The exhibition ‘Van Gogh in America’ charts which pieces were snapped up by U.S. museums and which ones got away.

Vincent van Gogh, Self Portrait (1887). Collection of Detroit Institute of Arts, City of Detroit Purchase, 1922.

Today, Vincent Van Gogh is one of just a handful of artists’ names that seemingly everybody knows. But a century ago, not a single U.S. museum owned one of his works until the Detroit Institute of Arts (DIA) made the then-radical purchase of a diminutive 1887 self-portrait by the Dutch painter.

Now, the museum is looking back at the arrival of Van Gogh’s art in the U.S. with an exhibition of 74 original works by the artist. The show features pieces that now belong in museum collections across the country as well as those that slipped through America’s fingers, ultimately landing at institutions overseas.

Today, there are 125 Van Gogh paintings in U.S. museums, including beloved masterpieces like Starry Night (1889). (A mainstay of the collection of New York’s Museum of Modern Art, it rarely travels, so the DIA instead settled for 1888’s Starry Night Over the Rhone River from the Musée d’Orsay in Paris.)

“Van Gogh in America” is the first show of its kind, and it sets out to explain why a country that recently hosted nearly 50 “immersive” Van Gogh experiences at once had such a hard time embracing the artist’s bold color choices and expressive brushwork when first presented with the opportunity to buy the original canvases.

Vincent Van Gogh, Starry Night Over the Rhone River (1888). Collection of the Musée d’Orsay, Paris. © Musée d’Orsay, Dist. RMN-Grand Palais/Patrice Schmidt.

“The scholarship on Van Gogh is incredibly vast, so it was hard for me to comprehend that there had not been an overall study of his reception in the U.S.,” the museum’s curator of European art, Jill Shaw, told Artnet News.

The idea for the show dates back to January 2016, when Shaw had been on the job for just three days. DIA director Salvador Salort-Pons suggested organizing some kind of Van Gogh exhibition, and Shaw immediately started thinking about possible angles—particularly ones that would highlight the museum’s own holdings of the artist’s work.

The first step was to confirm that the DIA’s claim to be the nation’s first museum to own a work by Van Gogh held up. (It’s true!)

“I knew that we bought it in 1922, which to me seemed pretty late,” Shaw said. (A handful of private collectors were quicker to embrace the artist, with Albert C. Barnes, John Quinn, and Katherine S. Dreier making the first personal purchases in 1912.)

Vincent Van Gogh, Portrait of Postman Roulin (1888). Collection of the Detroit Institute of Arts.

Shaw’s research soon revealed that, compared with some European countries, such as Germany, the U.S. was definitely behind the curve when it came to Van Gogh, who died in 1890. In fact, it was that European interest that drove up his market and made buying his pictures a less affordable option for U.S. institutions that might want to take a chance on an artist not yet embraced by conservative prevailing tastes.

“Prices were high, and Americans weren’t ready to pay those prices for an artist they couldn’t quite wrap their heads around,” Shaw said.

The exhibition includes loans from over 60 individuals and institutions—arrangements that had to be renegotiated when the show was postponed from 2020 due to the pandemic and some of the art was no longer available. But the delay also gave Shaw time to revisit the checklist in light of her most recent research and include works whose relevance to the presentation’s thesis hadn’t come to light until too late in the game to secure them for the initial dates.

Vincent Van Gogh, Van Gogh’s Chair (1888). Collection of the National Gallery, London.

“It was this amazing moment that I don’t think I’ll ever get again—and I don’t think I want to!” Shaw said.

The exhibition opens with one of the paintings that got away, Van Gogh’s Chair (1888), which was for sale at several U.S. shows in the early 1920s, but ultimately landed at the National Gallery in London. The artist is conspicuously absent in the work, which depicts his pipe and tobacco pouch resting on a simple chair.

Although Van Gogh never visited the U.S., his work debuted in the States in 1913, at the famous Armory Show. Opening in New York before traveling to Chicago and Boston, the exhibition marked the arrival of Modern art onto American shores. The Dutch artist, however, was overshadowed by such infamous works as Marcel Duchamp’s Nude Descending a Staircase, and all 21 Van Goghs on view went unsold. (Two were loans from Quinn and Dreier and not for sale.)

The DIA exhibition includes a wall covered with a full-scale photograph of Van Gogh’s Armory Show presentation, to help transport viewers back across the decades, to a time when his work would have been strange and unfamiliar.

If Americans back then knew Van Gogh at all, it was from black-and-white reproductions in newspapers, which gave no indication of the vibrant colors that defined his canvases. The Armory Show also wasn’t the best introduction to Van Gogh’s oeuvre.

“It had works from all periods of his career, but it wasn’t a very coherent selection, which probably played a role in people not understanding who Van Gogh was as an artist,” Shaw explained. “And there were some people touting that old conservative line, that he was just wasting art materials. They were just not ready to accept his color, his brushstrokes, his non-naturalistic style of painting.”

Indeed, one critic at the time complained that Van Gogh “spoiled a lot of canvas with crude, quite unimportant pictures.”

It was Van Gogh’s sister-in-law, Johanna van Gogh-Bonger, who was largely responsible for changing that narrative and charting the artist’s posthumous rise to fame. Dedicating her life to promoting his work, Van Gogh-Bonger lent 85 pieces to U.S. exhibitions between 1913 and 1920.

Only three of those works found a buyer—a single collector, named Theodore Pitcairn—and all at New York’s Montross Gallery, which staged Van Gogh’s first retrospective in the country in 1920.

At least one critic recognized that U.S. institutions had been missing out on an important piece of art history.

“During the thirty years’ nap in which our museum directors and collectors have been indulging, amateurs on the other side of the water have not been asleep,” Henry McBride wrote during the Montross exhibition. “To have bolted the doors so long against Van Gogh, to have kept aloof from him during all the years in which he was, so to speak, upon trial, does not appear to throw a pretty light upon our museums.”

In 1921, New York’s Metropolitan Museum of Art held its first exhibition of Impressionist and Post-Impressionist art, featuring four Van Gogh paintings. But when it came to acquisitions, the DIA struck first, making its move on January 31, 1922, at an auction at New York’s Plaza Hotel.

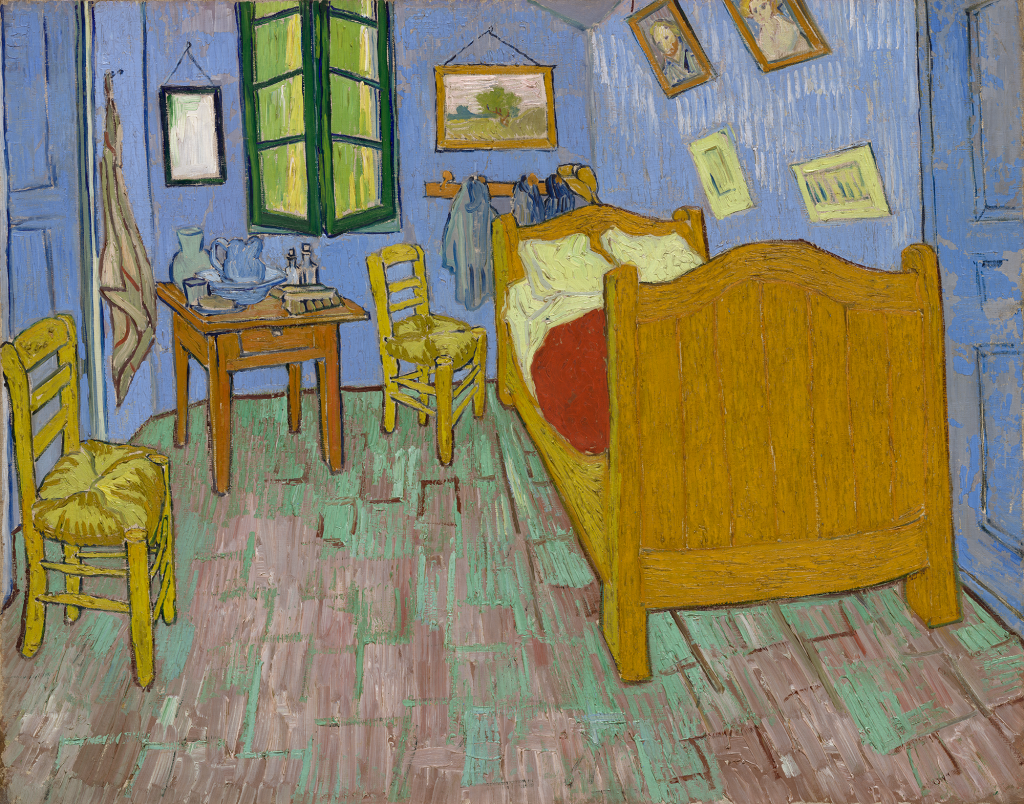

Vincent Van Gogh, The Bedroom (1889). Collection of the Art Institute of Chicago.

With a winning bid of $4,200—which would be about $75,000 today—the City of Detroit Arts Commission president Ralph. H. Booth secured the Van Gogh self-portrait for the institution. It was still an expensive purchase, but the price represented a considerable discount from those set by Van Gogh-Bonger, bringing the work within the DIA’s budget. (Luckily, Pitcairn, who is said to have also been interested in the painting, didn’t show up to the auction, so the museum was able to avoid a bidding war.)

Looking back, it seems surprising that U.S. museums took so long to catch on to Van Gogh’s genius. But in 1922, the DIA purchase was a “courageous” decision—future DIA director Wilhelm Valentiner wrote to Booth following the acquisition, saying that “I hope it will be appreciated by the people in Detroit if not now, I do not doubt, some time in the future.”

Although other U.S. museums slowly began picking up Van Goghs of their own, it took some time. The Art Institute of Chicago accepted a donation of three Van Gogh canvases (plus one later proved to be a forgery) from Frederic Clay Bartlett in 1926, including the famous The Bedroom (1889).

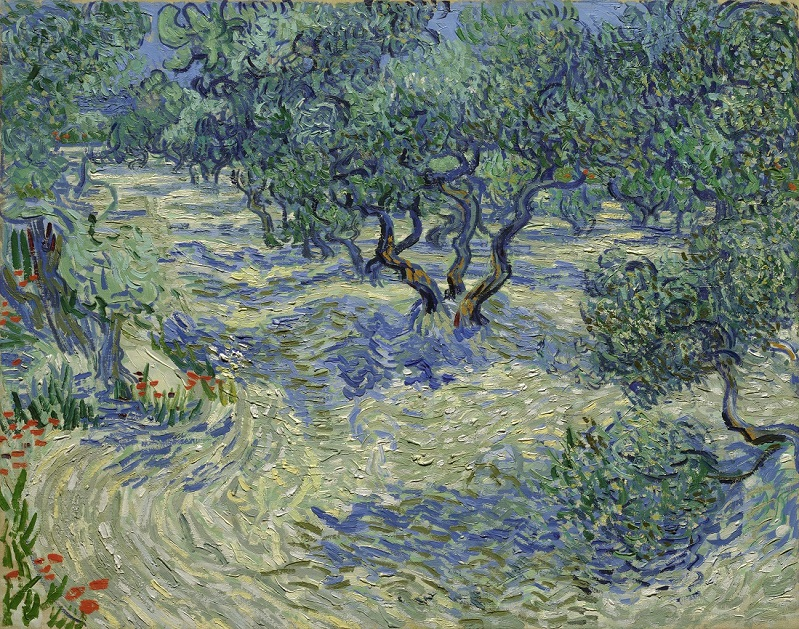

The next purchase would have to wait until 1929, when the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art in Kansas City bought Olive Trees (1889), which had originally been shown at the Armory.

Vincent Van Gogh’s Olive Trees (1889). Image courtesy of Nelson-Atkins Museum.

“It’s a spectacular picture. And it was actually acquired in part because of a petition from a local teacher,” Shaw said. “There was a massive outcry in Kansas City to buy the work for the museum.”

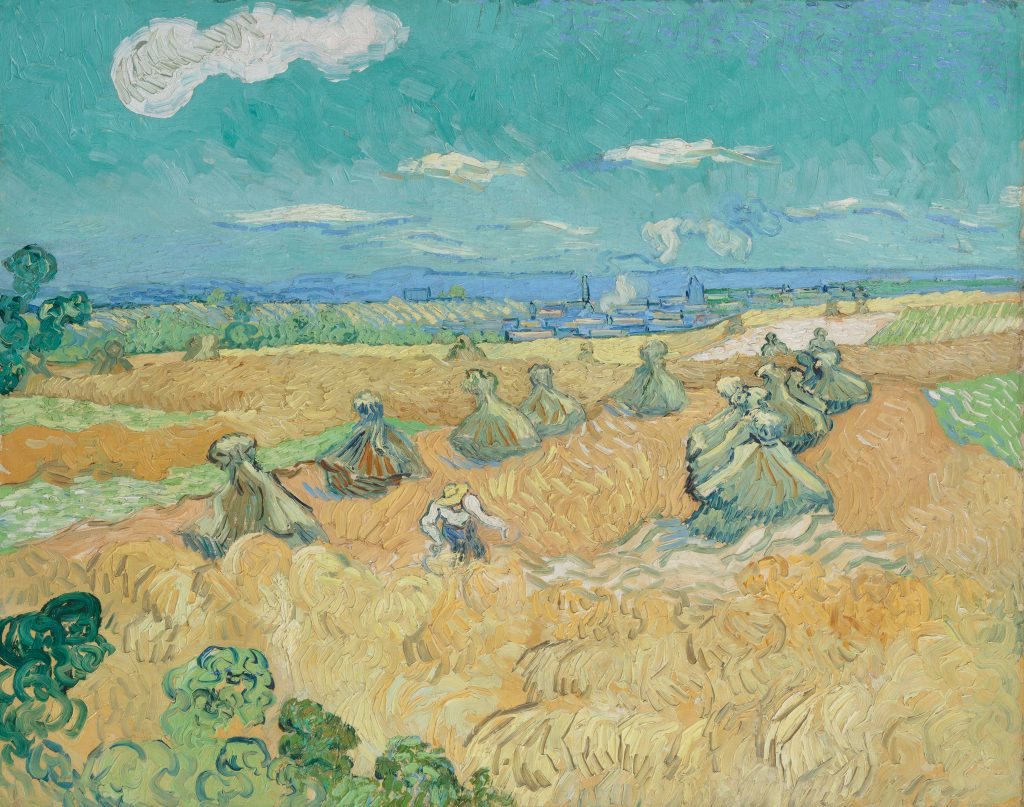

By then, it was clear the Midwest was leading the Van Gogh charge. The Saint Louis Art Museum picked up Stairway at Auvers (1890) in 1932, followed by the Toledo Museum of Art, which bought Houses at Auvers (1890); and Wheat Fields With Reaper, Auvers (1890) in 1934.

“There was a bit of a courageous element to it. The Midwest museums weren’t necessarily so steeped in art collecting traditions and habits of the East Coast,” Shaw said.

These pioneering acquisitions get a dedicated room in the DIA show, with all five of those initial purchases, plus The Bedroom.

Vincent Van Gogh, Wheat Fields With Reaper, Auvers (1890). Collection of the Toledo Museum of Art.

“It’s a really powerful room for me,” Shaw said. “People have said to me that this is what they are going to take away from the show.”

And it’s a moment in the exhibition that represents the turning of the tide, as Van Gogh finally gained acceptance among American audiences. The true flipping of the switch came in 1934 with the publication of Lust for Life, Irving Stone’s sensationalized novel inspired by the artist’s life. A film adaptation starring Kirk Douglas would follow in 1956, with the actor turning to DIA’s self-portrait to help shape his portrayal of Van Gogh.

“In a weird circular way, the painting became famous because of Kirk. Hollywood cemented its status as an icon,” Shaw said.

But before that came the exhibition she considers the art world’s first true blockbuster, Van Gogh’s first solo show at a U.S. museum, which debuted at MoMA in 1935 before traveling to nine other institutions around the country, including the DIA.

The artist’s reputation had slowly grown since his tepid reception at the Armory, appearing in some 50 group shows in the intervening years—including the inaugural exhibition at MoMA in 1929. But in the wake of Lust for Life, over 50 museums begged for a chance to be part of the Van Gogh tour, which continued through 1937 and attracted over one million visitors during its run.

The show returned to MoMA for its final stop, with a fateful addition: Starry Night.

But the famed painting didn’t actually join the collection until 1941, when it became the first Van Gogh at a New York museum. The Met took even longer, finally buying Cypresses (1889) and Sunflowers (1887) in 1949.

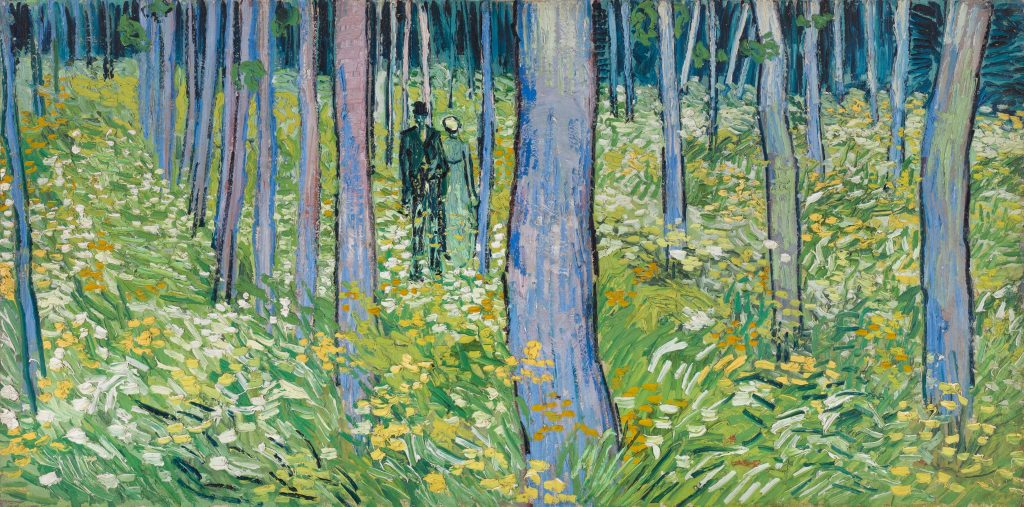

Vincent Van Gogh, Undergrowth with Two Figures (1890). Collection of the Cincinnati Art Museum.

Eschewing a typical chronological presentation of the artist’s career, the DIA instead works off a posthumous timeline. Shaw has reunited 11 works from Van Gogh’s Armory Show appearance, seven of which ultimately landed at U.S. museums, as well as six of the 67 works from the Montross exhibition.

Undergrowth With Two Figures (1890) went unsold at both shows, before Boston collector Gilbert E. Fuller finally bought it in 1929. It appears at the DIA courtesy of the Cincinnati Art Museum, which received the painting as a gift from a later owner. The Armory Show loans, Adeline Ravoux (1890) from Dreier and Self-Portrait (1887) from Quinn, ultimately entered the collections of the Cleveland Museum of Art and the Wadsworth Atheneum Museum of Art in Hartford, Connecticut, respectively.

Those represent just a handful of works on an impressive list of Van Gogh paintings held by U.S. institutions. But there could have been more.

“While America has great Van Goghs, there are some that we didn’t latch onto that we could have,” Shaw said. “And we should have!”

See more works from the exhibition below.

Vincent Van Gogh, Lullaby: Madame Augustine Roulin Rocking a Cradle (1889). Collection of the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston.

Vincent Van Gogh, The Drawbridge (1888). Collection of the Wallraf-Richartz-Museum and Fondation Corboud, Cologne.

Vincent Van Gogh, Poppy Field (1890). Collection of the Kunstmuseum Den Haag, The Hague.

Vincent van Gogh, L’Arlésienne: Madame Joseph-Michel Ginoux (1888). Collection of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York bequest of Sam A. Lewisohn, 1951.

Vincent Van Gogh, Two Peasants Digging (1889). Collection of the Stedelijk Musuem, Amsterdam.

Vincent Van Gogh, Roses (1890). Collection of the National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC.

Vincent Van Gogh, The Dance Hall at Arles (1888). Collection of the Musée d’Orsay, Paris.

Vincent Van Gogh, Mountains at Saint-Rémy (1889). Collection of the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York.

Vincent Van Gogh, Stairway at Auvers (1890). Collection of the Saint Louis Art Museum.

“Van Gogh in America” is on view at the Detroit Institute of Arts, 5200 Woodward Avenue, Detroit, Michigan, October 2, 2022–January 22, 2023.

Source: Artnet News