Karin G. Oen, curator

From January 18 to March 10, 2023, at the LGDR & Wei gallery in Hong Kong, the exhibition entitled ‘Scenes of This World: Modern Paintings from Singapore and Vietnam’ features more than 30 works by 11 artists from two countries. This article is written by curator Karin G.Oen, who is mainly responsible for the selection of paintings for the exhibition.

The School of Paris in the Southern Seas

Modern painting in Southeast Asia offers a series of complex narratives, filtered through the personal vantages of select transnational individuals. This exhibition, part of a larger reappraisal of 20th-century art from Southeast Asia, brings together works from artists associated with Vietnam and Singapore. In these locales, modern masters of painting maintained conceptual and stylistic links with painting styles, including Impressionism, Post-Impressionism, Fauvism, and Cubism, connected to the School of Paris—while the cities and nations in which they worked experienced massive change and upheaval. These affiliations were not only personal, but also conveyed through the curricula in the art academies where these painters trained, taught, and gathered. In addition to Europe and North America, their practices drew heavily from other parts of Asia, and sought to incorporate elements of a distinctly Southeast Asian vernacular into a new visual language to express neo-national, local, and hybrid identities. None of the artists presented here fit neatly into national or stylistic categories; however, they were all impacted by the natural and social environments around them, in some cases taking their memories of the landscapes of Southeast Asia with them as inspiration while they worked elsewhere in the world.

Nanyang Artists

In the 1940s in Singapore, then part of British Malaya, painters including Georgette Chen, Chen Wen Hsi, Cheong Soo Pieng, Liu Kang, and Chen Chong Swee became known as “Nanyang” artists—embracing the term frequently applied to ethnic Chinese organizations and artistic output in Malaya from the 1920s to the ’50s. These artists had trained elsewhere in the 1920s and ’30s—in Shanghai, Xiamen, New York, and Paris. In Republican China, art academies were founded in the early 20th century as part of the nation’s efforts to create infrastructure to train art teachers, who would, in turn, contribute to educating a well-rounded citizenry. The academies were established by artists who themselves had studied abroad in Japan and Europe, particularly in France. As political turmoil continued in China, artists and other intellectuals migrated to Malaya in the 1940s and ’50s, including Cheong Soo Pieng (1948), Chen Wen Hsi (1946), and Liu Kang (1946). Georgette Chen arrived in Penang in 1951 and moved to Singapore in 1953. Her journey included stops in Paris, New York, Shanghai, and Hong Kong. Lim Hak Tai, an artistic leader in Singapore who cofounded the Xiamen Academy of Fine Art in 1923, and, subsequently, founded the Nanyang Academy of Fine Art (NAFA) in 1938, advocated transposing the values explored in Chinese modern art in the 1920s and ’30s to the artists’ new environment in Nanyang, the Chinese term used for Southeast Asia (literally translating to the “Southern Seas”).

In 1952, a group of the Nanyang artists including Chen Wen Hsi, Cheong Soo Pieng, and Liu Kang, embarked on a collective trip to Indonesia, including time in Bali, that became a turning point in each of their careers. They were aware of the European Modernist legacy of Primitivism, as well as the European artists who had lived and worked in Bali in the 1930s and helped to inspire local modernist painting styles. The Nanyang artists approached this trip as exposure to Javanese and Balinese landscapes and culture, and, also, as a way to work through their identities as artists in the Symbolist sense: creatives invested in visual language and spiritual meaning. As 20th-century Chinese transmigrants in Southeast Asia, the journey presented a new and exciting opportunity, rather than a Modernist pathway to be followed.

École des Beaux-Arts d’Indochine

In Vietnam, part of French Indochina since 1887, the colonial relationship with France was one of many international and transhistorical factors present in 20th-century modern painting, along with Chinese, Cham, and Khmer influences. Anticolonial resistance and nationalist movements with communist inflections also colored the literary and artistic output of the 1920s, ’30s, and ’40s—a time of contentious politics, cultural confusion, and shattered ideals. The École des Beaux-Arts d’Indochine (EBAI) in Hanoi, cofounded by French painter Victor Tardieu in 1925, served as the primary convener of artistic talent. EBAI’s early graduates included Le Pho, Mai Trung Thu, Nguyen Gia Tri, Nguyen Phan Chanh, and Vu Cao Dam, many of whom spent significant portions of their careers in France. [Such as Lê Phổ, Mai Trung Thứ and Vũ Cao Đàm]

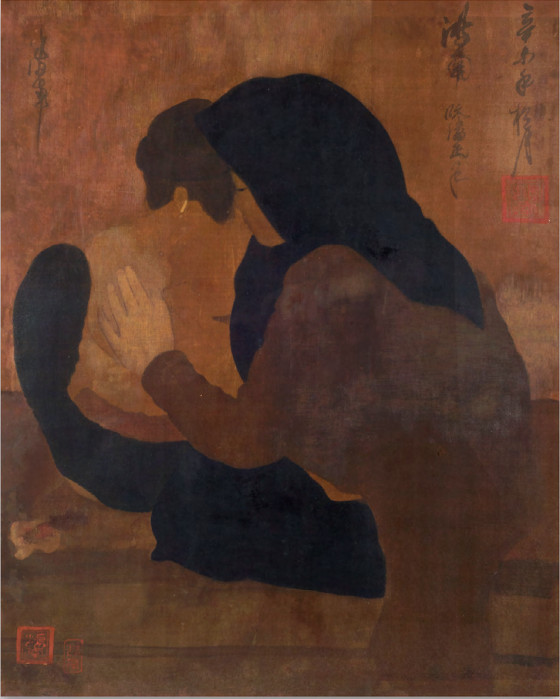

Under the supervision of Tardieu and other French faculty members including Joseph Inguimberty, EBAI taught the Beaux-Arts curriculum along with painting techniques that incorporated local Vietnamese art materials including silk and lacquer—part of efforts to forge a distinctly Vietnamese modern art. Nguyen Phan Chanh’s early education was conducted exclusively in Chinese in preparation for the Confucian civil service exams that were abolished in the late 1910s before he could take them. He therefore came to EBAI with skills in traditional calligraphy that eventually translated into his preference for painting in ink and color on silk (instead of oil on canvas), a hybrid of Eastern and Western painting promoted by Tardieu. Le Pho, on the other hand, embraced oil painting, although he also practiced painting on silk as well as lacquer painting, another area in which EBAI explored artistic fusion. He eventually studied at the École des Beaux-Arts de Paris in the early 1930s, and, subsequently, settled in Paris in 1937 after first returning to Vietnam and teaching at EBAI for several years. During this time, he also traveled to China and Cambodia to study the region’s art history, making painting on silk a significant aspect of his practice. Mai Trung Thu also settled in Paris in the late 1930s [1937 to be exact], after teaching art in Hue for several years and developing his métier of idyllic landscapes, peasants, and mothers and children, often in gouache on silk. These seemingly pastoral themes of Vietnamese life, pursued even after Mai relocated to France, bely the critical nostalgia employed by many painters— especially those from elite Mandarin families like Mai’s—during this turbulent time for Vietnam. Painter and sculptor Vu Cao Dam grew up in a multilingual Catholic family where French culture was respected and studied. His early training at EBAI was immediately followed by a scholarship to train in France starting in 1931, after which he never returned to live in Vietnam.

Nguyen Gia Tri studied oil as well as lacquer painting—a hybrid medium that explored lacquer as a painterly material in the Western tradition despite its traditional use as a lustrous protective finish for sculpture and furniture. This was the medium for which he became best known, although he also worked as an illustrator for progressive literary magazines that expressed anticolonial sentiments and self-reliance as the basis for Vietnamese nationalism. Such endeavors that combined poetry, prose, and art were part of a politically tinged youth culture that gave voice to the anxiousness of a generation through satire and gloom. The Vietnamese painters of this era, engaged with the color palettes and approaches of the School of Paris, often embraced idyllic genre painting including landscapes with lush floral imagery and scenes of domestic life. These tranquil subjects, however, coexisted with the malaise, tension, and tumult of the generation that came of age in the 1930s [Because Vietnam at that time was still under French domination]. The title of this exhibition further refers to the creative expression of this modern duality. It is taken from a 1937 poem by then 17-year-old Che Lan Vien, one of the many young writers who looked to art as an escape from the difficult times in which they lived, and, who craved the solace of illusion “to put out of mind for a few minutes the scenes of this world.”

Liu Kang, Silent Beauties, 1998, Oil on canvas, 42⅛ × 42⅛ inches (107 × 107 cm)

Georgette Chen, Mooncakes and Lanterns, c. 1960s, Oil on canvas, 25⅝ × 20⅞ inches (65 × 53 cm)

Cheong Soo Pieng, Two Balinese Girls, 1957, Oil on Masonite board, 31⅞ × 24 inches (81 × 61 cm)

Chen Wen His, Balinese Ladies, c. 1950s, Oil on canvas, 471/4× 471/4 inches (120 × 120 cm)

Le Pho, Les joueuses de cartes (Card players), c. 1940, Ink, water-colour and gouache on silk, 165/8 × 111/4 inches (42.3 × 28.5 cm)

Nguyen Gia Tri, Trois femmes, 1934, Oil on canvas, 461/8 × 351/4 inches (117 × 89.5 cm)

Nguyen Trung, Flower, Fruit and Dream, 1999, Oil on canvas, 59¹/16 × 707/8 inches (150 × 180 cm)

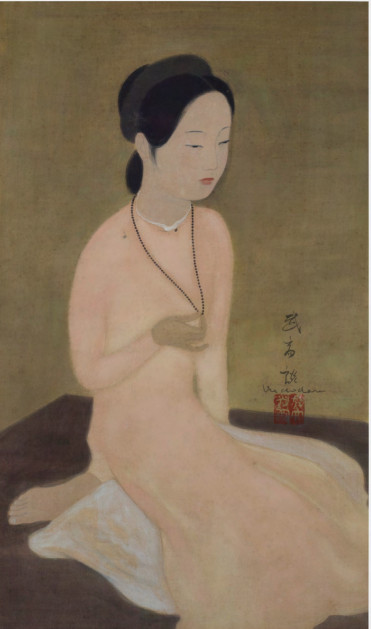

Vu Cao Dam, Jeune femme agenouillee tenant son collier, c. 1940s, Ink and gouache on silk, 273/4 × 161/4 inches (70.5 × 41.2 cm)

Mai Trung Thu, Le Thé à Hué, 1937, Oil on canvas, 271/2 × 39 inches (70 × 99 cm)

Alix Ayme, Portrait of a girl, c. 1935, Oil on canvas, 22 × 18, 1/8 inches (56 × 46 cm)

Nguyen Phan Chanh, L’acupunctrice, 1931, Ink and gouache on silk, 243/8 × 195/8 inches (62 × 50 cm)

Source: LGDR