The Spanish artist Francisco José de Goya y Lucientes—destined to be known simply as Goya—painted what he saw, and what he saw wasn’t pretty. Over the course of his long life, soldiers fired at children while incompetent politicians brought Spain to the brink of ruin. This may explain why his work continues to shock almost two centuries after his death: It can be hard to fight the feeling that nothing has really changed between then and now. To quote the critic Robert Hughes, author of a 2003 biography of the artist: “He speaks to us with an urgency that no artist of our time can muster. We see his long-dead face pressed against the glass of our terrible century, Goya looking in at a time worse than his.”

Goya may have been a pessimist, but he knew how to make pessimism enthralling. His prints and paintings can be side-splittingly funny, and they’re strikingly beautiful, even (or especially) when they depict ugliness. Throughout his career, he remained clear-eyed enough to see the world as it really was—and brave enough to find the dark humor therein.

Parasol (1777)

Francisco de Goya, The Parasol, 1777. Museo del Prado, Madrid. Photo via Wikimedia Commons.

It’s one of art history’s greatest ironies that Goya, usually considered the preeminent Spanish painter of the late 18th century, failed to earn admission to a single art school. Perhaps for the best, his path to success was long and uneven, giving him ample time to cultivate an unmistakable style. Goya spent much of his twenties in Rome and Madrid studying the works of Raphael, Diego Velázquez, and other Old Masters, and by 1773, the year he married, he’d won major commissions from the Spanish nobility.

With its cheery colors and tranquil composition, Parasol, completed the same year Goya turned 31, may not seem to bear much of a resemblance to the dark masterpieces that followed. Instead, it suggests the ongoing influence of the Old Masters, whose works Goya had encountered in Italy. Even if Goya was still grasping for a mature style, however, the painting shows off his talents, especially his keen eye for facial features. In the coming decades, he’d perfect the art of distorting and exaggerating the human face, often to stunning comedic effect.

Manuel Osorio Manrique de Zúñiga (1787–88)

Francisco de Goya. Manuel Osorio Manrique de Zuñiga (1784–1792), 1787–1788. The Metropolitan Museum of Art

Historians love to argue about when the modern era began. Here’s a dark-horse theory: Modernity kicked off in 1788 in the form of three cats lurking in the lower left quadrant of Goya’s Manuel Osorio Manrique de Zúñiga, often called Red Boy.

In the late 1780s, when Goya was the preferred portraitist in the court of King Charles III, the powerful Count of Altamira commissioned him to paint his youngest child, Manuel. Goya chose to depict the little boy in an adorable red suit, playing with a pet magpie. Look closer, however, and the sentimentality of the scene quickly sours. From the shadows, the trio of cats stares hungrily at the helpless bird, ready to pounce.

Modern life, as Goya saw it, was a sick joke, equal parts scary and absurd—a bird always on the verge of being gobbled up. His work is adept at conveying a disturbingly contemporary-seeming point of view, exposing the horrors hidden in plain sight.

Naked Maja (1797–1800)

Francisco de Goya. The Nude Maja, ca. 1800. Museo del Prado, Madrid.

Goya’s status as court painter gave him the chance to curry favor with some of Spain’s most powerful men and women, including the Duchess of Alba, with whom he is thought to have had a lengthy affair. She’s sometimes presumed to be the model for the jaw-dropping nude figure in Naked Maja, likely commissioned by the future prime minister, Manuel de Godoy.

In an age of endless Kim Kardashian selfies, it’s hard to imagine the stir this image caused at the time. As depicted in Spanish art, nude female bodies tended to belong either to idealized Greek goddesses or, on the other end of the spectrum, “wicked” prostitutes. Goya mixed the sacred with the profane by painting this contemporary woman, including her pubic hair—uncontroversial by today’s standards, but almost unheard of in European art at the time—in the elegant, reclining pose of a Titian Venus. With the rise of the Spanish Inquisition a decade later, Naked Maja earned Goya the hostility of the Catholic clergy. He managed to protect his artwork’s reputation, and his own, by citing the hundreds of Old Masters who’d painted the reclining female figure before him. Not for the last time, Goya used artistic respectability as a Trojan horse for his impish ends.

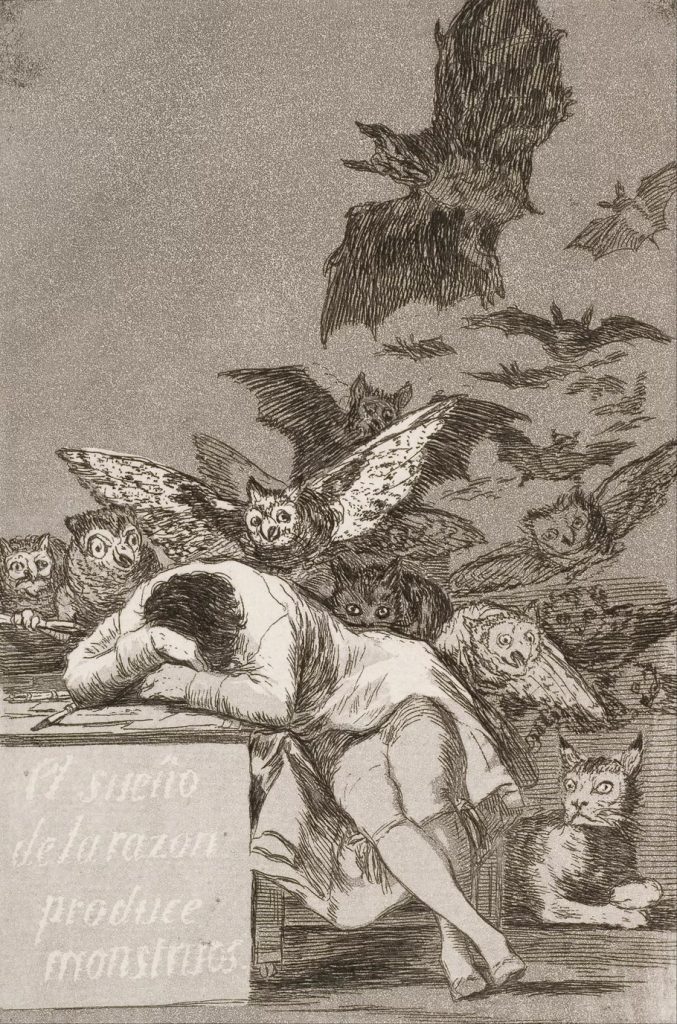

The Sleep of Reason Produces Monsters (1797–98)

Francisco de Goya. The Sleep of Reason Produces Monsters, No. 43 from Los Caprichos (The Caprices), 1796-1798. Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, Kansas City, Missouri.

By 1793, Goya had all but lost his sense of hearing. Scholars still debate the reason why: It’s possible he contracted polio, though some have blamed syphilis or even the lead in his paints. What’s clear is that, after 1793, Goya’s art became more incisive and often more dangerous.

The Sleep of Reason Produces Monsters is the most famous of “Los Caprichos,” a series of 80 etchings Goya created in the late 1790s. It’s also something of a mission statement for the artist’s satirical middle period. Among these etchings, it’s not unusual to find a dotty crone admiring herself in the mirror, a donkey smugly celebrating its family tree, or a gaggle of wizened noblemen crushing the proletariat under their weight. Throughout the series, Goya’s real targets are Spain’s power elites and, even more basically, the absence of reason that permitted their tyranny. Goya later withdrew his prints from circulation, recognizing that he’d already made too many enemies. Better to mock the monsters behind their backs.

The Third of May 1808 (1814)

Francisco de Goya. The Third of May, 1814. Museo Nacional del Prado, Madrid.

In November 1807, French troops invaded Spain and installed a new ruler. For the next six years, Spanish rebels fought the occupation; their resistance was the first ever to be termed “guerilla warfare.” In the early hours of May 3, 1808, French soldiers carried out orders to round up and execute hundreds of suspected rebels.

Goya may have been present for the massacres. Then again, he may have been working from eyewitnesses’ descriptions. In either case, The Third of May 1808 represents the culmination of his artistic development over the previous three decades. The subtle lighting signals his careful study of the Old Masters, though the scene he’s chosen to illuminate is grislier than anything Velázquez ever dreamed up. The bloody corpses signal his indifference to good taste. But above all, the painting signals Goya’s cold, quiet fury with his own society. He doesn’t simply accuse the French soldiers of war crimes—in fact, there’s almost nothing in the frame to indicate the figures’ nationality. Instead, his nightmare transcends time and place: The faceless troops might as well be Nazis at Dachau or GIs at My Lai. It’s this grim universality that makes The Third of May 1808, in the words of Robert Hughes, “truly modern…the picture against which all future paintings of tragic violence would have to measure themselves.”

Saturn Devouring His Son (1819–23)

Francisco de Goya. Saturn Devouring One of His Sons. (From the series of Black Paintings.), 1819-1823. Museo Nacional del Prado.

In his seventies, widowed, and out of favor with the monarchy, Goya relocated to Bordeaux, France. It was here that he completed his final great series: the 14 “Black Paintings.” Unlike the bulk of his earlier works, these were never meant for public viewing. Examining the massive Saturn Devouring His Son (1819–23), it’s not hard to see why. Goya chose as his subject one of the bleakest episodes from Greek mythology, in which the god of time ensures his survival by eating his offspring. Often interpreted as an allegory for the decay of the Spanish state, Saturn twists expectations by showing time as a babyish brute, as pathetic as he is terrifying.

Across Goya’s hundreds of prints and paintings, the same type of face keeps reappearing: goggle-eyed, mindless, and uncontrollably greedy. Sometimes this face belongs to an animal, sometimes it belongs to a human being, and sometimes, it’s hard to tell. It skulks in the background of Red Boy, emerges from the shadows in The Sleep of Reason—and in Saturn, completed just a few years before Goya’s death, it finally shows itself without shame.

Might this face symbolize the nightmare of modernity as Goya experienced it? Over the course of his 82 years, the Spanish state collapsed and Europe waged a brutal war with itself—enough greed and stupidity for 10 lifetimes. In response, Goya offered a deceptively simple artistic motto: “Yo lo vi” (“I saw it”). Those three words communicate an idea as necessary in the 21st century as it was in the 19th: In dark times, bearing witness to the truth is not for the faint of heart.

Source: Artsy