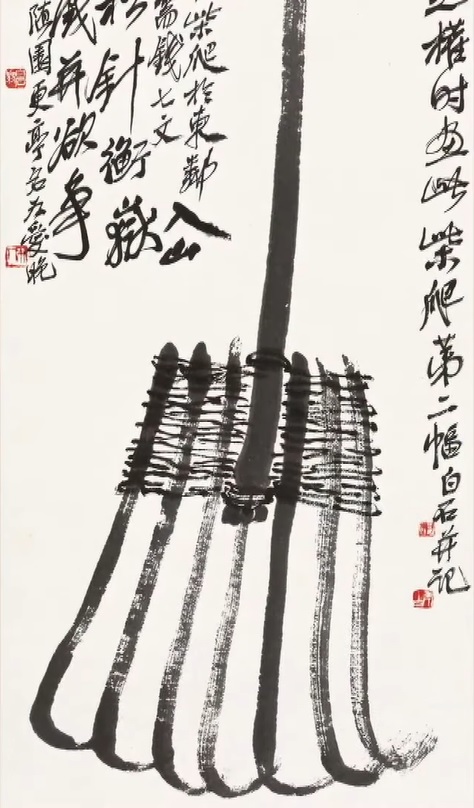

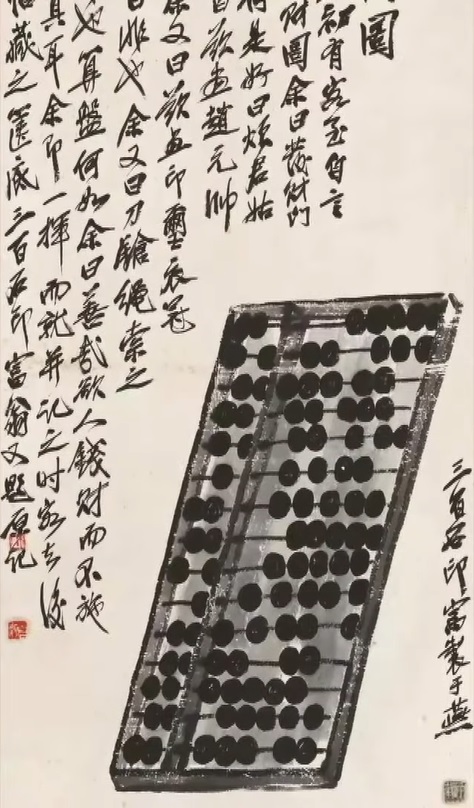

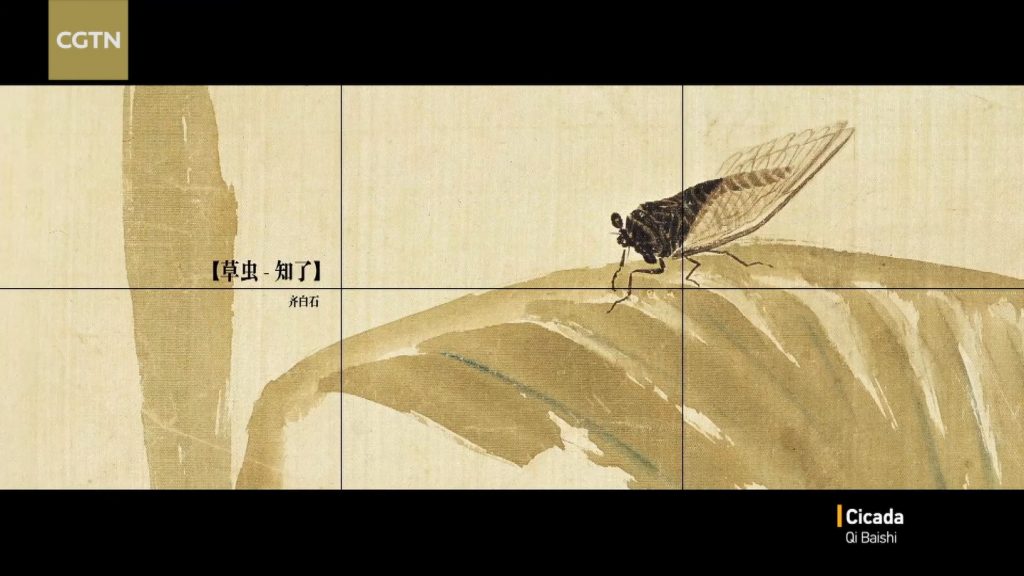

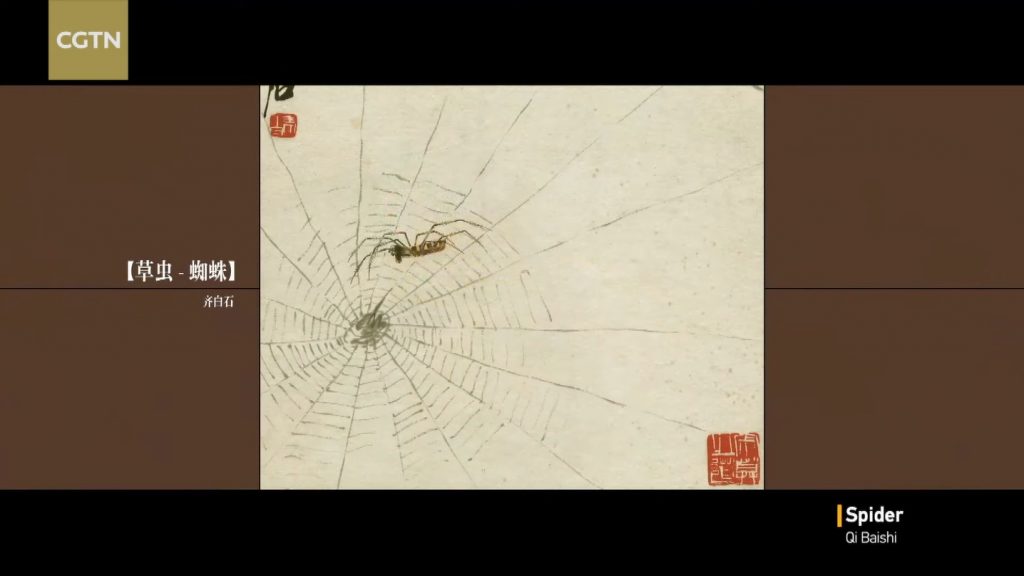

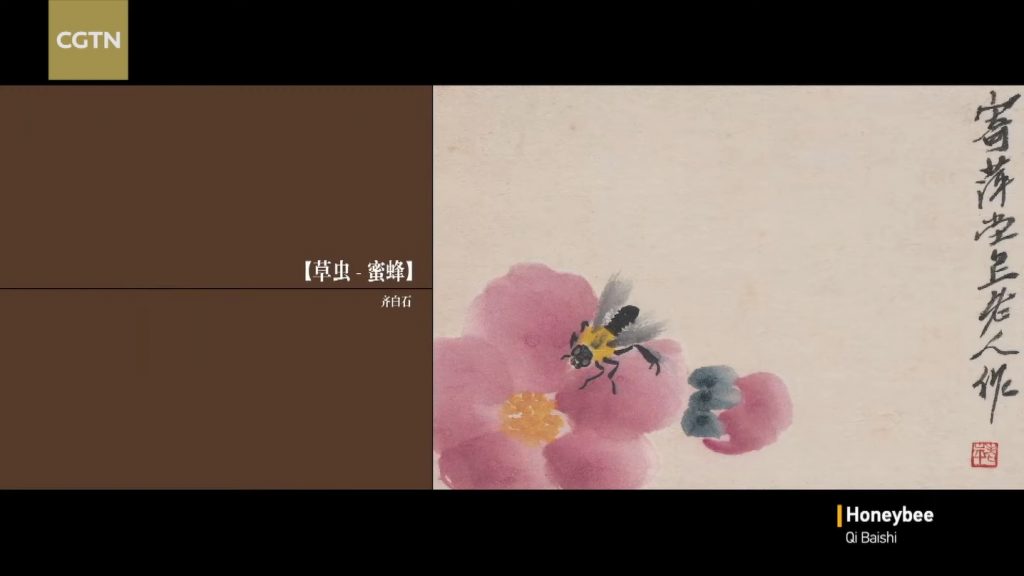

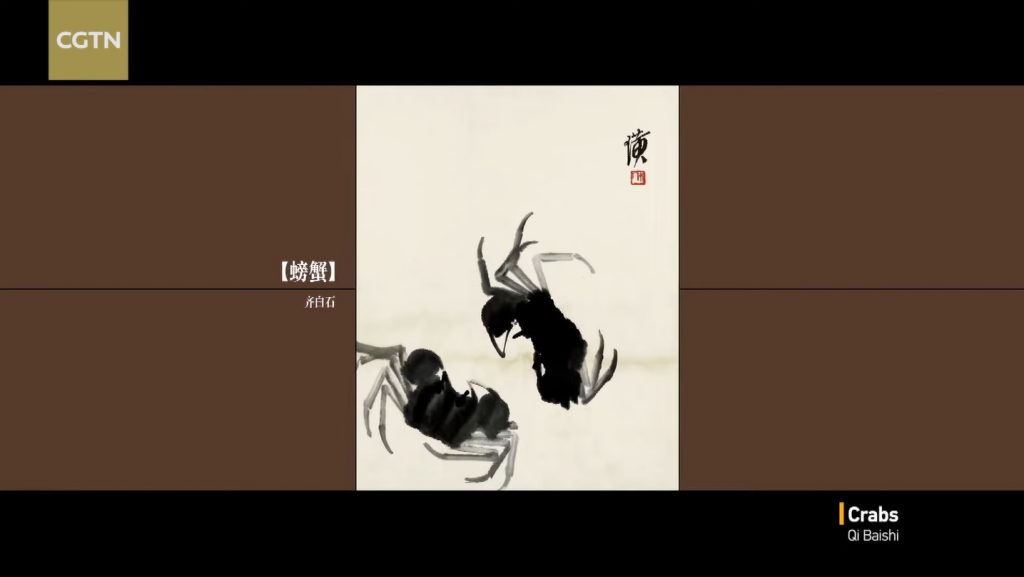

He also excelled in painting the cabbage which was rendered charmingly. And there are persimmons, pomegranates and other fruits, as well as various insects. He even painted daily household implements like the rake, basket and abacus.

People have wondered why he preferred to portray the mundane life. And how his brush strokes would instill such vividness.

To understand Qi Baishi’s imagery requires a glimpse into his life in rural Hunan.

Qi Baishi was born in a village. His was a peasant family. The countryside was a paradise, populated by chickens, ducks and all the birds and insects. In the ponds swamped the carefree shrimps. Their children grew and thrived like crops in the fields. When he was 19, he learned wood carving, then he studied drawing and painting, and came to be regarded as a literary figure.

The chirping insects in the countryside accompanied his younger years. There he lived several decades and seemed destined to spend the rest of his life and fade into the landscape. Then life took an abrupt turn. When he was 54, the chaos of war and banditry descended on his hometown. He found it necessary to flee north to Beijing and try to make a living by painting.

In Beijing, a city rendered of culture and history, there was a millennium old literati painting tradition. The subjects range from elegant floral still life, to sweeping landscape embodying human aspirations. But Qi Baishi — a new arrival from countryside was determined to be a type of zone.

The year spent in rural areas has instilled in him a love and worship of nature. So he painted the creatures living in the grass. This was a radical departure from the regular subjects of conventional fine art.

Qi Baishi’s imagery was the equivalent of the vernacular language in contrast to the heavily elusive art vocabulary back then. He embraced the mundane, rejected the cliched sentiment and refused to aid the ancient styles.

“What is interest? It is a human aspiration, which is based on a person’s taste and cultivation. In Chinese fine art, a lot depends on the quality of your taste.” — Wu Hongliang, President of Beijing Fine Art Academy.

After becoming an established master, in his residence at the Kuache Hutong, Qi Baishi still followed his regular routine. After a breakfast of plain noodles he will paint and study and write poetry until nightfall.

The paintings taken out of the courtyard were all inspired by the vivid rural memories and the most profound love for the motherland.

“Qi Baishi had a passion for life and a love for his hometown. He tried to make his works reach a wider audience. He was such an accomplished and erudite master painter.” — Feng Yuan, Honorary Chairman China Artists Association.

His love for rural life in an episode of national crisis inspired his principles fortitude.

As china was bullied and invaded, he wrote with indignation: “As I look out tearfully the land of China is no longer intact.”

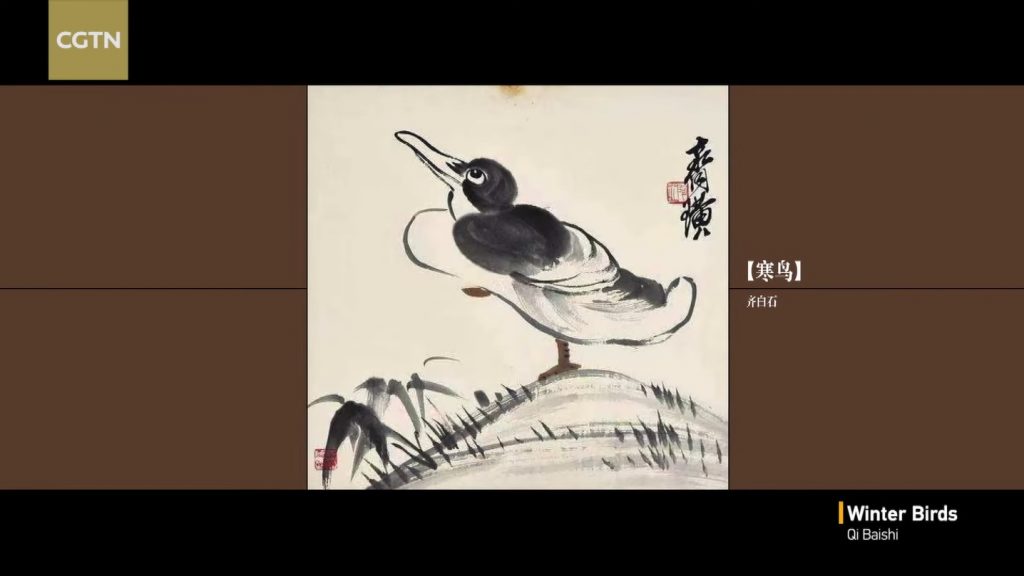

He indignantly painted the crab to allude to the arrogance of aggressors. He lovingly painted the winter birds can inspire the populace, and urge them not to bow their head to adversity.

Some advise him to tone it down, his answer was: “I was an old man in chaotic years, and death means little to me.”

This is a principled and genuine artist of the people. For his family and country, he had unending love.

In the 1970s and 1980s Qi Baishi’s shrimp imagery appeared on daily utensils like crockery and wash basins. Even the illiterate were familiar with Qi Baishi’s imagery. He was called the people’s painter.

“The popularity of his works is a testament to the people-oriented quality of his creative life. Everyone looking at his paintings can see the most loving, and most real soul of a great artist.” — Feng Yuan, Honorary Chairman China Artists Association.

To create for the people, to speak for the people and to express for the people. Qi Baishi brought fine art to the life of the common people and reached the multitudes. This was how his art merged into eternity.

Source: Youtube CGTN