October 31, 2016

At the Long Museums in Shanghai, an ostentatious billionaire is using art to put China on the cultural map.

“It’s nice to come home to Shanghai,” the Chinese billionaire Liu Yiqian told me one day in February, four months after gaining worldwide notoriety by spending a hundred and seventy million dollars on a painting by Amedeo Modigliani. We had just sat down in his office at the Long Museum West, one of two privately run art museums that he has opened in the city, when his face contorted and a sneeze of atomic force burst out, unhindered by tissue or hand. Liu unself-consciously wiped himself down with a Kleenex, cleared his sinuses copiously, and balled up the tissue, placing it on a glass coffee table between us. Then he returned to the subject of his home town: “It might not have a long history, this city, but it is a place made by immigrants, for immigrants. We are exposed to so much from everywhere that people here have to adapt.”

Liu’s office is modest. Cold winter light entered through a window that looked onto a shabby courtyard. The room was sparsely decorated, and the most personal touch was a framed calligraphy scroll whose characters read “Patience, perseverance.” Liu had just got back from Wuhan, where he is building another branch of the museum, and he seemed tired. Wearing clothes that were quietly expensive—a black linen jacket, black pants, and black, woven slip-ons—he slumped on a black leather couch. His face showed a day’s worth of stubble and he smoked continually—Chunghwa, the cigarettes that Chairman Mao favored. “It’s a Shanghai brand, so I’m used to it,” he said, adding that he had smoked since boyhood: “When I was very young, I used to roll up toilet paper and copy the adults by sticking that in my mouth.”

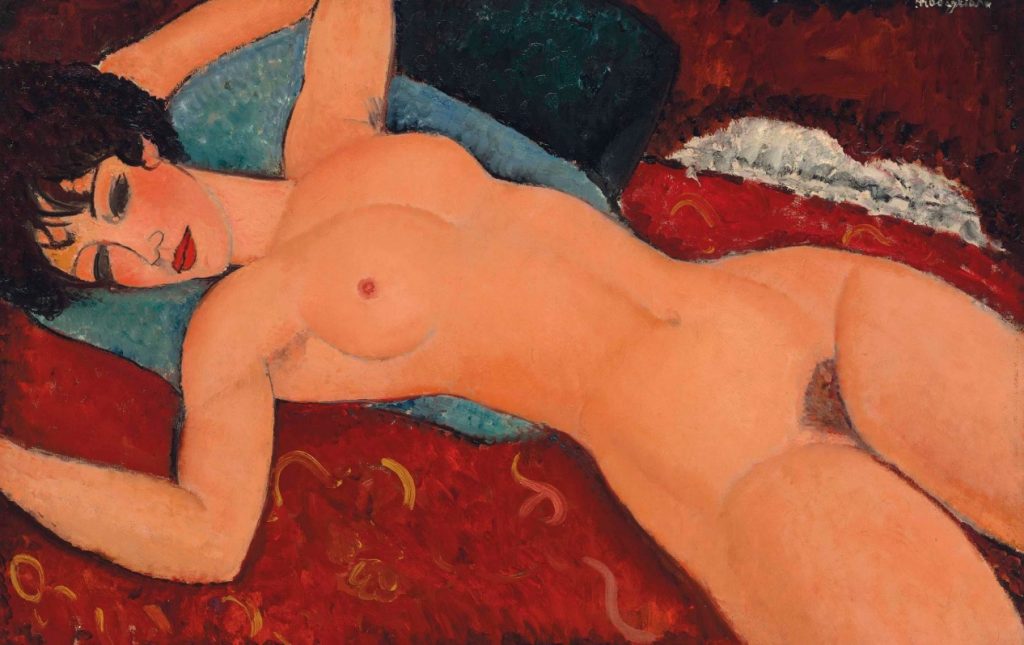

The Long Museum West (long means “dragon” in Chinese) opened in 2014, on a scenic stretch of land on the western shore of the Huangpu River. The Shanghai government had offered a generous discount on the property, in an area that was once a manufacturing hub but is being transformed into a “cultural corridor” intended to rival New York’s Museum Mile and London’s South Bank. The building is impressive, designed, in an industrial international style, by the young Chinese firm Atelier Deshaus. Inside, a series of colossal half-arches in rough concrete interlock, as if in an M. C. Escher print, giving the space an unfixed, exploratory feel. The Modigliani—a dark-haired reclining nude seen against a flame-colored background, finished in 1918—will be the museum’s centerpiece, but the bulk of its collection is contemporary art from around the world. The museum is Liu’s second; the first, the Long Museum East, a ten-thousand-square-metre granite monolith east of the river, opened in 2012 and contains Chinese antiquities and works by prominent contemporary Chinese artists. A third location opened in Chongqing earlier this year, and the Wuhan branch will open in 2018. Together, the museums, which are run by Liu’s wife, Wang Wei, house China’s largest private art collection.

Long Museum West Bund © Wu Junze

Liu is the forty-seventh-richest person in China, with an estimated fortune of $1.35 billion. An early investor in China’s nascent stock market, in the early nineties, he has since diversified into construction, real estate, and pharmaceuticals. He is fifty-three and has bristly, slightly graying hair, watchful eyes, and a paunch that suggests the banquet diet of beer and grain liquor that is an inextricable part of Chinese business culture. Liu speaks in a raspy voice, and his demeanor is brusque. He almost never makes eye contact. Often, he seems barely to hear questions, and his answers, when they come, are less like responses than like peepholes into some fleeting train of thought. Occasionally, when an idea interests him, he cocks his head, and his mouth forms a lopsided grin.

Powerful Chinese businessmen tend to be circumspect and wary of attention, because their success depends on not attracting government disfavor. Liu, however, is known for a brash, flamboyant style. After the Modigliani purchase—which exceeded by a hundred million dollars the record paid for a work by the artist—there was a flurry of international news stories in which Liu, who was little known outside China, spoke with outrageous casualness about the painting, noting that it was “relatively nice,” at least compared with other Modiglianis. Now, however, he talked as if he’d found the attention unsettling, and seemed unsure whether Western fascination with his humble origins—he started out as a market vender, and later drove a taxi—connoted respect or something else. Before our meeting, his assistant warned me on no account to mention an article in which Liu called himself a tuhao, a term meaning “uncouth and wealthy,” and applied derisively to those who have risen from nothing in China’s hyperkinetic economy. But among Chinese Liu takes a certain pride in playing the equivalent of the Beverly Hillbillies—an Everyman who has suddenly got wise to the cultural cachet of art.

Amedeo Modigliani (1884-1920). Nu couché.

Liu began collecting as early as 1993, but he first drew notice in 2009, when he paid more than eleven million dollars for a wooden Qing-dynasty throne carved with dragons. Since then, he has acquired a reputation for paying record-breaking amounts—forty-five million dollars for a six-hundred-year-old Tibetan silk tapestry, nearly fifteen million for a Song-dynasty vase, and thirty-five million for an ink landscape by the twentieth-century artist Zhang Daqian.

When I mentioned the Modigliani, Liu let out a dry laugh. “Here’s the deal with the Mudi,” he said, using an abbreviated Chinese approximation of Modigliani’s name. “It’s not just his art but his life. Every object has its story. Maybe if he hadn’t flung himself out of a window at thirty-six, his work wouldn’t be anywhere in the millions.” Among Western dealers, Chinese buyers are known for being more interested in an art work’s associations than in its aesthetic properties. But Liu had his facts tangled: Modigliani died at thirty-five, from tuberculosis; it was his mistress who committed suicide.

Liu’s extravagant hobby is the subject of considerable fascination in China, and is interpreted variously as a financial investment, a publicity stunt, a patriotic bid for the world’s attention, and an act of pure ostentation, such as one might expect from a tuhao. Liu told me that he thinks the museum fills a gap in China’s cultural life. Until recently, the country had few museums, and most of them were barely worthy of the name. “The mission of the Long Museum is to educate the Chinese public, and to present quality work that is on a par with other state-of-the-art museums around the world,” he said. He spoke of giving China a cultural prestige commensurate with its wealth: Western museums are full of Chinese art, but China has few Western art works of the calibre of the Modigliani.

Liu’s buying spree is one of many developments that are turning Shanghai, China’s most Westernized city, into a global center for art. But it is also a demonstration of China’s brute purchasing power. “If a Westerner bought these Western masterpieces, people would think it was very normal,” he told me. “But, because they were bought by an Asian, and not just a Japanese but a Chinese person—” He looked up, his eyes full of impish pride. “After all, isn’t that why you are here?”

Liu Yiqian was born in 1963, to Shanghai factory workers who had the good fortune, in the view of Chinese society, of having three sons and the misfortune of having little to give them in the way of material comfort. Liu’s role model was his maternal grandfather, a schoolteacher from an adjacent province who later became a lawyer. “He was my first teacher, the person who instilled in me a rudimentary sense of the world,” Liu has written, in a kind of diary-blog that he keeps on the Chinese social-media app WeChat. Liu’s fondest childhood memories are of sitting on his grandfather’s lap as the old man told him ancient fables or read to him from the cheaply produced, garishly illustrated Maoist storybooks of the time.

These books, part of a canon of Communist art works known as “red classics,” have recently become collectors’ items, and the Long Museum West has the largest private collection of them, assembled by Wang Wei. Liu’s favorite story was “The Cock Crows at Midnight,” about a greedy landowner who tricks his farmhands into rising early by crowing like a rooster at midnight. Eventually, one of them figures out the ruse, and, pretending to mistake the errant cock for a thief, gives him a good beating. A year ago, the museum mounted an exhibition on the story, and Liu wrote about it on WeChat: “When I read this story as a kid, everyone knew the farmhand was the hero and the landowner the villain. But now, thinking it over, I wonder, Didn’t the landowner have to wake up even earlier than the farmhands to pretend to crow like a cock? So I have to ask myself, ‘Am I now the landowner or the farmhand?’ ”

In 1966, when Liu was two years old, the Cultural Revolution began, plunging the nation into chaos. A band of teen-age Red Guards stormed the family home, searching for anything that could be deemed counter-revolutionary. They found a broken fluorescent light fixture in a battered armoire, and Liu’s grandfather was accused of hiding a bomb. He was arraigned at one of the infamous “struggle sessions,” in which counter-revolutionaries were forced to admit their wrongdoing. His punishment was to perform three days of public contrition, standing in a ninety-degree-angle bow.

When I asked Liu about the effect of the Cultural Revolution on his childhood, he claimed not to remember much. “What’s the use of thinking about that stuff?” he said. But on WeChat he is less guarded. “I don’t have many happy childhood memories, but that particular incident is etched into me,” he wrote. “Even as a toddler, I knew it wasn’t a bomb. Watching my grandfather humiliated and led away by a bunch of children filled my young heart with enduring hate, vengefulness—that and the desire to permanently play hooky.” Liu made a habit of running away from home.

In 1977, when he was fourteen, Liu dropped out of school. “You guys continue reading your books,” he told his classmates. “I’m going off to make money.” His timing was perfect. The next year, Deng Xiaoping took over as the country’s leader, and instituted a market-based overhaul of China’s moribund economic system. Liu went to work for his parents, who had opened a market stall selling leather bags in Yuyuan Gardens, the most popular tourist destination in Shanghai. Such an accessory would have been denounced as bourgeois frivolity only a few years before, but now fashion merchandise signified status.

Liu remembers cutting up sheets of leather with huge shears to make pants, shoes, and bags, an activity that has left him with a pinched nerve in his right thumb. “There was never a day we didn’t work,” he recalled. “Even on all the days of the Chinese New Year, from morning until night.” He was a fast worker, and made more than a hundred yuan daily—at a time when that was the monthly budget of the average family. In three years, he entered the ranks of “ten-thousand-yuan earners,” as the young winners in Deng’s economic system were known.

One day, Liu found himself waiting two hours for a taxi at the Shanghai train station. This gave him an idea, and, at the age of twenty-one, he started a taxi business, buying two cabs and driving one of them himself. “I knew I couldn’t be the only one wasting this much time on the curb,” he told me, hunching forward in a gesture of impatience. “It wasn’t even a decision.”

Liu’s entrepreneurial instinct served him well in the volatile economic climate of the early nineties. On a trip to Shenzhen, where the government had established a so-called Special Economic Zone to test market-oriented policies, Liu ran into a former classmate who explained a fledgling concept called the stock market. For the first time, China’s state-owned companies were issuing shares, but these were little understood by the general public. For a hundred yuan each, Liu bought a hundred shares of the company that owned the market where his parents rented their stall. Within two years, each share was worth ten thousand yuan. Liu had become a millionaire, one of the few in China, at a time when the concept struck ordinary citizens as an inconceivable novelty.

Today, almost all of China’s mega-rich enjoy some relationship with the government, and Chinese bloggers speculate endlessly about Liu’s ties to the political élite. Perhaps because of this, Liu, like many Chinese tycoons, is careful to seem modest when speaking about his success. When I asked him what talents had enabled him to rise, he waved the question away. “My business career must be looked at against the background of China’s economic growth,” he said matter-of-factly. “China experienced a lot of change and generated a lot of wealth. There’s luck there and, of course, some diligence. That’s how my generation was created.”

Liu’s WeChat posts, though, reveal how the vertiginous trajectory of his life continues to preoccupy him. “I spent my youth betting on tomorrows,” one entry reads. “But if I had finished school how differently would my life have turned out?” The irony of his life now is that he is frequently mistaken for someone unimportant. “Forgot the security code to my own apartment”—he owns hundreds of apartments in Shanghai. “Security guard thought I was a random loiterer and asks suspiciously who I am here to see.” When his Shanghai museums were being built, he liked to sit outside eating lunch with the construction workers, and friends of his told me that he goes unrecognized at museum openings. Squatting by the entrance, smoking, he is taken to be a janitor.

Liu’s generation grew up in what he refers to as Old Shanghai. In the days before economic liberalization brought some measure of prosperity to China’s big cities, Shanghai was a sleepier, more insular town, where everyone spoke Shanghainese, rather than Mandarin. The city of Liu’s youth had its origins in the eighteen-thirties, when the British East India Company tried to establish a trading post on the banks of the Huangpu River. Resistance led to the first Opium War, which the British won, and Western powers set up a series of “concessions,” districts that were not governed by Chinese law. Hotels, villas, cathedrals, racecourses, and theatres quickly sprang up, and the city was alternately hailed as the Paris of the East and lambasted as the Whore of the Orient.

The very qualities of adaptability and openness that allowed Shanghai to flourish also made—and still make—the city the focal point of China’s uneasy encounter with the West. Today, more than a quarter of the foreign nationals in China live there, and Shanghai natives like to think of themselves as more sophisticated than their compatriots in other cities. As the mid-century novelist Eileen Chang—the city’s most famous writer—once put it, “The people of Shanghai have been distilled out of Chinese tradition by the pressures of modern life. They are a deformed mix of old and new. Though the result may not be healthy, there is a curious wisdom to it.”

If you wander through central Shanghai, this mixed heritage is manifest on every street corner. The old trading houses and apartment buildings of the Bund, an iconic riverfront promenade, wouldn’t look out of place in a Western capital. Elsewhere, you can still find narrow brick alleys of shikumen—a hybrid of traditional courtyard dwellings and Western town houses—which were built in the eighteen-sixties to house a booming population of Chinese workers.

Early in my visit to Shanghai, I met Leo Xu, a young gallerist, who took me to the Jin Jiang Hotel, in the heart of the old French Concession. Like many businesses in the neighborhood, the Jin Jiang, which was established in the nineteen-thirties, operates as a pastiche of the city’s cosmopolitan heyday. We walked down a wood-panelled corridor, lined with photographs of svelte, cheongsam-clad movie and cabaret stars, to the hotel’s ornate dining room. Service was old-fashioned and deferential, and swing music drifted from hidden speakers. Without glancing at the menu, Xu ordered braised duck and pickled beets, classic dishes that typify the sweet, subtle flavors of the city’s cuisine.

As we ate, Xu told me about Shanghai’s gallery scene and its collectors. Francis Bacon, for instance, doesn’t sell. “The Chinese don’t see themselves in the work,” he said. “Chinese collectors need to be able to relate to it and to feel that it has at least a little relevance to how they live or what they know.” They prefer either traditional Chinese ink paintings or works by current art-world stars such as Antony Gormley, Damien Hirst, and Olafur Eliasson. Name recognition is paramount. “If buyers are putting down such a large sum, they want blue-chip artists, someone everyone knows,” Xu said.

Xu was eager to talk up the city’s artistic importance. He claimed that it had surpassed Beijing, which is generally held to be the center of the Chinese art world, and that its immigrant history made it more open than other Chinese cities. “Beijing has traditionally focussed on art that is state-sanctioned,” he said. “Shanghai, on the other hand, and especially in recent years, is about culture and the varieties of individual experience.”

China’s earliest museums were established in Shanghai, by Europeans, to serve European ends. The first of them, the Xujiahui Museum, was founded in 1868, by a French Jesuit priest and zoologist who combined his missionary work with collecting animal and plant specimens from the Yangtze Delta. Once missionaries realized that exhibiting the wonders of the natural world made the local population more enthusiastic about Christianity, similar museums followed. It was in such museums that the Chinese public first encountered maps, and saw China as a physically demarcated territory, rather than as the entire world, as many had supposed it to be.

Yet the Chinese élite, traditionally the patrons and collectors of art, had no interest in entertaining or educating the masses. After the Communists came to power, the arts were repurposed as a political tool and subsumed into the Department of Propaganda. But in the early nineteen-eighties the government began to see museums as a way of advertising the vitality of Chinese culture, and they spread across the country. The trend has intensified since 2012, when Hu Jintao, then China’s President, announced a strategy to build a “great nation of culture.” In 1949, China had only twenty-one museums. There are now more than four thousand.

One afternoon, I met Li Xiangyang, who was the head of the Shanghai Art Museum from 1993 to 2005, and has been a close observer of the city’s evolving relationship with art. Now in his sixties and semi-retired, he does traditional ink paintings, and has published a memoir recounting his life in the museum world. During the Cultural Revolution, when Li was in his late teens, he got a job as a propaganda illustrator, churning out pictures of factory workers and of farmers toiling in wheat fields. “I wasn’t an artist,” he said. “Nobody called himself that in those days. There wasn’t even regular school, never mind art school.” His curatorial career began by chance, when a local Party official, with no training in art, decided that Li should run the museum. The project had few resources and no defined mission. “When I started, we knew very little about Chinese art history and almost nothing about Western art,” he said.

Despite the museum’s impressive-sounding name, it was comically ramshackle, with no permanent collection. “Do you know what our museum space was?” Li said. “The second floor of a bank, which local hobbyists rented occasionally in order to exhibit their drawings to one another.” Few members of the public ever visited. “The worst part was that I was in charge of earning my own salary, and also maintenance fees for the museum,” he said, with a snort of laughter. “So if I didn’t rent out the space enough times a month I didn’t get paid, and neither did my staff!”

Li learned on the job. He managed to make fact-finding trips to Japan, Singapore, and Europe. In Germany, he was astonished to see volunteer docents: the idea that anyone would work in a museum for nothing seemed fantastical. He recalled the thrill of visiting the Louvre for the first time: “There were so many things I wanted to bring back to this city, like a farmer who wants to bring back as many seeds as possible to his own field.” For Li, the audio guides were as exciting as the masterpieces on display.

In a culture with no tradition of museums, the government’s sudden demand for many more of them was hard to satisfy. “Modernization! Soft power!” Li said, in a singsong voice—catchphrases, respectively, of the Deng and Hu Jintao administrations. “But when I was in the job few people even knew the word ‘museology.’ ” Another Shanghai museum director used an analogy to describe the predicament. “A tuxedo, like a museum, is expensive and has many pieces,” he said. “You have the shirt, the bow tie, the vest, the jacket, and more. But so few Chinese have even seen a tux that the leaders are just trying to familiarize the people with the garment. And, rather than buying every single piece, maybe we conserve some fabric and sew shirt collars onto the vest instead.”

Ivisited the Long Museum West early one Sunday morning. A pair of Japanese tourists and some Danes holding guidebooks waited uncertainly in the entrance lobby. From the exhibition space beyond, a woman in jeans peered out and yelled at a security guard, “Why did you open the door?” The museum wasn’t open yet.

Fifteen minutes later, I stood in the main hall. The vaulted ceilings rose so high above the gallery walls that the whole floor had the feel of a single palatial room. The galleries were devoted to contemporary art—Chinese antiquities are in darkened rooms in the basement—and the first piece that caught my eye was a cartoonishly sculpted bright-yellow dog with neon-green polka dots. His name was Chan-Chan, and he was the creation of Yayoi Kusama, the Japanese conceptual artist. A few feet away was a large robot constructed entirely from vintage television sets, by the Korean-American video artist Nam June Paik, and “The Embodiment of Tree,” by the Japanese sculptor Ikki Miyake—a wooden figure of a woman with her hands stretched upward above her head. Individually, the pieces were interesting enough, but their placement seemed haphazard. Along the walls, paintings of various sizes jostled one another.

Liu, in his WeChat diary, loves to post photographs of his museums when they are packed, with a line snaking out the entrance, like, as he puts it, “a great big dragon.” He sees the museums as a means not only of educating the public but also of tempering materialism. “Since the standard of living has improved, more people are concerned about spiritual satisfaction,” he said. “Culture, which we neglected for a while, we are now picking up again as a people.”

“There’s no model for the kind of museum he’s building—nothing of its scale and ambition,” the New York gallerist David Zwirner told me. “He is a trailblazer, which is probably as daunting as it is exhilarating.” Marion Maneker, an art-market analyst, compared Liu’s undertaking with current attempts to assemble world-class collections in the United Arab Emirates. In both cases, funds are practically limitless, but there is not yet a fixed sense of art history or of the role of museums. Copying Western models, Maneker suggested, could take one only so far. “There is no such thing as the platonic ideal of a great, encyclopedic museum,” he said. “Even the Louvre and the Met were products of their time and a certain amount of luck.” If Liu’s museum empire is to become great, he said, “it needs to draw connections, be greater than the sum of its parts, tell a story.”

Liu’s museums face other challenges, too. Everyone I spoke to mentioned financial sustainability. Philanthropy is not well-established in China—until recently, there was no tax incentive to donate to nonprofit institutions—and though the government sometimes provides funds for construction, it contributes nothing to operating expenses. Liu had told me he hoped that the Long Museums would be a lasting feature of the Chinese cultural landscape, but the volatility of the domestic stock market casts doubt on the permanence of anything built on a private fortune.

A large number of wealthy Chinese, Liu among them, have recently come to dominate the market for Asian art—much of which was plundered by the West. (unesco estimates that 1.6 million Chinese artifacts left the country illegally in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries.) The government has become active in petitioning for restitution, and many Chinese collectors regard it as their patriotic duty to bring back important items. Liu’s purchases fit this trend, but, as on other subjects, he is careful not to express resentment about the loss of heritage. “When we are young, we are indoctrinated to believe that the foreigners stole from us, but maybe it’s out of context,” he told me. “Whatever of ours they stole, we can always snatch it back one day. The laws of the market always rule.”

Many collectors keep their purchases anonymous, but Liu broadcasts his acquisitions, something that even some of his close friends initially found offputting. Zhu Shaoliang, a prominent collector of Chinese antiquities, told me that when he met Liu, in 2009, at an auction, he thought he was “aggressively boastful.” Zhu went on, “He was making these wild claims about ancient Chinese art, and it made me so angry. I thought, This person is just so uneducated!” But Zhu and Liu eventually became friends, and, over the years, Zhu has advised Liu on purchases; in 2014, he vouched for the authenticity of an ancient scroll in Liu’s collection that was suspected of being a forgery. “It takes a while to get to know him, but Liu learns fast, and he is both decisive and bold,” Zhu told me. “In some ways, he buys art the way he conducts business.”

Liu’s attitude toward running a museum is unconventional, and it troubles many people in the art world. The security arrangements are widely held to be inadequate for such a valuable collection, and other operations that are vital in most museums, such as P.R., are all but nonexistent. “They don’t spring for that kind of thing, because they think it’s unnecessary,” Jia Wei, a former auctioneer, who used to work with Wang Wei, Liu’s wife, told me. “They both want to do everything themselves.”

Alexandra Munroe, the head of Asian Art at the Guggenheim Museum, has visited the Long Museum on a number of occasions and has been shocked by what she sees as insufficient professionalism. “They are lacking in the absolute fundamentals of how to handle art,” she told me. Walking through the antiquities section of the Long Museum West, she noted, with dismay, that fabric cords, which are attached to scrolls for the purpose of tying them when they are rolled up for storage, were left dangling in front of the art. “It’s the equivalent of walking into a museum here and seeing a van Gogh hung upside down,” she said. “It’s about custodianship. Just because you own the art and the museum doesn’t mean that you get to disrespect it.”

Liu’s treatment of some of his most precious art works has enhanced an impression of cavalier ignorance. In 2014, he spent more than thirty-six million dollars on a fifteenth-century porcelain cup decorated with a chicken motif, which had been owned, in the eighteenth century, by the famous Qing-dynasty emperor Qianlong. Liu publicly sipped tea from the artifact—scandalizing the art world and cementing his reputation as a cheeky eccentric. “Emperor Qianlong has used it; now I’ve used it,” he explained afterward. “I wanted to channel his spirit.” The next year, in a hotel suite in New York, he celebrated the purchase, for five million dollars, of a twelfth-century Tibetan bronze of a seated yogi by stripping down to his underwear, mimicking the statue’s lotus pose, and circulating pictures of the yogi and himself on social media.

Ming Dynasty ‘chicken cup’ smashes record in $36 million sale at Sotheby’s in Hong Kong.

On my last night in Shanghai, I accompanied Leo Xu and a few of his friends to what they described as the “hottest art opening of the season.” We got in an Uber and drove toward the neon of the city’s commercial center. The car pulled up in front of a crescent-shaped courtyard full of signs that did not immediately suggest artistic endeavor: Burberry, Bally, Dolce & Gabbana. Around the perimeter of the courtyard were upscale gift shops, staffed by tuxedoed salesmen. In a central atrium, open to the sky, complicated-looking pieces of jewelry lay on silver platters beneath glass domes. It was unclear if they were on display or for sale.

K11, Hong Kong. Source: Vn Trip.

The venue, which opened in 2013, is called K11, and its aim is to combine the functions of art museum and shopping mall. In the art space, which is downstairs from the courtyard, I wandered through galleries of paintings, performances, and installations by fifty-five young artists. Next to each work was a QR code, which you could scan with your phone to get a statement by the artist. Attendants glided around, silently distributing and collecting audio guides. The galleries were much more crowded than the ones I’d seen at the Long Museum. In one room, people clustered around a figure in a red basketball jersey. It turned out to be a statue of the Shanghai-born basketball star Yao Ming, shrunk to about five feet. (Yao is seven and a half feet tall.) I scanned the QR code and learned that the artist had hoped that shrinking China’s most famous giant would “ridicule reality and authority.”

A young man in sweatpants and a camel-hair coat sauntered in, surrounded by assistants holding clipboards and iPads. Leo Xu nudged me: “That’s Adrian Cheng, the owner.” Cheng is thirty-seven and comes from a Hong Kong real-estate family with vast holdings throughout China. Educated at Taft and at Harvard, Cheng spends his time shuttling between Hong Kong and the mainland, visiting Europe every month and New York twice a year. He described the idea of K11 to me with smooth, practiced fluency. “In China, people don’t go to museums,” he said. “They go shopping. The Chinese love luxury. But the concept of luxury is evolving here on the mainland. It used to be fast cars and designer clothes. Now the focus is shifting to culture.” As a business strategy, the use of art to lure curious customers seemed to be working. Philip Tinari, an American curator who directs a contemporary art center in Beijing, told me about a K11 Monet show in 2014. “The lines looped around the block, because Monet is one of the five Western artists Chinese people have heard of,” he said. “When people are bored in line, what do they do? They shop. It’s brilliant.”

In the middle of one room at K11, there was a plain white wall, guarded by a uniformed attendant. Next to a slit in the wall was a label that said “Please insert one yuan coin.” On the other side of the wall was a dispenser with instructions to withdraw a one-yuan note. A line of visitors pushed coins in and exclaimed as bills came out. The piece, “Past Opportunity,” was by Liu Chuang, a young artist represented by Leo Xu’s gallery. Xu explained that Shanghai’s many vending machines dispense coins but that taxi-drivers and other venders prefer bills: “They cuss you out whenever you give them a coin.” The symbolism was unavoidable. In the middle of K11’s fusion of culture and commerce was an art work that changed money into money, leaving no one richer but everyone feeling better off.

It was getting late, and the crowd had thinned. I started talking to the attendant, who told me that she and her husband had moved to Shanghai six years earlier, in search of work. She’d never been in a museum until she started working in one. “I’ve been standing here handing out coins for three hours and I still don’t get this thing!” she said, laughing. Xu took a coin from his pocket and said, “This tiny gesture, to which most people attribute absolutely no significance, says something about Chinese economic trends over the past few decades. It shows how in the course of change there are these opportunities, big and small. And, once you convert something to something else, you usually can’t go back.” Xu inserted his coin into the slot and when a yuan bill emerged he motioned to the woman to keep it.

Xu and his friends hoped that Liu and his wife, who know Cheng and are regulars at Shanghai art openings, might make an appearance. But they were in Hong Kong. Later, Liu posted on WeChat a picture of a stock certificate from the early days of the Shanghai stock market. Underneath, he wrote that he had mislaid a box of these certificates when moving house. “Someone must have found them worth keeping, because an auction house here in Shanghai just began selling them this year,” he wrote. “I can still see my address, my own handwriting, and the places where I blotted out a misspelling.” In another post, he noted with satisfaction, “Today, several boxes’ worth of them will fetch quite a price.” In the art market, the relics of Liu’s rise were becoming a commodity.

Source: The New Yorker, Financial Times, Christie’s, Sotheby’s