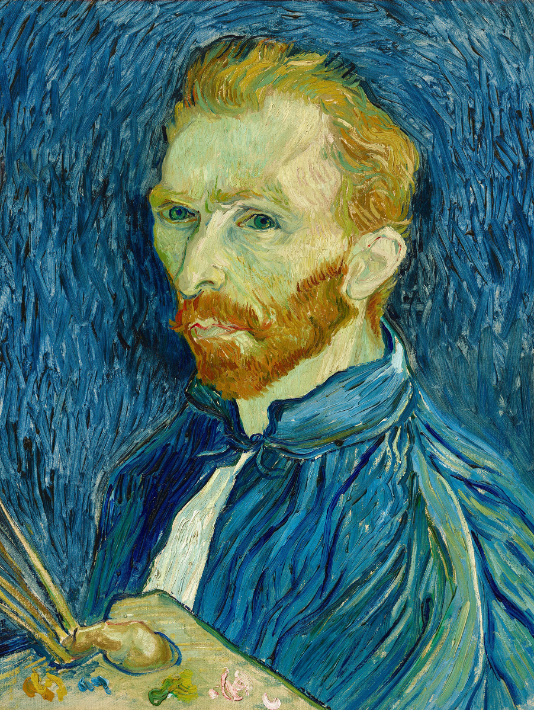

The first ever Van Gogh exhibition at the National Gallery in London suggests that he was not so much a tortured genius as an artist who planned his work meticulously and thought deeply about its execution and meaning. The show’s co-curator, Cornelia Homburg, explains why

Featuring more than 60 works, Van Gogh: Poets and Lovers, a new exhibition at London’s National Gallery, focuses on the years that Vincent van Gogh spent in the south of France — in Arles and Saint-Rémy-de-Provence — between February 1888 and May 1890. The period resulted in pictures of remarkable originality and expressiveness, such as the ‘Sunflowers’ series and two ‘Starry Night’ paintings, which are among the best-known works in all of modern art.

Supported by Christie’s, the exhibition is the first ever at the National Gallery devoted to Van Gogh, and is being held as part of the celebrations marking that institution’s bicentenary in 2024. We spoke to its co-curator, Cornelia Homburg, to find out more.

The show begins as Van Gogh leaves Paris behind for the town of Arles in Provence, aged 34. What changed as he left one place for the other?

Cornelia Homburg: Well, apart from obvious things such as the light and the landscape, there’s also the fact that in Paris he was still, to some degree, experimenting and finding himself artistically. In the south of France, he was more knowledgeable about how to create pictures. There was both a growing mastery in his work and a growing deliberation over what went into it.

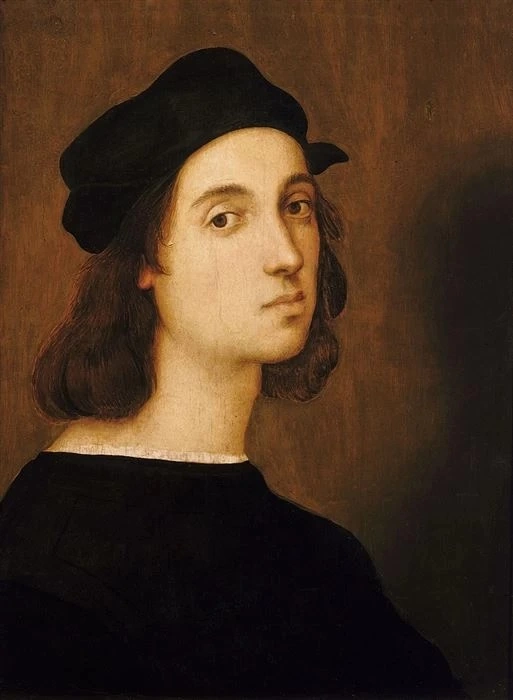

Vincent van Gogh (1853-1890), Self-Portrait, 1889. Oil on canvas. 57.9 x 44.5 cm.

National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C. Collection of Mr and Mrs John Hay Whitney.

Photo: Courtesy National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C.

Your use of the word ‘deliberation’ is interesting. Most people associate Van Gogh with an impetuous, instinctive approach to art-making. Are they wrong?

CH: People love Van Gogh because they feel the passion in his work and believe he poured his emotions right into it. To a certain extent, that’s true. However, he also thought carefully about how to create meaning in his pictures, so as to affect the viewer.

In a letter from July 1888 to [his brother] Theo, for example, he complains that it is hard to stand in a field, keep various colours in mind, and decide how and where to apply them, so that they work best pictorially. ‘You have to think of a thousand things at the same time,’ he wrote. This is not an artist crazily brushing his paint about the canvas without considering what he’s trying to achieve.

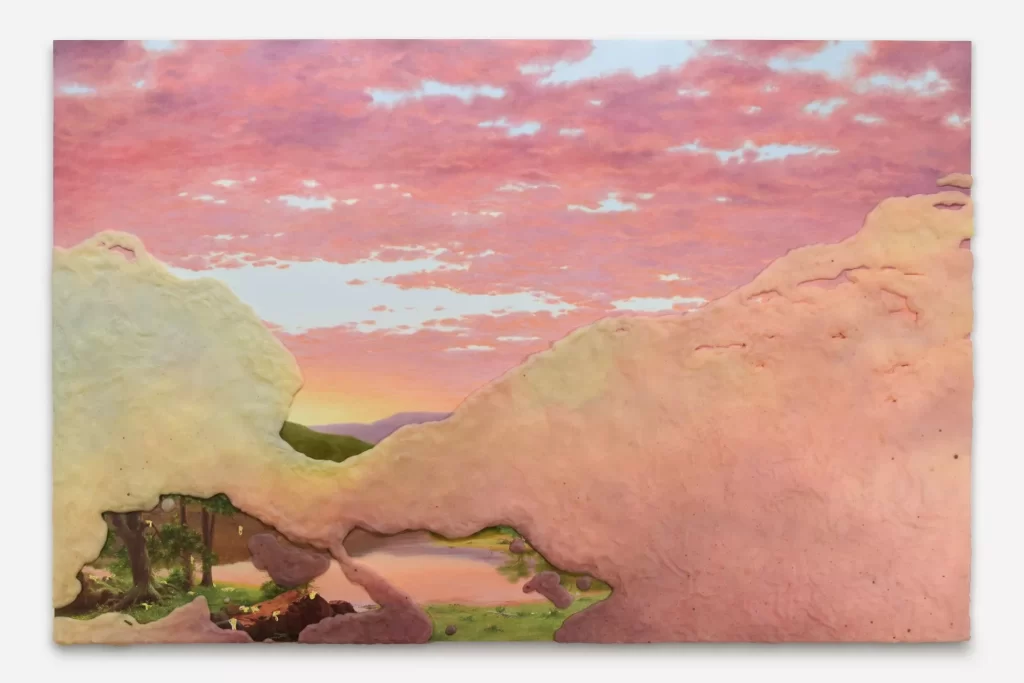

Vincent van Gogh (1853-1890), Landscape at Saint-Rémy (Enclosed Field with Peasant), 1889. Oil on canvas. 76.2 x 95.3 cm.

Indianapolis Museum of Art at Newfields

In contrast to the standard view of Van Gogh as an isolated genius, when he was in the south of France he kept up to date — through letters — with what was happening in Paris [where he had artist friends and where Theo was an art dealer]. After moving to Arles, he thought: I have to craft my own identity now, I have to be clear about what I’m doing and contribute a new direction for art. He talked specifically about creating the ‘art of the future’.

Can you give an example of this new direction?

CH: Yes, colour. He decided that this was going to be one of his foremost modes of expression. The Provençal landscape, with its intense light and beautiful weather, was well suited for this purpose. He came to the conclusion that colour, in heightened form, would be a key element to express the intensity, imagination and emotion he wished to convey in his art.

Another part of his new direction was the frequent inspiration he took from poetry to create idealised or invented settings, transforming motifs or models to achieve fresh meaning.

Vincent van Gogh (1853-1890), Starry Night over the Rhône, 1888. Oil on canvas. 73 x 92 cm.

Musée d’Orsay, Paris. Photo: © Musée d’Orsay, Dist. RMN-Grand Palais / Patrice Schmidt

I assume this connects to the title of the exhibition, Van Gogh: Poets and Lovers. Please tell us more.

CH: In the south of France, ideas associated with poetry and love evolved into central themes for Van Gogh. In paintings such as The Poet’s Garden, for example, he imagined a small public park in Arles as a garden where Italian Renaissance poets such as Petrarch and Boccaccio strolled. Similarly, pairs of lovers appeared in many of his works from this time, such as Starry Night over the Rhône.

Poetry and love are perhaps little-known themes in Van Gogh’s oeuvre, but they were definitely important ones. In the case of the former, he was a voracious reader; and in the case of the latter, there might have been a personal interest, given the fact that he tried and consistently failed to have a serious romantic relationship.

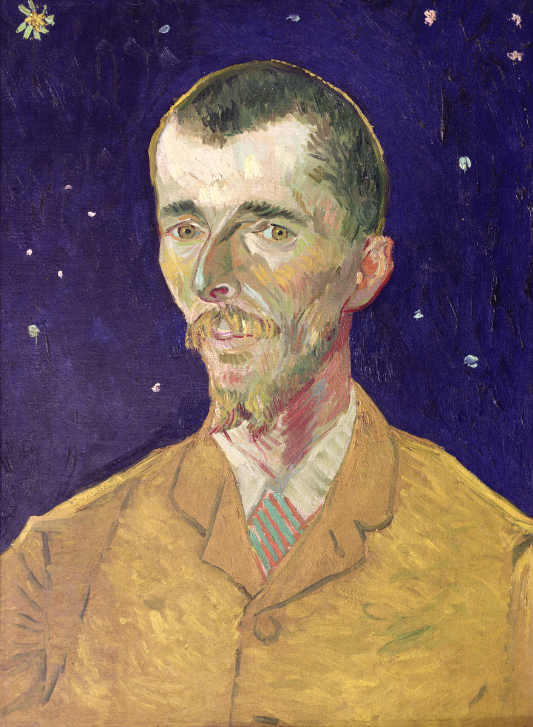

Vincent van Gogh (1853-1890), The Poet (Portrait of Eugène Boch), 1888. Oil on canvas. 60.3 x 45.4 cm.

Musée d’Orsay, Paris. Photo: Bridgeman Images

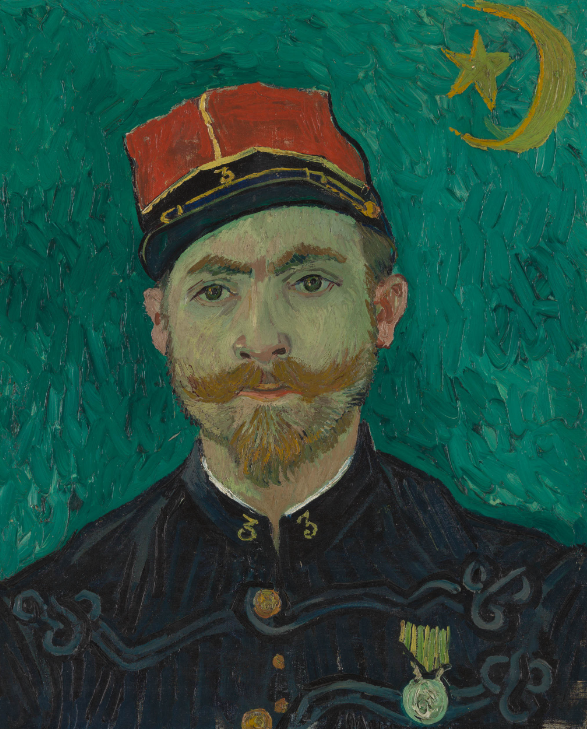

Vincent van Gogh (1853-1890), The Lover (Portrait of Lieutenant Milliet), 1888. Oil on canvas. 60.3 x 49.5 cm.

Collection Kröller-Müller Museum, Otterlo, the Netherlands

Bigger than that, though, these were two themes that allowed him to convert reality into a place of ideals, myths and symbolic overtones. The exhibition will open with one work called The Poet and another called The Lover. Though they depict the two young men in Arles who sat for him, they are not portraits. These men assumed respective roles, as examples of what Van Gogh thought the perfect lover and the perfect poet might look like: one embodying transcendence, the other insouciant sensuality.

Beyond the themes of poetry and love, the exhibition includes a number of famous works from the artist’s time in Provence. What are the standouts?

CH: There are so many — from public and private collections alike. One highlight is the hanging of the National Gallery’s own Sunflowers painting near another from the Philadelphia Museum of Art, which is being lent for the first time in its history. [Van Gogh produced seven ‘Sunflowers’ paintings in total while in Arles.]

Vincent van Gogh (1853-1890), Sunflowers, 1888. Oil on canvas. 92.1 x 73 cm.

The National Gallery, London

In a letter to Theo from May 1889, the artist sketched out a plan for two ‘Sunflowers’ pictures to be displayed as a triptych, along with one of his five paintings [of the local postmaster’s wife] known as ‘La Berceuse’. Van Gogh never realised his plan, but we have now done so, with the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston lending us La Berceuse (The Lullaby).

Vincent van Gogh (1853-1890), La Berceuse (The Lullaby), 1889. Oil on canvas. 92.7 x 72.7 cm.

Bequest of John T. Spaulding. Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

Van Gogh thought a great deal about how he wanted his artworks to be shown. It never came to anything in the end, but another example was in the autumn of 1888 when he discussed the prospect of exhibiting a set of his pictures alongside those by Seurat, Signac and Gauguin. This was to be at an avant-garde event held the following year, to coincide with the Exposition Universelle in Paris.

Van Gogh returned to the north of France in May 1890 and died two months later. Why did you decide to exclude that period from your focus?

CH: In short, because his time in Auvers-sur-Oise [the village near Paris where he spent the last part of his life] is a different chapter in his story — a chapter that was covered in a superb recent exhibition, which was seen at the Van Gogh Museum in Amsterdam and subsequently the Musée d’Orsay in Paris.

Our focus is on the time he lived in Arles and then in nearby Saint-Rémy [where he spent several months in a mental-health hospital and continued to work prodigiously]. This whole period lasted little more than a couple of years, and is popularly associated with the incident on 23 December 1888 [when Van Gogh severed part of his left ear after a row with Gauguin]. However, as we hope the exhibition proves, it was also a period in which he came to maturity as a modern artist.

Supported by Christie’s, Van Gogh: Poets and Lovers is at the National Gallery in London from 14 September 2024 to 19 January 2025

Source: Christie’s