Wassilly Kandinsky photographed in 1936. Photo: Boris Lipnitzki/Roger-Viollet/Topfoto

The Moscow-born artist is widely acknowledged as one of the fathers of abstraction. Here, Alastair Smart picks out key moments and works from an extraordinary life — illustrated with outstanding works offered at Christie’s

An encounter with Monet changes everything

Wassily Kandinsky was born in Moscow in 1866 to a multicultural, bourgeois family: his father was a tea merchant from Siberia, his mother descended from Mongolian aristocracy. He trained as a lawyer, and was Associate Professor of Law at Moscow University before ever picking up a paintbrush. Everything changed when, in 1896, he came upon a painting from Monet’s ‘Haystack’ series in an exhibition — and was awestruck. The way the worldly forms dissolved into a blaze of colour ‘surpassed [his] wildest dreams’, Kandinsky would later explain.

A move to the Alps sparks a stunning advance

That year, at the age of 30, Kandinsky abandoned his career and moved to Munich to study art. Among the early styles he embraced were Impressionism and Jugendstil (the German equivalent of Art Nouveau). Travels across the rest of Europe followed, before he settled with his lover, Gabriele Münter, in the picturesque Bavarian town of Murnau in the foothills of the Alps.

Wassily Kandinsky (1866-1944) ‘Murnau — Ansicht mit Burg, Kirche und Eisenbahn’ 1909. 18⅞ × 27⅛ in (48 × 69 cm). Sold for £6,761,250 on 6 February 2013 at Christie’s in London

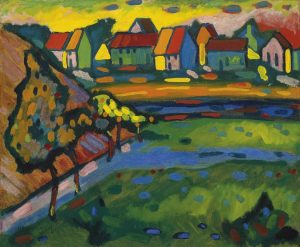

Works from this time — such as Murnau: Ansicht mit Burg, Kirche und Eisenbahn (1909), Murnau: Strasse (1908), and Herbstlandschaft mit Baum (1910) — mark a stunning advance. Bathed in high-key colour, they show the influence of Henri Matisse and the Fauves. Even more striking is the way Kandinsky simplified the forms of the local townscape and surrounding landscape, reducing them to basic shapes. This was a crucial period in his transition towards abstraction.

Wassily Kandinsky (1866-1944), Bayerisches Dorf mit Feld, 1908. 15 × 18⅛ in (38 × 46 cm). Sold for £4,969,250 on 21 June 2011 at Christie’s in London

Glimpses of a spiritual realm

Kandinsky wasn’t what we might call religious in the traditional sense, but he was deeply spiritual. Among the thinkers who most influenced him was Helena Petrova Blavatsky, co-founder of the Theosophical Society in 1875, who contended that there is a higher, immaterial realm beyond the visible world.

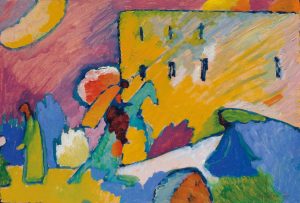

Wassily Kandinsky (1866-1944) ‘Strandszene’ 1909. 20¾ × 26⅜ in (52.8 × 67 cm). Sold for $17,189,000 on 6 May 2014 at Christie’s in New York

In the painting Strandszene, above, Kandinsky provided what appears to be a glimpse of that realm: a rich patch of red at the top of the canvas, beneath which human figures toil in the material world. In 1911 he penned a text, On the Spiritual in Art, in which he outlined art’s transcendental potential, suggesting that art should no longer depend upon discernible reality. His thinking in that treatise brought him one step closer to abstraction.

A first solo exhibition baffles critics

Alongside Münter, Franz Marc and a few others, Kandinsky briefly formed part of a group called ‘Der Blaue Reiter’ (The Blue Rider). This loose association of experimental painters exhibited together first in Munich, before exhibiting in Herwarth Walden’s Der Sturm gallery in Berlin. Walden was so taken by Kandinsky’s work that in 1912 he offered the artist his first solo show. It left the majority of critics bemused. Oskar Bie, of the Berliner Börsen-Courier newspaper, wrote that he couldn’t make ‘head nor tail’ of the semi-abstract objects and figures.

The perceptual phenomenon of synaesthesia

Kandinsky was a keen lover of music, and counted Richard Wagner among his favourite composers. He also saw a strong affinity between music and painting, believing in the perceptual phenomenon of synaesthesia — according to which the stimulation of one sense leads to the stimulation of another. (He duly thought that the colours and marks in a painting triggered particular sounds, just as the musical notes in a symphony triggered particular sights.)

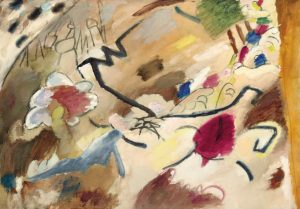

Wassily Kandinsky (1866-1944) ‘Studie für Improvisation’ 8, 1909. 38⅝ × 27½ in (98 × 70 cm). Sold for $23,042,500 on 7 November 2012 at Christie’s in New York

Kandinsky also gave music-inspired titles to three different categories of paintings: his ‘Compositions’, ‘Improvisations’ and ‘Impressions’ (studies for Improvisation 8, above, and Improvisation 3, below, were sold at Christie’s).

Wassily Kandinsky (1866-1944) ‘Studie zu Improvisation 3’ 1909. 17⅝ × 25½ in (44.7 × 64.7 cm). Sold for £13,501,875 on 18 June 2013 at Christie’s in London

Of composers who can be said to have influenced his art, one stands out: Alfred Schoenberg, the avant-garde Austrian, who set aside conventional rules of harmony in favour of a new, atonal approach. This was congruous with an art liberated from the obligation to represent external appearances.

A new kind of imagery

Kandinsky is hailed, alongside Piet Mondrian and Kasimir Malevich, as one of the fathers of abstract art, and in the years leading up to the First World War (considered for many the peak of Kandinsky’s career), he accelerated toward non-representational painting. In works such as Improvisation mit Pferden (Improvisation with Horses), below, colour is no longer contained by line, and Kandinsky essayed a new kind of imagery in which form took precedence over content.

Wassily Kandinsky (1866-1944) ‘Improvisation mit Pferden’ 1911. Oil on canvas. 28 × 39 in (71.1 × 99.1 cm). Sold for $12,687,500 on 13 November 2017 at Christie’s in New York

He realised he was placing new demands on his viewers, declaring that ‘an evolution in observance [was] necessary’. According to Professor Rose-Carol Washton Long, an authority on Kandinksy, this meant the spectator ‘taking part in the creation of the work almost as if taking part in a mystic ritual… Kandinsky forces [us] to decipher mysterious images’. In Improvisation mit Pferden, is the line of riders ascending into the top-right corner meant to suggest a journey towards spiritual awakening?

War forces a return to revolutionary Russia

When Germany declared war on Russia in 1914, Kandinsky became an enemy alien and was forced to return to his homeland. After the Bolshevik Revolution in 1917, he briefly — and enthusiastically — served as a commissar in the new regime’s Culture Ministry. He also participated in a number of group exhibitions. In time, however, as limits began to be placed on creative freedoms, Kandinsky (with his wife Nina, whom he’d married in 1917) decided to return to Germany.

The Bauhaus beckons

In 1921, at the age of 55, Kandinsky moved to Weimar to teach mural painting and introductory analytical drawing at the newly founded Bauhaus school. There he worked alongside the likes of Paul Klee, László Moholy-Nagy and Josef Albers. He had lost none of his messianic zeal, and believed fully in the Bauhaus philosophy of social improvement through art.

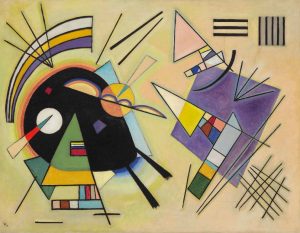

Wassily Kandinsky (1866-1944) ‘Oben und links’ painted in Weimar, March 1925. 27½ × 19⅝ in (69.9 × 49.8 cm). Sold for $8,311,500 on 15 May 2017 at Christie’s in New York

Oben und links, above, and Schwarz und Violett, below, were typical of his work from this period: still abstract but now marked by geometrical components such as grids, triangles and circles.

Wassily Kandinsky (1866-1944) ‘Schwarz und Violett’ April 1923. 30⅝ × 39½ in (77.8 × 100.4 cm). Sold for $12,597,000 on 5 November 2013 at Christie’s in New York

Order and balance of composition became key, consistent with Bauhaus thinking that art should be used in the service of better-designed buildings and objects for everyday use.

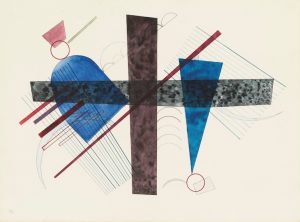

Wassily Kandinsky (1866-1944) ‘Blau in Rund und Spitz’ 1933. Watercolour on paper. 16½ × 22⅛ in (42.1 × 56.8 cm). Estimate: £80,000-120,000.

The Nazis label Kandinsky’s art ‘degenerate’

In 1933, not long after assuming power, the Nazi party closed the Bauhaus, prompting Kandinsky and his wife to move to the Paris suburb of Neuilly-sur-Seine. Initially they hoped the relocation would be for just a year or two, after which time they expected politics in Germany to have cooled. ‘We aren’t leaving for good,’ he wrote to his friend the art critic Will Grohmann, in 1934. ‘I couldn’t do that; my roots are too deep in German soil.’

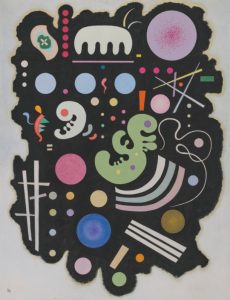

Wassily Kandinsky (1866-1944) ‘Noir bigarré’ 1935. Oil on canvas. 45¾ × 35 in (116.2 × 89 cm). Estimate: £8,000,000-12,000,000.

In 1937, however, Nazi authorities ordered the removal of 57 pieces by Kandinsky from the nation’s museums. Fourteen of these were included in the infamous Entartete Kunst (Degenerate Art) exhibition that opened in Munich that year — the show in which Hitler displayed the works of avant-garde artists he deemed to be ‘driving forces of corruption’. Kandinsky became a French citizen in 1939.

In a final flourish, he takes a bold new direction

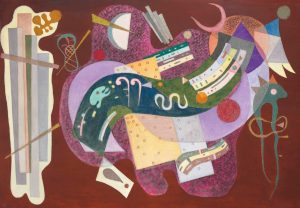

In France, Kandinsky’s art took a bold, new direction. In works such as Rigide et Courbé, below, he began to introduce more playful, non-geometrical, biomorphic shapes. These evoked the embryos, larvae, plankton and other minuscule life forms he’d observed while using a microscope — as well as ancient hieroglyphs and pictographs. All of these soared free across an open, unstructured ground.

Wassily Kandinsky (1866-1944) ‘Rigide et courbé’ executed in Paris, December 1935. 44⅞ × 63⅞ in (114 × 162.4 cm). Sold for $23,319,500 on 16 November 2016 at Christie’s in New York

The mood is consistently upbeat, belying the geopolitical upheavals at the time (German forces would enter and capture Paris in 1940). Kandinsky’s time in Paris was one of great productivity, yielding 144 oil paintings and around 250 watercolours and gouaches in just over a decade. He died in Neuilly-sur-Seine in 1944, at the age of 77.

Source: Christie’s