While many stories of surrealism have focused on Paris in the 1920s, the revolutionary movement inspired and united artists around the world. Over the past century surrealism has been expressed in distinct ways in response to local concerns, always reflecting its core aims to subvert reality, challenge authority and imagine new worlds

Abdul Kader El Janabi, ‘Visa sans planète (Visa without a Planet)’ 1983–90

Everyone knows what ‘surreal’ means – it’s become an everyday adjective signifying the not quite believable, the odd, weird, unnatural, supernatural, inexplicable. But this popular usage cannot pass as defining one of the most complex and far-reaching movements of the last hundred years. While it is often treated as an historical moment in European art history, surrealism was not drawn up by its founders as an abstract, fixed system. The title of the exhibition coming to Tate in February, Surrealism Beyond Borders, highlights its transnationalism but raises an interesting question: is it to be considered as a worldwide brand, recognised for its characteristic features, or is it to be sought in individual specific manifestations, anywhere in the globe, with local meanings? So what is surrealism?

Wilhelm Freddie, ‘Min kone ser pa benzinmotoren hunden ser paa mig (My Wife Looks at the Petrol Engine, the Dog Looks at Me)’ 1940

‘What is Surrealism?’ was the title of the lecture given by the French poet and co-founder of surrealism André Breton in Brussels in 1934, and subsequently published as a pamphlet, in which he explained surrealism in its then current situation through passages from his writings up to that point. At this time the surrealists were directly engaged in anti-fascist activities – notably in alliance with the group Contre-Attaque founded by the philosopher Georges Bataille – alongside their existing commitment to anti-colonialism, and Breton’s lecture is still hard to beat as an account of the origins, early history, development and purposes of the movement. But more than that, it points to the reasons why its orientation, attitudes and ideas could speak and still speak to so many different people in different circumstances all over the world. It includes the famous definitions of surrealism from his first Surrealist Manifesto from 1924, which formulated the thoughts of the group at that point:

SURREALISM, n. Pure psychic automatism, by which it is intended to express, verbally, in writing, or in any other way, the real functioning of thought. The dictation of thought in the absence of any control exerted by reason and outside all aesthetic or moral preoccupations.

ENCYCL. Philos. Surrealism rests in the belief in the superior reality of certain forms of association neglected heretofore; in the omnipotence of the dream and the disinterested play of thought. It tends to ruin, definitively, all other psychic mechanisms and to substitute itself for them in the solution of the principal problems of life.

A definition is not an explanation. These manifesto definitions were, Breton explains, subordinate to the fundamental turn of thought distinctive to the time: a reaction against the rule of logic and the prevailing mood of absolute rationalism, which under the guise of progress had banished everything that could be called superstition or fancy. So the marvellous, magic (not mystification) and the imagination were to be revalued. ‘Pure psychic automatism’, inspired by Sigmund Freud’s discoveries of the unconscious and the importance of dreams, while periodically reaffirmed in verbal and visual experiments, in no way encompasses surrealism’s reach, which was to prove unpredictable.

Although the visual arts were peripheral in the first formulations of surrealism, they were to prove its most famous and influential manifestation. Exhibitions of surrealism have a long history of controversy, whether they are surrealist exhibitions – that is, organised by surrealists in the name of surrealism – or exhibitions about surrealism organised by art historians and curators. (I used to think the distinction was clear cut, but now have doubts.) The first of the latter was Fantastic Art, Dada, Surrealism in 1936–7, at the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) in New York, organised by its first director, Alfred H.Barr Jr; struck by the rip-roaring success of the International Surrealist Exhibition at the Burlington Galleries in London earlier that year, Barr fancied taking it to New York. He had not bargained with the active intervention of Breton, the poet Benjamin Péret, and other comrades, who regarded any such exhibition as, basically, theirs. Barr, who had his own ideas of how to present surrealism, tried to bypass Breton by negotiating directly with the artists involved, fairly certain they would welcome exposure in the most important US museum. The ensuing fracas resulted in a relatively successful compromise.

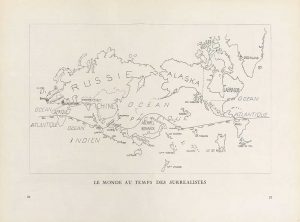

In June 1929, a curious hand-drawn map titled ‘The World in the Time of the Surrealists’ appeared in the pages of the surrealist Belgian magazine Variétés. Two years later, it reappeared in the Mexican periodical Contemporáneos. In the map, territories shrink and swell around an equator that buckles across the earth’s oceans, with the Pacific taking the accepted place of the Atlantic in the centre.

The drawing relayed the broad range of networks and interrelated global exchanges of surrealism at the time of its making, and hinted at a growing anti-imperialism. As a surrealist challenge to a long-fixed view of the world and its imbalances of power, the map questions the systems of information and values that have typically excluded, rather than included, voices beyond the West.

Image © Metropolitan Museum of Art, photo by Mark Morosse

During the preparation of the exhibition Dada and Surrealism Reviewed, which opened at the Hayward Gallery in 1978, one of the main points of discussion was when the exhibition should end: With the end of the Second World War? With the death of Breton in 1966? William Rubin’s 1968 Dada, Surrealism and their Heritage, an exhibition that was unquestionably not a surrealist exhibition and was greeted with demonstrations by surrealists outside MoMA, had ended with the International Surrealist Exhibition in Paris of 1947. Rubin wanted to emphasise formal continuities between the automatism of the semi-abstract paintings of artists like Arshile Gorky and the abstract expressionists. Dada and Surrealism Reviewed, on the other hand, was structured around the dada and surrealist reviews, so effectively ended with the last of the Paris surrealist reviews published in Breton’s lifetime, La Brèche (1961–5). But the relationship with surrealism as a movement was, again, complicated. There were former, and possibly active, surrealists among the organisers, not to speak of the involvement of many living artists, such as Eileen Agar. However, connections with contemporary surrealist groups were virtually non-existent. A flurry of exhibitions and publications in 1978, such as the Chicago surrealist Franklin Rosemont’s important anthology What is Surrealism?, proved it was a living movement.

Hector Hyppolite, ‘Ogou Feray also known as Ogoun Ferraille’ c.1945

Surrealism Beyond Borders, now at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York and opening at Tate Modern in February, is a startling exhibition of surrealism, in temporal, geographical and other senses. It recognises, as the curators say, ‘the continuing life of surrealism today’, even if perforce the focus is on the first 50 years of the movement following its founding in 1924. Their starting point is the map ‘The World in the Time of the Surrealists’, published in the Belgian magazine Variétés in 1929, which redrew the territories of the globe to express the surrealists’ disgust with European imperialism, to celebrate alternative orders and to highlight non-Western cultures. So the colonising imperialist powers of Britain and France are annihilated, Soviet Russia is prominent, and Oceania made central together with Easter Island and the indigenous lands of the Northern Pacific Coast of America (‘Alaska’). The surrealists’ love of the sculptures and power objects from cultures free of the homogenising influence of artistic modernism, demonstrated in the map, is now a sensitive issue, marred by the term ‘primitivism’.

The wide-reaching impact of surrealism is shown in the diversity of reactions and adaptations it has undergone in work by collectives, by groups and by individual artists from all over the world, including, as well as Europe, China, Japan, Korea, Martinique, Haiti, Cuba, Egypt, Syria, Mexico, Peru, Sri Lanka and New Zealand. While the movement was committedly antinationalist, at the same time it was precisely the specific and very various conditions in different places producing local responses which underline the anti-colonial and resistant character of surrealism, and the relevance of the complex issues this raises today.

Ted Joans’s Long Distance 1976–2005 with 134 contributions from artists around the world

© Ted Joans estate, courtesy of Laura Corsiglia. Photo by Joseph Wilhelm / Meridian Fine Art

The poet Clément Magloire-Saint-Aude, who participated in the Les Griots movement of black consciousness in Haiti in the 1930s, wrote in the Port-au-Prince newspaper Le nouvelliste in 1942: ‘We are neither dreamers nor idealists nor unrealistic … Surrealism is an attitude of reaction, defiance and distrust.’ In 1945, on the occasion of Wifredo Lam’s exhibition at the Centre d’art in Port-au-Prince, Breton came to lecture in Haiti, where he also met the voodoo practitioner and painter Hector Hyppolite. The lectures, which were hardly incendiary, had a dramatic effect, being partially responsible for the collapse of the government. As Michael Richardson explained in the anthology Refusal of the Shadow: Surrealism and the Caribbean, cultural values in Haiti have a political impact that they lack in the West; Breton’s talks articulated a popular, latent surrealist quality in the voodoo religion, in the art and the ways of being that were marginalised by the ruling elite.

A different search for identity in Martinique, which, unlike Haiti, where independence from France was declared in 1804, is a département of France, found in surrealism confirmation and support of their resistance to the policy of cultural assimilation. In the magazine Tropiques, published between 1941 and 1945 in Martinique’s capital, Fort-de-France, Suzanne Césaire described surrealism as ‘the tightrope of our hope’. Breton chanced on a copy of Tropiques in 1941 in Fortde- France when he was on his way as a refugee from occupied France to the United States: ‘I could not believe my eyes. What was said there was what it was necessary to say.’ The journal is intellectually invigorating, combative and poetic. Suzanne’s husband, the poet Aimé Césaire, had published Cahier d’un retour au pays natal a couple of years earlier; described by Breton as ‘the greatest lyrical monument of our time’, this poem contributed to the start of Négritude, an international anti-colonial movement that sought to reclaim the value of Black history and culture. Suzanne Césaire wrote in the fifth issue of Tropiques in April 1942:

Here we are called upon to know ourselves … Surrealism has given some of our possibilities. It is up to us to find the others. With its guiding light.

And let me be clear:

It is not all about a backwards return, a resurrection of an African past that we have learned to know and respect. On the contrary, it is about the mobilisation of every living strength brought together upon this earth where race is the result of the most unremitting intermixing.

Tropiques hums with the energy of the lines of enquiry into black identity in Martinique and more broadly in the Caribbean: Suzanne Césaire on the German ethnologist Leo Frobenius’s controversial studies of African civilisation; creole and Black-Cuban tales such as ‘Bregantino Bregantin’ collected by Lydia Cabrera; articles celebrating the tropical flora and fauna of the islands; the surrealist Pierre Mabille, working as a doctor in Haiti, on the ‘Realm of the Marvellous’; Victor Brauner on his own paintings; Wifredo Lam; and always the poets, including Césaire, Breton, Charles Duits and others.

Mayo ‘Coups de bâtons (Baton Blows)’ 1937

Alongside the strong impulse surrealism brought to diverse localities, there are numerous crosscurrents and interconnections that were wide and free in their expressions. The gigantic collective work, Long Distance, was a Cadavre exquis (the drawing game ‘Head/Body/Legs’) started by the surrealist poet, artist and musician Ted Joans in 1976 and continued, in collaboration with over 130 contributors – starting with the British surrealist Conroy Maddox and encompassing artists and writers such as the Mozambican painter and poet Malangatana Ngwenya and Abdul Kader El Janabi, founder of the first surrealist Arabic review – until 2005.Surrealism is also full of surprises and lost histories, like that of the surrealist groups in China in the 1930s, submerged by the Sino-Japanese war of 1937 and then suppressed under the People’s Republic of China. The engagement with surrealist ideas was sometimes actively critical as in Japan, where a ‘scientific surrealism’ was advanced to counter what was regarded as the emotional and individualistic nature of Paris surrealism, featuring a mechanical world but with the jarring juxta-positions characteristic of surrealist collage. Sometimes the well-known prejudices of surrealism – against Western religions, for example – run up against intriguing variants, as in the Philippines, where Catholicism underwent a re-imagining. Music, famously condemned by Breton, was nonetheless an important field for experimentation for some groups, and in jazz, surrealism found remarkable analogies. Ted Joans said:

Jazz is my religion and surrealism my point of view. Jazz is the most democratic art form on the face of earth, it’s a surreal music, a surreality. Surrealism like jazz is not a style, it’s not a dogmatic approach to the arts like cubism…Surrealism was not conceived as an art movement, and although now most familiar through its visual manifestations, is not, as Joans says, a style, confined to a single form of expression. The range of works made in or linked to its name worldwide, rather than asserting definitions, surely keeps open the question, ‘What is Surrealism?’

Source: Tate