Does mental illness exempt painters from exercising their profession? Or can the affliction actually improve the artists creation? Van Gogh answered both questions in the last years of his life.

“…my health is good, and as for my brain, that will be, let us hope, a matter of time and patience.”

Vincent van Gogh wrote the above sentence in a letter to his brother Theo, dated June 1889. He had been a resident of the Saint-Paul-de-Mausole asylum in Saint-Rémy, southern France, for around a month. Plagued by anxiety, depression, agoraphobia, and auditory hallucinations, he would spend a year in the asylum’s care. Like much of Van Gogh’s life, it would be a period of great productivity and great anguish.

Hospital at Saint-Rémy, 1889, oil on canvas, Hammer Museum, Los Angeles

Even though the Dutch-born painter suffered from mental afflictions most of his life, it wasn’t until his later years that the emotional turmoil he frequently experienced became exceedingly severe, resulting in seven distinct crises over the course of around two-and-a-half years. It is interesting to note that in these years Van Gogh’s style would grow even more distinctive, his brushstrokes often coiling into a seething mass of vivid color and shape, forming pieces both profoundly beautiful and deeply visceral. Could it be that Van Gogh’s painting improved as his mental condition worsened? Or was it simply the natural evolution of style?

During these dwindling years, Van Gogh ostensibly hinted in his paintings at the foreseen shortness of his life. The symbolism, themes, technique, and color more than amply portray a poignant sense of mortality.

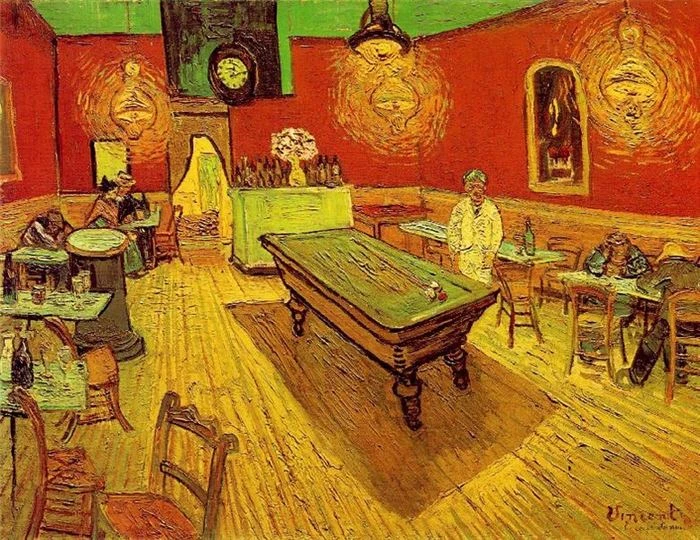

The Night Café, 1888, oil on canvas, Yale University Art Gallery, New Haven

“In my picture of The Night Café, I have tried to express the idea that the cafe is a place where one can ruin oneself, go mad or commit a crime…and all this in an atmosphere like a devil’s furnace of pale sulphur.”

There certainly is a hellish intensity to The Night Café. The lone patron dressed in white beneath the searing, otherworldly lights, the figures slumped at small tables as if in the throes of a despair too deep to climb out of, while a gentleman in a straw hat leers with lupine intent at the woman seated to his right. In short, it is a small tableau of infernal insanity.

After his unfortunate and infamous experience in Arles, Van Gogh voluntarily checked himself into Saint-Rémy. Director Peyron interviewed him on admission, and entered the following notes into the asylum register:

“…suffering from acute mania with hallucinations of sight and hearing which have caused him to mutilate himself by cutting off his ear. At present he seems to have recovered his reason, but he does not feel that he possesses the strength and the courage to live independently…my opinion is that M. van Gogh is subject to epileptic fits at very infrequent intervals.”

While no official diagnosis was ever made regarding Van Gogh’s condition, Dutch psychiatrist Dr. G. Kraus (whose opinion is appended to the U.S. edition of Van Gogh’s letters) made an eloquent insight when refusing to label the artist’s affliction:

“He was an individual in his illness, as well as in his art.”

During his stay in Saint-Rémy, Van Gogh would possess long periods of lucidity, punctuated by a further three violent attacks, lasting two to three months at a time. He was 36 years old when he checked himself in. He would be dead at 37.

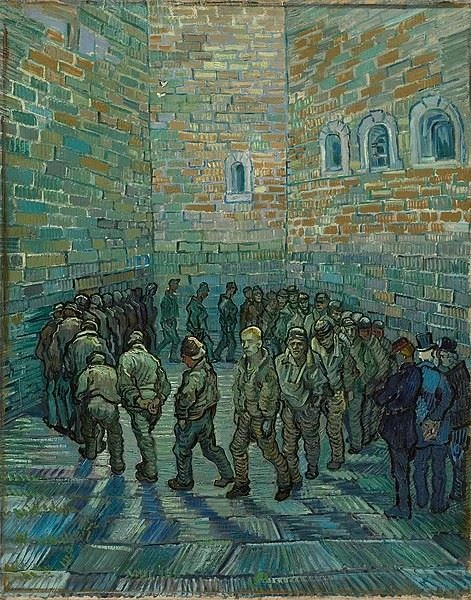

Prisoners’ Round (after Gustave Doré), oil on canvas, 1889,

The Pushkin State Museum of Fine Arts, Moscow

Van Gogh copied Prisoners’ Round by Gustave Doré, an artist he very much admired, from a print of Newgate Prison, London.

“My surroundings here begin to weigh on me…I can’t go on, I am at the end of my patience.”

This piece perfectly encapsulates the mental anguish that was afflicting Van Gogh during his stay at Saint-Rémy. The looming brick walls, the visiting officials engaged in idle chit-chat as the prisoners traipse in a perpetual circle, descending into some further level of personal hell, and Vincent looks out at the viewer with a look of such pitiful sorrow, such utter desolation, that even the most stoic creature cannot help but feel at least some semblance of despair.

“Well, with this mental disease I have, I think of the many other artists suffering mentally and I tell myself that this does not prevent one from exercising the painter’s profession as if nothing was amiss.”

This timeless insight by Van Gogh was taken from another letter to his beloved brother Theo and opens up great opportunity for discussion and debate. Is some level of despair – or at least dissatisfaction – necessary to create truly great art? And if that is the case, does that make one’s mental affliction a blessing? Van Gogh’s mental state was in decline during his time in Saint-Rémy, and his last years were some of his hardest, but during his stay in the asylum he produced over 140 paintings. It isn’t difficult to draw the parallels.

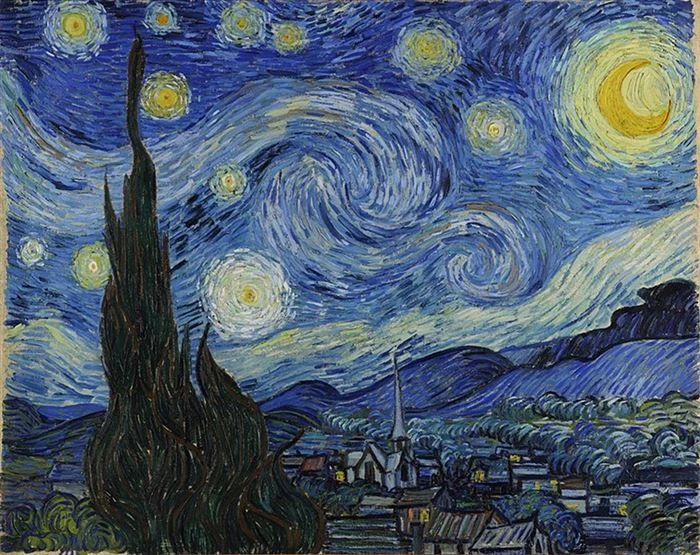

The Starry Night, 1889, oil on canvas, The Museum of Modern Art, New York City

Van Gogh’s masterpiece The Starry Night is a painting of absolute beauty, but it also seems to hint at the utter chaos that swarmed in the artist’s mind. The swirls of the night sky, the flamelike tendrils of the cypress tree, the ocean-esque roll of the surrounding hills. These are all very indicative of a mind in the throes of a psychological episode.

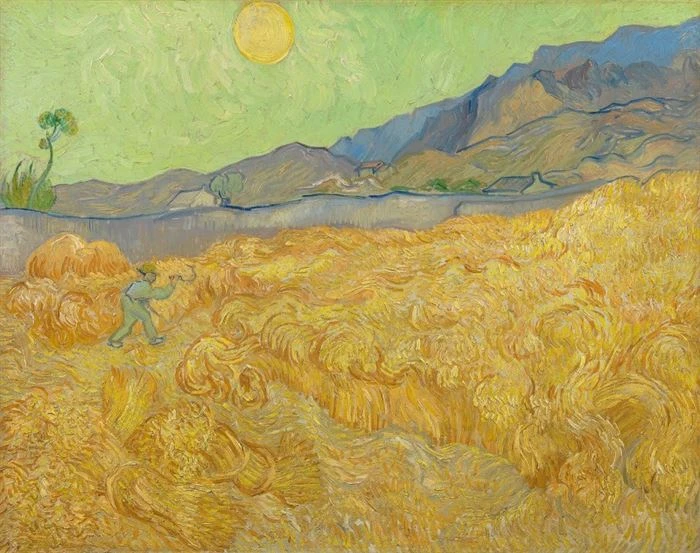

Speculation and assumption can easily be applied on an artist’s work. This is no profound act. But Van Gogh himself explained some of the darker symbology behind his painting Wheatfield with a Reaper in a letter to his brother:

“…I see in him the image of death…But there’s nothing sad in this death, it goes its way in broad daylight with a sun flooding everything with a light of gold.”

Could these be the writings of a man who knew he was close to the end?

Wheatfield with a Reaper, 1889, oil on canvas,

Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam (Vincent van Gogh Foundation)

On May 16, 1890, Van Gogh left the asylum at Saint-Rémy for Paris. He stayed with Theo for three days, before retiring to Auvers. On July 27, he walked out into a nearby wheat field and shot himself in the chest. He died in Theo’s arms two days later.

Van Gogh suffered a life of mental anguish, and, for the most part, artistic obscurity (he only ever sold one painting). It is deeply saddening that he never lived to see his artwork gain the respect and appreciation that it deserved. In his last letter to Theo, dated July 23, 1890, and found upon his person after suffering the self-inflicted gunshot wound, Van Gogh wrote:

“Well, the truth is, we can only make our pictures speak.”

And he did that more than adequately.

Written by Benjamin Blake Evemy

Source: Mutual Art