Peter Paul Rubens’s “Portrait of a Man as Mars” is appearing in Sotheby’s Modern Evening Auction this May, inviting the question: How did the 17th-century Baroque painter become so distinctly modern?

Peter Paul Rubens’s impact on generations of artists, from his 17th-century contemporaries to those working today, can hardly be overstated. His lush and painterly technique, rich colorism, and expansive subject matter have inspired countless artists, who studied his compositions, emulated his style, and aspired to attain his unparalleled reputation as artist-cum-celebrity. As Frank Stella wrote in Working Space, Rubens was an unending “source of pictorial energy.” In Les Fleurs du Mal, Poet Charles Baudelaire described Rubens’s work as existing “where life flows and stirs unceasingly, Like the air in the sky and the water in the sea.” Offered at Sotheby’s Modern Evening Auction on 16 May, Rubens’s Portrait of a Man as Mars, from the prestigious Fisch Davidson Collection, embodies these characteristics.

Sir Peter Paul Rubens. Portrait of a Man as Mars (circa 1620). Estimate: 20,000,000 – 30,000,000 USD.

During his lifetime Rubens left an indelible mark on his pupils, collaborators, and contemporaries. His greatest artistic inventions are exemplified in the work of Anthony van Dyck, universally regarded as his successor and most accomplished pupil. In Amsterdam, Rembrandt, who collected Rubens’s paintings and oil sketches, measured his own success in relation to the Flemish artist and frequently responded directly to Rubens’s pictorial antecedents. Diego Velázquez, upon meeting Rubens in Spain in 1626, engaged in an artistic dialogue with him that prompted the Spaniard to alter his creative process. Rubens’s legacy was passed on by the many students and workshop assistants who trained in his prolific studio. Learning directly from Rubens, they went on to disseminate his creative approach and artistic style.

Rubens’s Enduring Influence

Studio of Sir Peter Paul Rubens. The Assumption of the Virgin, probably mid 1620s. Source: The National Gallery of Art.

“Rubens’ art speaks a universal language,” wrote the prominent scholar Julius S. Held in a 1942 exhibition catalogue. “His creations are [as] polyglot as their author.” A savvy entrepreneur, Rubens oversaw the extensive production of prints made after his greatest paintings and tapestry cycles, thereby ensuring a sphere of influence that transcended geographic boundaries. While the Dutch master himself never traveled to the Americas or Asia, the circulation of such prints enabled artists working far beyond Europe to engage with his work. Jindezhen artisans produced Chinese export porcelain featuring Rubens’s religious and secular compositions. Colonial Latin American artists used engravings after his grand altarpieces as templates for their own works so that reiterations of Rubens’s Assumption of the Virgin (the high altarpiece of Antwerp Cathedral) once filled local churches in Mexico City, Cuzco, and throughout New Spain.

During the 18th century, the greatest exponents of the French Rococo – including Jean-Antoine Watteau, Jean-Honoré Fragonard, and François Boucher – admired Rubens’s expressive freedom and pictorial lyricism. (So adept was Fragonard at copying works by Rubens that some of the Frenchman’s drawings were once incorrectly attributed to him. This was the case with Fragonard’s watercolor sketch after Rubens’s Nessus and Deianeira.) Their fêtes galantes, or parkland scenes in which elegantly dressed figures engage in amorous pastimes, drew heavily on Rubens’s pastoral and mythological paintings, such as Park of Het Steen.

Peter Paul Rubens. The Park of a Castle. Source: Kunsthistorisches Museum.

Antoine Watteau, Embarkation for Cythera. Oil on canvas. Paris, Musée du Louvre, Inv. No. 8525.

In Britain, Sir Joshua Reynolds, the doyen of the Royal Academy, admired “the facility with which [Rubens] invented, the richness of his composition, the luxuriant harmony and brilliancy of his colouring,” that “so dazzle the eye.” A new generation of British collectors acquired important examples of Rubens’s work, enabling subsequent artists to respond directly to him. Thus, after Thomas Gainsborough encountered Rubens’s Watering Place in London in 1768, he painted an homage to the Flemish artist, transporting the Netherlandish landscape to the British countryside. Both are now in The National Galley, London. The impact of Rubens’s landscapes, a genre to which he turned late in life, proved enduring. In a 1833 lecture at Hampstead, John Constable praised “the freshness and dewy light, the joyous and animated character” of Rubens’s atmospheric scenes, which he sought to emulate.

Left: Élisabeth Vigée Le Brun, Self-Portrait in a straw hat. Oil on canvas. London, National Gallery, Inv. No. NG1653. Right: Peter Paul Rubens. Le chapeau de paille. Oil on panel. London, National Gallery, Inv. No. NG852.

The impressive collections of works by Rubens in Europe’s major galleries (those founded as princely collections possessed especially rich holdings) enabled Grand Tourists and artists alike to engage with Rubens. Some, like the French painter Élisabeth Vigée Le Brun undertook special pilgrimages “to see the masterpieces of Rubens.” His Le Chapeau de Paille particularly captivated her. She recounted in her memoirs: “It delighted and inspired me to such a degree that I made a portrait of myself … striving to obtain the same effects … when the portrait was exhibited at the Salon I feel free to confess that it added considerably to my reputation.” Vigée Le Brun’s adaptation of the sitter’s dress partly inspired the “shepherdess” or “peasant” fashion espoused by Marie Antoinette, for whom the artist served as official court painter. An instance of artistic emulation shaping taste, as though from Rubens to the runway.

Peter Paul Rubens. The disembarkation of Marie de’ Medici at Marseilles. Oil on canvas. Paris, Musée du Louvre, Inv. No. MR965.

With the emergence of the Romantic idea of individual artistic genius in the early 19th century, Rubens’s posthumous reputation attained new heights. The German art historian Johann Joachim Winckelmann declared: “Rubens is the glory of art, of his school, of his country, and of all coming centuries; the fertility of his imagination cannot be overrated.” Artists and writers, particularly in France, discovered Rubens anew. With the Musée du Louvre’s extensive collection of his work now free and open to the public, copying Rubens’s paintings became an essential component of artistic training.

In Eugène Delacroix and Théodore Géricault, Rubens found his most ardent admirers. One can hardly imagine Delacroix’s Liberty Leading the People or Géricault’s Raft of the Medusa without Rubens’s Marie de’ Medici cycle (transferred from the Palais du Luxembourg to the Louvre). The indulgent forms, warm colors, and compositional exuberance of these 19th-century masterpieces all pay homage to Rubens, but the ethos is popular revolution, rather than exaltation of the sovereign state.

Edouard Manet, Fishing. Oil on canvas. New York, Metropolitan Museum of Art, Inv. No. 57.10.

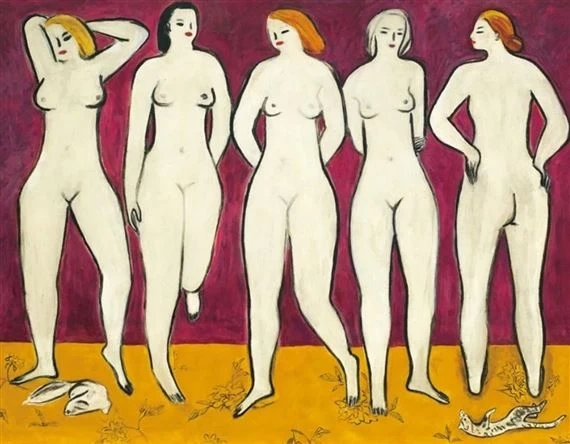

Delacroix, who produced over 100 drawings after works by the “Homer of painting” (as he called Rubens), impressed his importance on the younger generation. He counseled Edouard Manet: “One must look to Rubens, be inspired by Rubens, copy Rubens, Rubens was God.” Manet followed this advice. In Fishing, he evoked Rubens’s Park of Het Steen, even including a self-portrait in the guise of a 17th-century Antwerp patrician, as if to claim the role of artistic heir apparent. Manet’s contemporaries Pierre-Auguste Renoir and Paul Cézanne likewise studied Rubens, transforming his supple, full-figured goddesses into buxom bathers. With Cézanne the voluminous became volumetric.

While artistic trends come and go, Rubens remains a source of artistic inspiration. The multifaceted nature of his art enables artists with remarkably diverse interests to experience its creative stimulus. Echoes of Rubens can be found in Picasso’s Guernica, Lovis Corinth’s Self-Portrait in Armour, and Max Beckmann’s Artists with Vegetables; direct responses in Cindy Sherman’s Untitled #221 (part of her History Portraits series), and Jeff Koons’s Gazing Ball (Rubens Tiger Hunt). As Jenny Saville has said, “Whether you like Rubens or not, his influence runs through the pathways of painting … he changed the game of art.”

Left: Cindy Sherman, Untitled #221. C-Print. Collection of Sue and Bud Selig. Peter Paul Rubens, Portrait of Isabella Brant. Oil on panel. Florence, Galleria Degli Uffizi, Inv. No. 779.

Rubens’s virtuoso application of paint, and the ineffable quality it endows on his paintings, has always entranced spectators. Giovanni Pietro Bellori, writing in the 17th century, wrote of the “fury of his brush,” which appeared “as inspired as a breath of air.” Two centuries later, Vincent van Gogh conveyed the same sentiment when describing the immediacy of Rubens’s brushwork: Rubens paints “with such a swift hand and without any hesitation … how fresh his paintings have remained precisely because of [this].”

Rubens’s brushwork hovers at the intersection of figuration and abstraction. In the words of Jenny Saville, it “describes form in an almost abstract way.” Stella explained, Rubens “advance[d] notions of painterliness, impressionistic color, and continuous pictorial surface, three concerns about painting which more than any others have led inexorably toward twentieth-century abstraction.”

The perhaps surprising importance of Rubens to mid-20th-century Abstract Expressionism is encapsulated in the work of Willem de Kooning, who keenly admired the Baroque painter. As Saville notes, “De Kooning and Rubens are alike because of the nature of their paint–the movement of their mark-making.” Rubens’s “looping of cloth and bodies” becomes de Kooning’s “twisting of the brush and color.” For both, the materiality of the paint pigment and the visible traces of its application reigned supreme.

Peter Paul Rubens, Portrait of Helena Fourment (‘The little fur’). Oil on panel. Vienna, Kunsthistorisches Museum, Inv. No. 688.

For artists like de Kooning, Lucien Freud, Francis Bacon, and John Currin, Rubens also appeals because of his erotic approach to the female form. There is perhaps no franker depiction of postcoital satiation than the rendering of his second wife, Helena Fourment, swathed in fur. One can imagine Rubens agreeing with de Kooning’s dictum, “Flesh was the reason why oil paint was invented.” Indeed, the very word “Rubens” has entered our lexicon, denoting, according to the Oxford English Dictionary, “a voluptuous, full-figured woman.” It appears in literature that runs the gamut from Ernest Hemingway’s A Farewell to Arms to contemporary beach reads; the mobster Johnny Sack even uses the adjective “Rubenesque” in the Sopranos television series.

Rubens’s enduring legacy was the subject of a 2015 exhibition organized by the Royal Academy, London, and the Palais des Beaux-Arts, Brussels. Exploring Rubenism writ large, the show concluded with a final section curated by Saville that examined Rubens’s influence on contemporary artists, herself among them. As Saville explained, “Rubens made artists paint greater works of their own.” Studying Rubens, internalizing Rubens, and understanding Rubens enables contemporary artists to distill their own artistic identities. Salmon Toor and Cecily Brown are among the many young contemporary artists who have expressed admiration for the Baroque master.

A creative lodestar, Rubens remains as relevant today as he was in 17th-century Europe. In 2017 when Louis Vuitton collaborated with Jeff Koons on its “Masters” campaign, images of Rubens’s Tiger Hunt adorned the designer handbags, all emblazoned with his name. Embedded in the cultural psyche, Rubens embodies an idea of enduring mastery that supersedes time and place.

Source: Sotheby’s