An overview of the French painter who paved the way for Cubism and Fauvism, illustrated with highlights from the Museum Langmatt on offer at Christie’s this November

1 | He grew up with Émile Zola

Paul Cezanne (1839-1906), Quatre pommes et un couteau, c. 1885. Oil on canvas. 8¾ × 10¼ in (22.2 × 26.1 cm). Estimate: $7,000,000-10,000,000.

Offered in 20th Century Evening Sale on 9 November at Christie’s in New York.

Paul Cezanne, whose innovative Post-Impressionist paintings would pave the way for 20th-century Modernism, was born in Aix-en-Provence. He was a childhood friend of Zola; who would become the most prominent French novelist of the late 19th century.

Whilst studying together at the Collège Bourbon with Louis Marguery and Jean-Baptiste Baille they formed a close-knit group they nicknamed Les Inséparables. Cezanne defended Zola from bullies in the schoolyard, and one day Zola thanked him with a basket of apples. The moment had a great impact on Cezanne, and the apple would become a favoured subject of his.

The two continued to support each other until 1888 when Zola used him as the basis for the failed artist character in his novel L’Œuvre, putting a strain in their relationship.

2 | He had to fight to be an artist

Cezanne’s father didn’t initially support his son’s artistic career. He wanted him to study law and manage their family-owned bank.

After two years at the law school of the University of Aix-en-Provence, Cezanne dropped out. Zola was then living in Paris and urged him to join the community of avant-garde artists and writers there. With his mother’s support, Cezanne convinced his father to let him go to the capital to study painting.

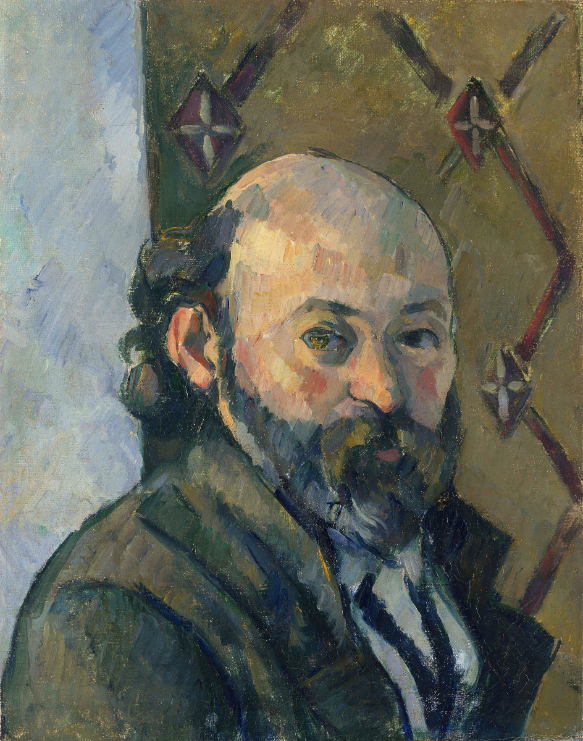

Paul Cezanne, Self-portrait, c. 1880. The National Gallery, London.

3 | Pissarro and Manet influenced him

It was at the Atelier Suisse that Cezanne met Pissarro, nine years his elder, in 1865. They developed a close relationship and began to paint together outside in villages outside Paris for the next 10 years. Although their painting styles differed — one onlooker described ‘Monsieur Pissarro, when he painted, dabbed, and Monsieur Cezanne smeared’ — they were both ambitious, unorthodox painters.

With little chance of success in the state-sponsored salons, they both responded by embracing their independence. This time marked a major turning point in Cezanne’s style. It pulled Cezanne out of his Dark Period and into plein air, as he turned to the vibrant colours and intricate brushstrokes of Impressionist-style landscapes.

Paul Cezanne, A Modern Olympia, c. 1873-74. Musée d’Orsay, Paris.

By contrast, Edouard Manet was considered by many to be the leading Modern artist of the time, and this spurred Cezanne into competitive action. Manet’s flat style of painting, and his readiness to paint urban scenes of modern life led Cezanne to similarly push against the bounds of artistic tradition. In 1865 Cezanne’s submission had been rejected from the Salon, in favour of Manet’s Olympia. Nearly a decade later, Cezanne offered a retort in his painting A Modern Olympia — it caused an even greater scandal.

4 | He developed his own painting method

Cezanne’s ‘ideal of earthly happiness’, according to an interview in the late 1890s, was to create his own belle formule, or ‘beautiful way of painting’.

Whilst he was painting in the same milieu as the Impressionists, he was developing his own unique technique. In his early years, he would use a palette knife to block in large areas of colour in a flat, unmodulated manner. As his career went on, he added repeated small parallel or perpendicular strokes of paint in changing gradations of colour to build up forms. This technique of small brush strokes was similar to that of his fellow Impressionists, but it lacked their impulsivity, since he was known to spend hours on a single line.

Paul Cezanne (1839-1906), La mer à l’Estaque, c. 1878-79. Oil on canvas. 15½ × 18½ in (39.2 × 47 cm). Estimate: $3,000,000-5,000,000.

Offered in 20th Century Evening Sale on 9 November at Christie’s in New York.

The artist’s analytical approach to painting was another step away from the Impressionists. Following the onset of the Franco-Prussian War, Cezanne left Paris for the South of France in 1886. He began to paint landscapes in and around Aix and of L’Estaque, near Marseille. Here he developed his theory that everything in nature could be reduced to its primary geometrical form of sphere, cone, cube or cylinder.

In his painted world, apples were spheres, houses were cubes, and trees were combinations of cylinders. His compositions were highly structured, with a focus on geometrical shapes. These shapes would often be slightly blurred, reflecting how he had studied them from various angles.

5 | Many consider him the father of modern art

At the beginning of his career, Cezanne went through his ‘Dark Period’ (1861-1870). His works from this time are characterised not only by their dark palettes with dramatic tonal contrasts but by the thick layers of pigment applied with a palette knife, which worked together to communicate emotions beyond the subject itself. For example, in Antoine Dominique Sauveur Aubert (born 1817), the Artist’s Uncle, the harsh black outline of the figure’s form and equally harsh black strokes defining his features create a sense of repressed, violent fury. This technique, which reflected the psyche of the artist as well as the subject, opened the door for modern Expressionism.

Paul Cezanne (1839-1906), Fruits et pot de gingembre, 1890-1893. Oil on canvas. 13⅛ × 18⅜ in (33.4 × 46.6 cm). Estimate: $35,000,000-55,000,000.

Offered in 20th Century Evening Sale on 9 November at Christie’s in New York.

Cezanne’s analytical approach, whereby he identified everything he saw with its primary geometric form, and the way he played with linear perspective and three-dimensional space — flattening objects in order to focus on their surfaces and viewing them from different angles — laid the foundation for 20th century Cubism.

The way Cezanne broke pictorial traditions of three-dimensional space, flattening shapes to focus on their colourful surfaces, and built form from colour also inspired the Fauvists, who rejected three-dimensional space in favour of a new type of space defined by planes of colour.

Cezanne’s work became the bridge between 19th-century Impressionism and 20th-century Cubism, Fauvism, Expressionism, and later Abstract Expressionism.

6 | He was an artist’s artist

Cezanne didn’t have much mainstream success as an artist until the final years of his life, but Ambroise Vollard — an important dealer and patron of avant-garde artists in Paris — was an early supporter. He was instrumental in raising his profile from that of an unknown artist to a highly sought-after painter.

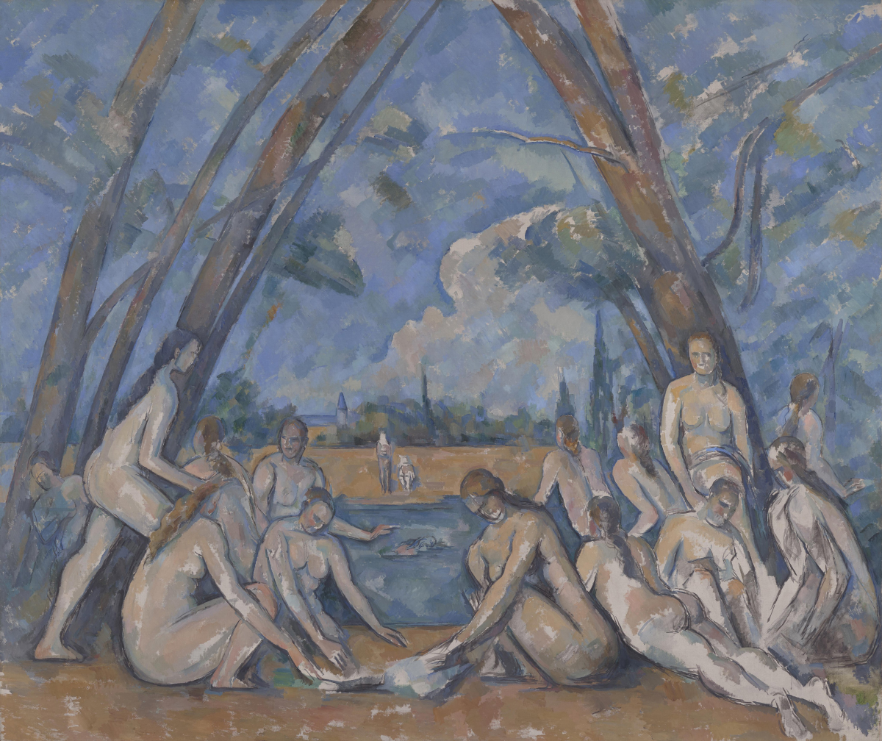

Paul Cezanne, The Large Bathers, 1900-1906. Philadelphia Museum of Art.

Cezanne’s main admirers and collectors were fellow artists. Monet first encountered Cezanne’s work in 1863, and he made no effort to hide his unfettered admiration, calling him ‘the master of us all’. His personal art collection featured more works by Cezanne than by any other artist — 15 in total, with three hanging in his bedroom. The other Impressionists — Gustave Caillebotte, Pierre-Auguste Renoir, Edgar Degas, and Camille Pissarro — all collected his work too. Paul Gauguin even used to take one of his favourite Cezanne paintings to a nearby restaurant to show it off.

This admiration was equally strong among the next generation of artists, including Picasso and Matisse. Pablo Picasso went so far as to buy the land that contained Cezanne’s most important motif, Mont Sainte-Victoire.

7 | Cezanne pushed the boundaries of still life painting

Many critics considered still life paintings to be less imaginative than portraits and landscapes, but Cezanne undermined that assumption. The genre gave him the time and space to fully develop his slow-moving, analytical technique, which was part of his larger, lifelong project to capture empirical truth in painting. He once said, ‘painting from nature is not copying the object. It is realising one’s sensations’.

As a result, his still lifes feel simultaneously ‘alive’ and ambiguous. An expert at conveying the sculptural weight and volume of everyday objects by layering tiny brushstrokes in complementary colours, he would also constantly rearrange these objects, capturing them from multiple viewpoints.

Paul Cezanne (1839-1906), Bouilloire et fruits, c. 1888-1890. Oil on canvas. 19⅛ × 23⅝ in (48.6 × 60 cm).

Sold for $59,295,000 in The Impressionist and Modern Art Evening Sale on 13 May 2019 at Christie’s in New York.

For example, the tablecloths in his paintings seem to rise up to meet the viewer and display the fruits upon it without any visible means of support. It often looks like his apples, orange and lemons could roll off the table, which is angled upwards to better display them to the viewer. Multiple perspectives are conjoined in one image, and it is not clear where the table begins or ends. These still lifes — an important prelude to Cubism — were at once tangible and perplexing.

8 | His home of Aix influenced his work

Cezanne was deeply attached to his native town of Aix-en-Provence. He spent his time between Paris and Aix, and moved back to the South after 1886. There, he painted landscapes firmly grounded in details of local history and geology, like the Bibémus quarry, Château Noir and Mont Sainte-Victoire, together with images of bathers, cardplayers, and other figures.

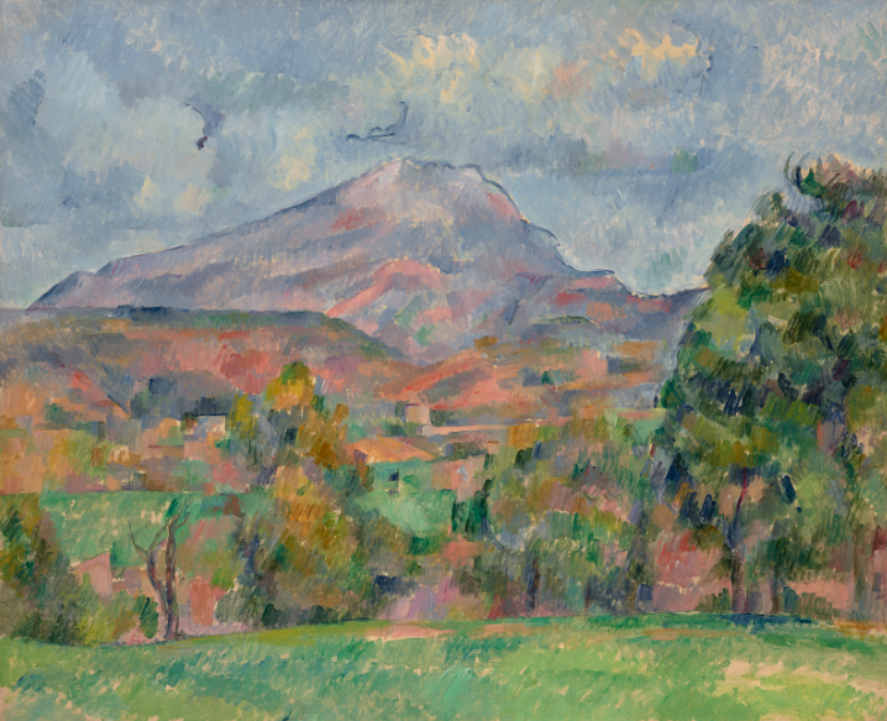

Paul Cezanne (1839-1906), La Montagne Sainte-Victoire, c. 1888-1890. Oil on canvas. 25⅝ × 31⅞ in (65.2 × 81.2 cm).

Sold for $137,790,000. Offered in Visionary: The Paul G. Allen Collection Part I on 9 November 2022 at Christie’s in New York.

Mont Sainte-Victoire was his favourite subject. He produced over 80 paintings of the mountain, and this iconic group of works are especially notable for their proto-Cubist forms. About Cezanne’s views of Sainte-Victoire, Rainer Maria Rilke wrote, ‘Not since Moses has anyone seen a mountain so greatly’.

Cezanne was still painting the countryside around Aix at the time of his death in 1906.

9 | Since his death, Cezanne has received institutional recognition all around the world

A number of important retrospectives following Cezanne’s death were pivotal in bringing his achievements to the public’s attention and inspiring the next waves of the avant-garde. Most seminal of these was at the Salon d’Automne in Paris in 1907. Picasso, Braque and Matisse all crowded in to admire the artist’s works.

Paul Cezanne, The Card Players (Les Joueurs de cartes), 1890–1892. The Barnes Foundation, Philadelphia.

Since then, Cezanne has entered the collections of the most prominent institutions throughout the world. The Museum of Modern Art houses an impressive collection of his still lifes, the Musée D’Orsay’s collection spans the full breadth of his career and the Courtauld Gallery has a world-renowned collection of Cezanne’s landscapes. The Barnes Foundation has the largest holding of Cezanne paintings, numbering 69 works.

10 | Cezanne’s work is highly sought-after in the market today

Some of the highest prices for the artist are commanded by his mature works from the 1880s onwards, such as Si Newhouses’s Bouilloire et fruits (1888-1890), which sold at Christie’s in 2019 for $59,295,000, and L’Estaque aux toits rouges (1883-1885), which sold at Christie’s in 2021 as part of the Cox Collection for $55,320,000.

Paul Cezanne (1839-1906), Paul Cezanne (1839-1906), L’Estaque aux toits rouges, 1883-1885. Oil on canvas. 25¾ × 32 in (65.5 × 81.4 cm). Sold for $55,320,000

at The Cox Collection: The Story of Impressionism, Evening Sale on 11 November 2021 at Christie’s in New York.

Recently, La Montagne Sainte-Victoire (1839-1906) fetched $137,790,000 at Christie’s as part of Visionary: The Paul G. Allen Collection, setting a new record price for the artist.

Source: Christie’s