Vincent van Gogh’s The Bedroom (1888). Courtesy of the Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam (Vincent van Gogh Foundation).

It was autumn when Van Gogh first slept in the Yellow House and painted what must be the most famous bedroom in art history. The picture is a still life, although one on an enormous scale. What does it tell us about Vincent’s life on the eve of Gauguin’s arrival?

Van Gogh began renting the Yellow House in Arles in May 1888, but it was unfurnished and initially he kept his hotel room and just used the new place as a studio. In August he bought two beds, one for himself and the other for a guest, a fellow artist. He first slept in his own bed there in mid-September. “I can live and breathe, and think and paint”, he wrote with delight to his sister Wil.

It was in this room that Van Gogh composed some of his finest pictures. From Arles he wrote that “the most beautiful paintings are those one dreams of while smoking a pipe in one’s bed”. No doubt this was where he conceived the idea for The Bedroom (1888).

On 16 October Vincent started work on the iconic picture, in order to give his brother Theo an idea of his new home. He advised Theo that “looking at the painting should rest the mind, or rather, the imagination”. For us, today, it gives a glimpse into his domestic life.

Although the bed looks narrow, Van Gogh described it as a “wide double bed” and it has two pillows beside the scarlet blanket. Was he hoping that he might find a woman to share it with? The two chairs prefigure a bold painting of his own “empty chair” which he would make a few weeks later (now at the National Gallery, London).

On the far wall his clothes hang on a row of hooks, along with the straw hat that protected him while working under the strong Provençal sun. On the washstand is a miniature still life—with a water flask and glass, jug and basin, soap, and three bottles (he also presumably kept his razor there). Above this hangs a mirror that he had just bought, presumably used both for grooming and capturing self-portraits.

The perspective almost seems to make the bedroom sway, as in a dream—but this is partly because of the room’s unusual trapezoid shape. The house had a diagonal frontage, where it where it faced a public garden, slicing off the room at an angle near the washstand. The bed seems to loom up at us, with the bedend appearing even higher than the bedhead.

Vincent wrote to Theo that the walls were “pale violet” in the painting. But his pigments have deteriorated: the cochineal red in the blended violet has faded, now leaving the walls a bluish tone. Specialists at the Van Gogh Museum have created a digital recolourised image of what the original painting might have looked like.

Digital recolourised visualisation of the Amsterdam version of The Bedroom. Courtesy of the Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam.

In fact, Van Gogh’s violet walls represented artistic licence. On moving into the house Vincent had written that “it’s painted yellow outside, whitewashed inside”. And he was a notoriously poor housekeeper, so no doubt his clothes would have been scattered all over the floor and on the chairs.

The “paintings within a painting” are intriguing. The two works along the side wall, near the ceiling, are portraits of his artist friend Eugène Boch and the Zouave soldier Paul-Eugène Milliet. Below them, with white mounts, are two works which might be Japanese prints. Above the bedhead is a landscape with a large tree. No such landscape survives, so it could represent a lost Van Gogh, possibly of the hill of Montmajour.

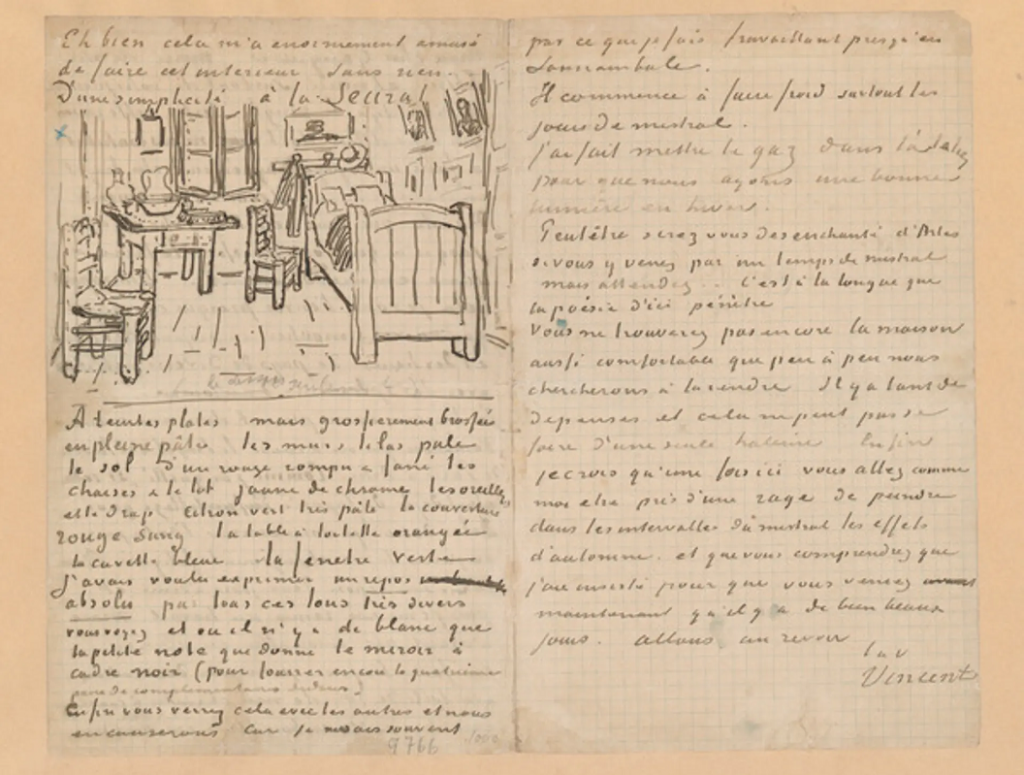

Vincent was delighted with The Bedroom, describing it to Theo as “one of the best” he had done. He also included a small sketch of the painting in a letter to Gauguin, telling his friend that he had set out “to express utter repose”. The letter had been hidden away in private collections until it was bought by collector Eugene Thaw in 2001 and donated six years later to New York’s Morgan Library.

Vincent van Gogh’s letter to Gauguin, 17 October 1888. Courtesy of The Morgan Library & Museum, New York. MA 6447. Photo: Janny Chiu, 2015.

Gauguin arrived in Arles a week after Van Gogh’s letter, for what would end up being a stormy nine-week stay, which ended with the traumatic ear incident. Van Gogh was hospitalised and while he was away Yellow House suffered from damp when the nearby River Rhône flooded. On his return, he was horrified to find that water and saltpetre were oozing from the walls.

Some of his paintings, including The Bedroom, were damaged by moisture and had begun to flake. To dry it out, he applied newspaper onto the surface of The Bedroom, but unfortunately small quantities of the ink then penetrated into the paint.

When conservators examined the picture under magnification a few years ago they found tiny black stains spread across the raised part of the paint surface. Only a few letters could be made out, confirming it was from printed matter, but unfortunately it proved impossible to read the newspaper text. The painting was then conserved, improving its stability and appearance.

Van Gogh later made two copies of the painting, one the same size (now at the Art Institute of Chicago) and a smaller one for his mother and sister Wil (now at the Musée d’Orsay, Paris). The three pictures were brought together for a major exhibition on Van Gogh’s Bedrooms at the Art Institute of Chicago in 2016, a project conceived by the curator Gloria Groom.

The Yellow House was severely damaged by an Allied bomb on 25 June 1944. Although Gauguin’s bedroom survived, Vincent’s adjacent room was mostly destroyed. The ground floor was in slightly better condition and the house could have been rebuilt. Sadly, it was demolished sometime afterwards.

Only a pair of rather fuzzy photographs of the bedroom seem to survive, taken in 1933. The window panes are as in Van Gogh’s day, with the washstand replaced by an armchair.

A few years ago I tracked down what happened to Van Gogh’s actual bed. In June 1890 he had the bed “flat-packed” in Arles and sent to him in Auvers-sur-Oise, the village north of Paris where he was working. After Van Gogh’s suicide, the following month, Theo inherited the bed. Astonishingly, the bed remained with Theo’s son right up until the end of the Second World War, when it was in their house in Laren, outside Amsterdam.

Theo’s grandson, Johan van Gogh (then 93), told me the story. Astonishingly, he recalled that in 1945 his father had donated the bed to victims of wartime bombing who were living “somewhere in the Arnhem area”, in the eastern Netherlands. I then contacted a local historian in Laren who told me that the villagers had collected several truckloads of furniture to donate to Boxmeer, a small town 40km south of Arnhem. Photographs of the lorries arriving in Boxmeer survive.

The story of the Boxmeer bed was extensively covered in the Dutch media in 2016, and there was always a remote hope that Van Gogh’s bed might turn up in someone’s attic. Sadly, the bed has not been found. But the town’s major hotel, the Riche, has recreated the scene depicted in The Bedroom so that guests can dream they have been transported back to the artist’s time.

“Van Gogh Bedroom”, Hotel Riche, Boxmeer. Courtesy of Hôtel Riche, Boxmeer.

Written by Martin Bailey

Source: The Art Newspaper