We visited the artist’s studio to discuss unexpected connections, extractivism, and healing objects.

In an era of global capitalism, Latin American countries are subject to natural-resource exploitation; its historical foundations are linked to centuries of colonialism, which has had profound repercussions for the health of the continent’s peoples and the ecological equilibrium of its territories. Artist Adrián Balseca (b. 1989, Quito, Ecuador) works with this complex history, which is marked by mythologies that associate the extraction of resources with development, nationalism, and progress. In the process, Balseca reveals narratives hidden in the folds of the region’s politics and economy, dismantling antiquated symbologies. His work—comprising videos, installations, sculptural objects, and photographs—relies on a process of rigorous investigation and dynamic free-association, generating unexpected references that include elements of popular culture, art history, and social history. His artworks synthesize complex contemporary landscapes, navigating the contradiction of wanting to believe in the promises of modernity while imagining other ways of inhabiting the world.

As part of the Cisneros Institute’s continuing investigation of art and environment in contemporary Latin America, Maria del Carmen Carrión, the Institute’s project manager, visited the artist’s studio in Quito to discuss his work and the extractive history of Latin America.

Adrián Balseca in his studio, 2022

Your studio has an extraordinary view of Quito and the surrounding mountains. How long have you been working here?

This has been my studio since 2018, and my living space for about two years. The barrio is called Bellavista and indeed it has an incredible view of the city; it’s one of the oldest barrios in the northern part of Quito. It’s also one of the most outstanding pre-Incan human settlements on the hill of Guangüiltagua, which is the name of this area. The artist Oswaldo Guayasamín bought several plots of land here and that added value for the barrio. In fact, the site we’re on was one of Guayasamín’s former studios.

Adrián Balseca’s studio

On your work table there is a fascinating collection of books, visual materials, and objects. Looking at it makes me think that it functions as a display of your process. Can you speak about the unexpected connections between history, visual culture, and politics that are condensed in the pieces you produce?

Often, I immerse myself in research on topics that I’m interested in and which I feel require further exploration. I begin trying to understand it with 360° vision. How can I find out everything I can about this topic? I think that sometimes I like to organize ideas in a publishable manner. Since I’m a graphic designer, I put together these little digital brochures where I begin compiling images, references from history, art, and advertising; this helps me organize my ideas and begin to weave these places of encounter. Ideas start to emerge, the material starts talking to you, the archive starts talking to you. There’s always a strand there that has to do with graphics, popular culture, stories that have been mostly forgotten but are really dense and rich. In other words, they unleash different discourses: state discourses, economic discourses, design topics, which then condense themselves into an object. Therefore, the work consists in successfully finding the power that an object or a story might have, and from there continuing to unfold.

The work table

Can you talk about the connections you’re generating in your work Incisiones (2019)?

Incisiones is part of an investigation I began in 2016. Iquitos, in Perú, was one of the major rubber centers for the extraction and harvesting of this material in Latin America. From the end of the 19th century to the beginning of the 20th, the economic boom of this industry was founded on the enslavement of Indigenous Amazonian peoples as a labor force. The work consists of a series of photographs on 35mm slides, which are projected in a loop. The photographs document engravings I made by hand on trunks of Hevea brasiliensis wood, where the white “drawing” is the latex that flows from the tree. The designs were 80 tire-tread patterns, patented by the Goodyear, Pirelli, and Firestone corporations. From the beginning of the 19th century to the beginning of the 20th, tires were made of natural latex painted black, and in the mid-20th century they were transformed so that they could be produced with petroleum polymers.

Adrián Balseca. Incisiones. 2019

What materials were involved in your investigation?

I have guides such as the Tread Design Guide, which I’ve been collecting over time; that’s where I got the motifs with which I engraved the designs. I also used photographs published in the 1960s in Early Formative Period of Coastal Ecuador: The Valdivia and Machalilla Phases (Meggers, Betty J.; Evans, Clifford; Estrada, Emilio, 1965) by the Smithsonian, which show pieces from the Valdivia (4000–1600 BC) and Machalilla (1600–800 BC) cultures, which have a resemblance to the tire patterns. Also, there are several references to art history, like this 1982 catalogue of the Swiss artist Peter Stämpfli; I’m interested in his approach to the tire patterns from a Pop art perspective.

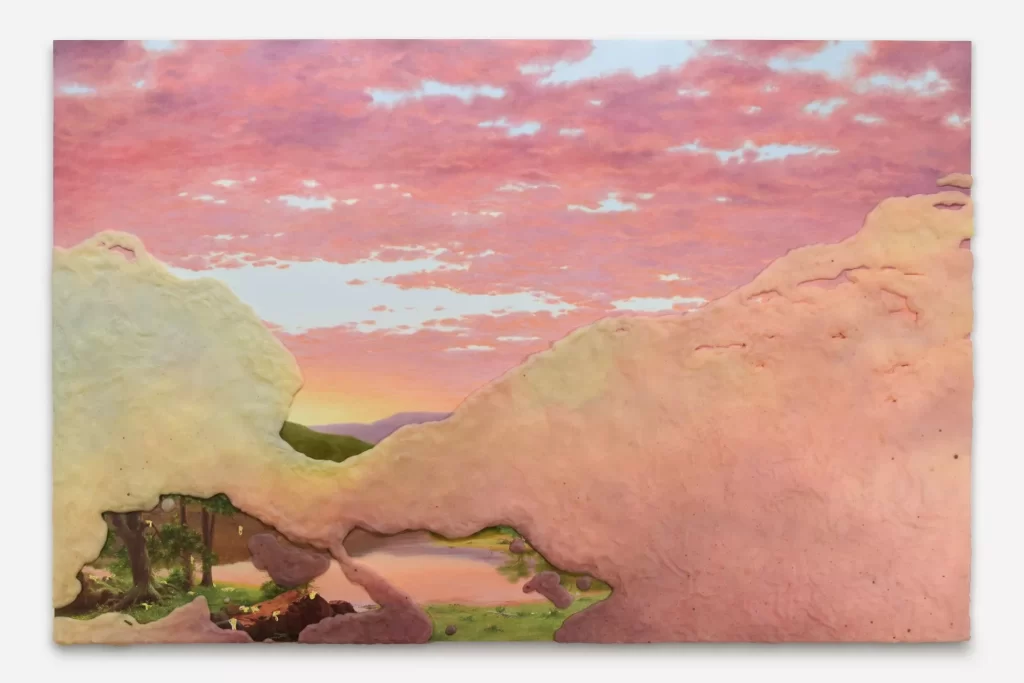

Adrián Balsdeca. PLANTASIA OIL Co. 2021

The various forms of resource extraction, and their promises and failures, are an important part of your body of work. In PLANTASIA OIL Co. (2021), which you produced in the middle of lockdown during the first year of the COVID-19 pandemic, you created a garden within the gallery space. It is a kind of survival garden, planted in containers used for petroleum products; the way in which the work is lit lends it a theatrical effect, because it generates a garden of shadows, a ghostly domesticated jungle on the gallery walls.

The selection of plants reflects the different extractive methods that preceded the oil boom in Lago Agrio, in Ecuador’s northeast. There are quinine plants, ishpingo, coca, among others, which are linked to a history of resource use before oil, like rubber and quinine. Then there are plants that are used today, like guayusa, which is consumed as a tea. Using 17 species, the idea was to put together this oasis in the middle of a gallery and plant each of them in barrels from businesses operating the petroleum fields in Ecuador since the late 1960s: Texaco, Chevron, Gulf, and Shell. These metal containers, which were used for storing petroleum derivatives like motor oil or pesticides, and which were never marketed in Ecuador, have been repurposed.

This pop-up of Amazonian plants emerged in the middle of the gallery, bringing the “jungle” back to the city. Ecolo (1992–95) by Enzo Mari, and images of oil barrels with plants in Pedro Almodóvar’s film Women on the Verge of a Nervous Breakdown (1988), are references that I wanted to make more complex, introducing native flora to the agent of their destruction: the oil industry. Instead of having just an aesthetic approach to recycling, the plants are occupying oil industry waste. It is a utopian perspective in which nature ends up taking back the territory occupied by oil companies.

How did the COVID-19 pandemic influence the way you work?

In a way the work is very much connected to the pandemic, because during the lockdown I was privileged to share a yard with my neighbors, who used to work for Texaco when it was operating in Ecuador. In that space, we spoke about the decline in price of oil, which is Ecuador’s primary export; because of the pandemic it fell to less than $36 per barrel. We also spoke about their experience with the company. Making this garden of common plants, which I find to be a very Latin American image, emerged from these conversations.

There is an additional component, a slide carousel, which is a collaboration with the Archivo Visual Amazónico: Elena Gálvez and Andrés Soto. They assembled this archive of representations of the jungle from throughout Ecuador’s history. Among the first images they included were photographs by Adolfo Maldonado, a Spanish doctor who lived in a community of the Shuar—an Indigenous people of the Amazonian regions of Ecuador and Peru—at the end of the 1980s, providing medical services. He was one of the first doctors in Ecuador who began to take a political position about his patients’ health. He organized a clinical archive and realized that cancer cases were closely related to the areas where his patients lived, as well as to the environmental impact of the oil industry. This happened in 1987 and 1988; in other words, there has been 20 years of oil extraction in Lago Agrio. Maldonado is a proto-ecologist here in Ecuador.

Obsidian on the work table

Tell me about these obsidian objects on the table.

They’re part of an ongoing project that only a few people know about. This is a crude piece of black obsidian from Mullumica (3,826 meters), a volcanic cliff that’s the largest archaeological source in Ecuador of artifacts made with this material. This volcanic glass is an igneous rock which was used by the first human settlements in the area, in part as a healing object.

This material, and the project that stems from it, are an important turning point in your work; you move from reflecting on what is happening in the world to observing what is happening in your own body.

Yes, it’s a work that’s cost me a great deal to develop, and it hasn’t been easy. Basically, the idea is to praise darkness. A wager to understand extractivism and the political by examining my own body. In 2011 I was diagnosed with Von Hippel-Lindau (VHL) Syndrome. I am interested in how capitalism has direct repercussions on health, and at the same time open myself to the healing that this volcanic glass brings as an element of purification, transformation, and regeneration in ancestral cultures.

In the historiography of extraction in Ecuador, obsidian is mentioned as the primary mineral material that human beings exploited; it was used in making spear points and axes, as well as other artifacts. In other words, this practice can be considered a kind of original extractivism.

This dark material is powerful; it was used in Abya Yala—the oldest known designation for an American territory—before the introduction of mirrors by the Spaniards during the Conquest. Have you ever seen a black mirror?

Source: MoMA