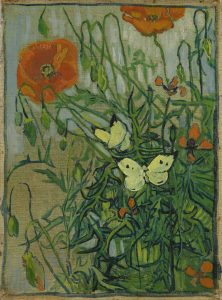

Japanese printmaking was one of Vincent’s main sources of inspiration and he became an enthusiastic collector. The prints acted as a catalyst: they taught him a new way of looking at the world.

But did his own work really change as a result?

“And we wouldn’t be able to study Japanese art, it seems to me, without becoming much happier and more cheerful, and it makes us return to nature, despite our education and our work in a world of convention.” — Vincent to his brother Theo, 23 or 24 September 1888

1, Discovering Oriental art

There was huge admiration for all things Japanese in the second half of the nineteenth century. Vincent did not pay much attention to this japonisme at first.

Very few artists in the Netherlands studied Japanese art. In Paris, by contrast, it was all the rage. So it was there that Vincent discovered the impact Oriental art was having on the West, when he decided to modernise his own art.

Vincent bought his first stack of Japanese woodcuts in Antwerp and pinned them to the wall of his room. He described the city to his brother with these exotic images in mind.

“My studio’s quite tolerable, mainly because I’ve pinned a set of Japanese prints on the walls that I find very diverting. You know, those little female figures in gardens or on the shore, horsemen, flowers, gnarled thorn branches.” — Vincent to his brother Theo from Antwerp, 28 November 1885

2, Japan in Paris

Vincent moved into his brother’s Paris flat in early 1886. Together, they built up a sizeable collection of Japanese prints. Vincent soon began to view them as more than a pleasant curiosity. He saw the prints as an artistic example and thought they were equal to the great masterpieces of Western art history.

We don’t know exactly how big Vincent’s collection was at the time. He refers to ‘hundreds’ of prints in his letters.

“Japanese art is something like the primitives, like the Greeks, like our old Dutchmen, Rembrandt, Potter, Hals, Vermeer, Ostade, Ruisdael. It doesn’t end.” — To Theo from Arles, 15 July 1888

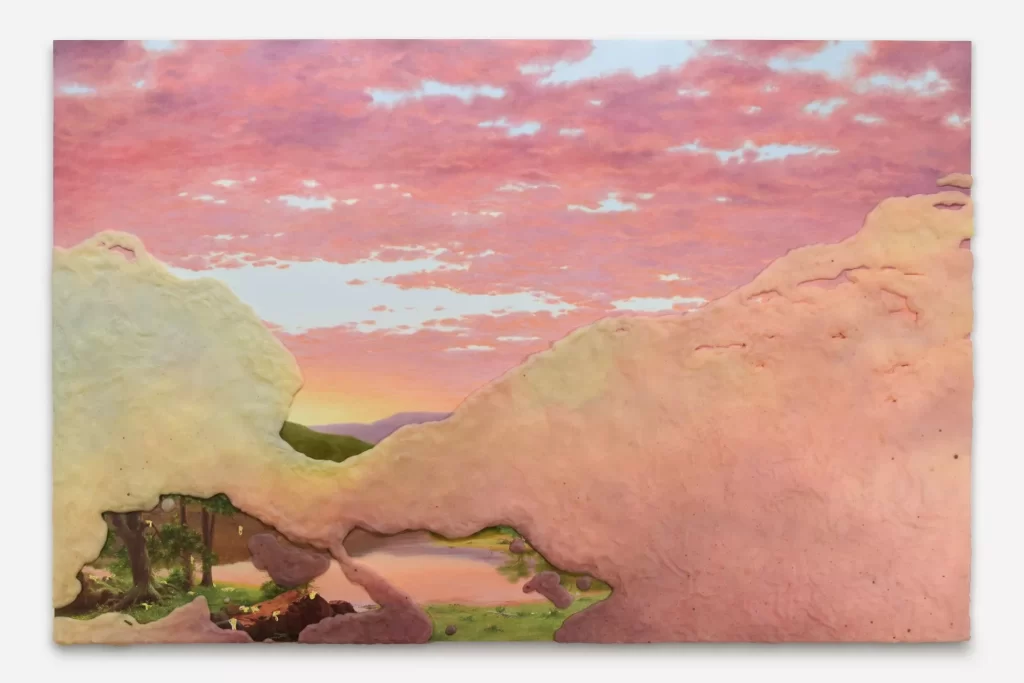

3, Spatial effect and colour

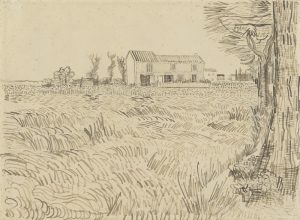

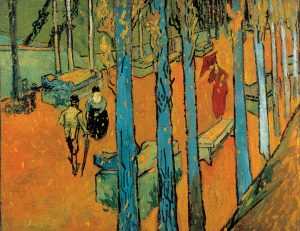

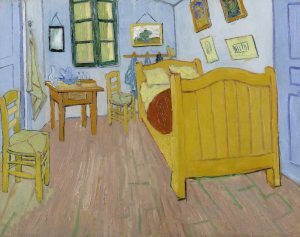

Japanese artists often left the middle ground of their compositions empty, while objects in the foreground were sometimes enlarged. They regularly excluded the horizon too, or abruptly cropped the elements of the picture at the edge.

Western artists learned from all this that they did not always have to arrange their artworks in the traditional way, from close up to far away as if in a peep show.

Vincent adopted these Japanese visual inventions in his own work. He liked the unusual spatial effects, the expanses of strong colour, the everyday objects and the attention to details from nature. And, of course, the exotic and joyful atmosphere.

4, New style

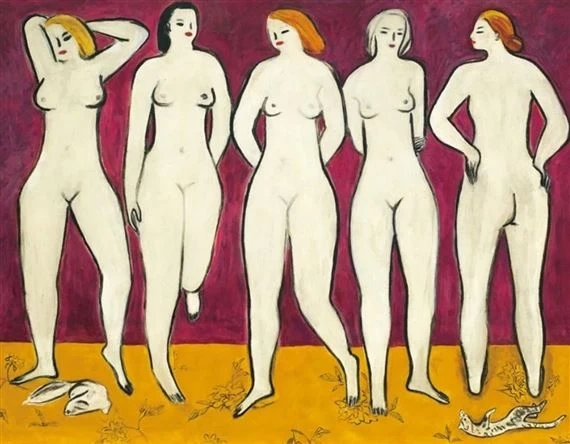

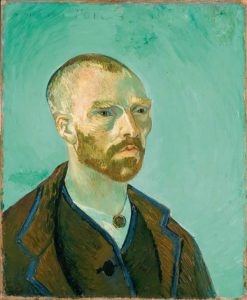

Vincent did more than simply copy Japanese prints. He was influenced in part by his artist friend Émile Bernard, who developed new ideas about the direction of modern art. Taking Japanese prints as his example, Bernard stylised his own paintings. He used large areas of simple colours and bold outlines.

Inspired by Bernard, Vincent began to suppress the illusion of depth in favour of a flat surface. He combined this pursuit of flatness, however, with his characteristic swirling brushwork.

“Look, we love Japanese painting, we’ve experienced its influence — all the Impressionists have that in common — and we wouldn’t go to Japan, in other words, to what is the equivalent of Japan, the south [of France]? So I believe that the future of the new art still lies in the south after all.” — Vincent to his brother Theo from Arles, on or around 5 June 1888

5, Japan in the South of France

After two years, Vincent left the bustle of Paris behind. He set off for Arles in the South of France in February 1888. In addition to peace, he hoped to find the ‘clearness of the atmosphere and the gay colour effects’ of Oriental prints.

He wrote to his friend Gauguin, who was also very taken with Japanese examples, that he had looked through the train window to see ‘if it was like Japan yet! Childish, isn’t it?’

Vincent, like Gauguin, believed that artists should move to more southern, primitive regions, in search of vibrant colours. This would help them take art to a new stage. It was with that idea in mind that he moved to Arles.

“After some time your vision changes, you see with a more Japanese eye, you feel colour differently. I’m also convinced that it’s precisely through a long stay here that I’ll bring out my personality.” — Vincent to his brother Theo from Arles, 5 June 1888

6, Shattered ideals

Vincent hoped to found an artists’ community in Arles along the lines of Japanese Buddhist monks, who lived in similar groups.

In the end, only Gauguin came. He painted from the imagination and encouraged Vincent to work in a more stylised way too. A painting wasn’t supposed to be a photograph.

Sadly, Vincent and Gauguin disagreed too often and Gauguin returned to Paris after a few months. Vincent was beginning to show the first signs of mental illness. He was admitted to hospital and later to a psychological clinic, and he lost faith in his own ability.

Helping develop the art of the future was too ambitious a goal. Vincent referred less and less frequently in his letters to Japanese printmaking.

7, Innovation after the Japanese model

Nature was the point of departure for Vincent’s art throughout his life. It was the same for Japanese artists, and he recognised that. At the same time, Japanese prints gave him the example he needed to modernise.

Vincent was keen to respond to the call for a modern, more primitive kind of painting. Japanese prints, with their expanses of colour and their stylisation, showed him the way, without requiring him to give up nature as his starting point. It was ideal.

“All my work is based to some extent on Japanese art…” — Vincent to his brother Theo from Arles, 15 July 1888

Source: Van Gogh Museum