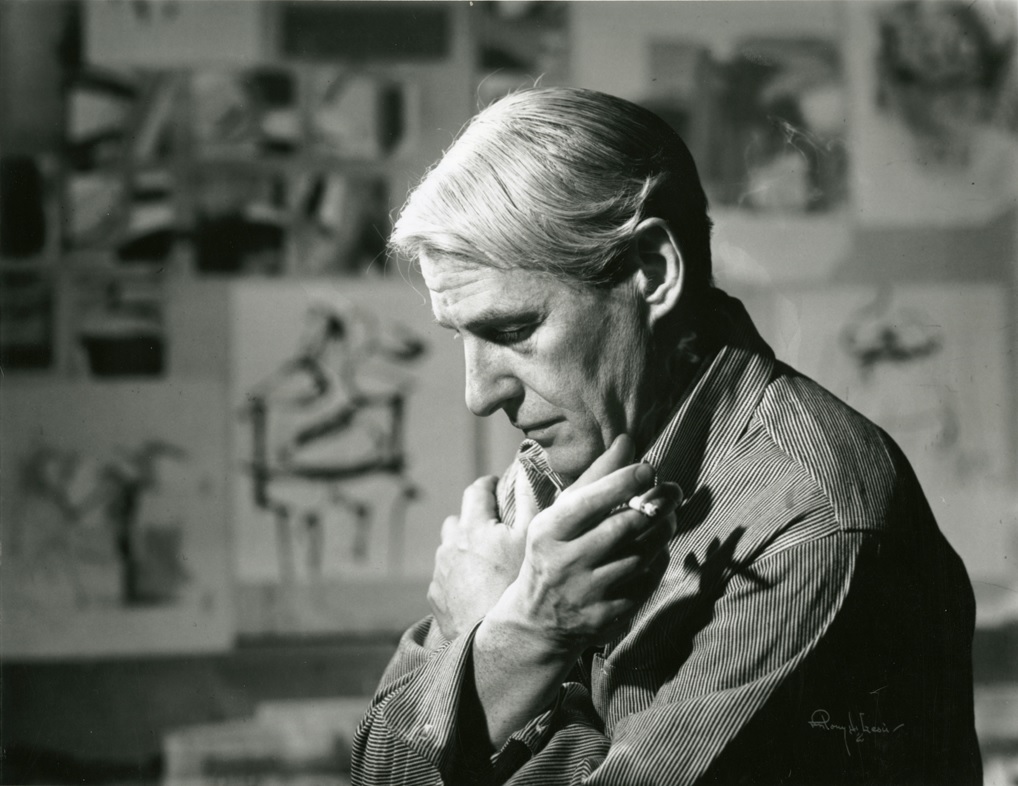

Willem de Kooning

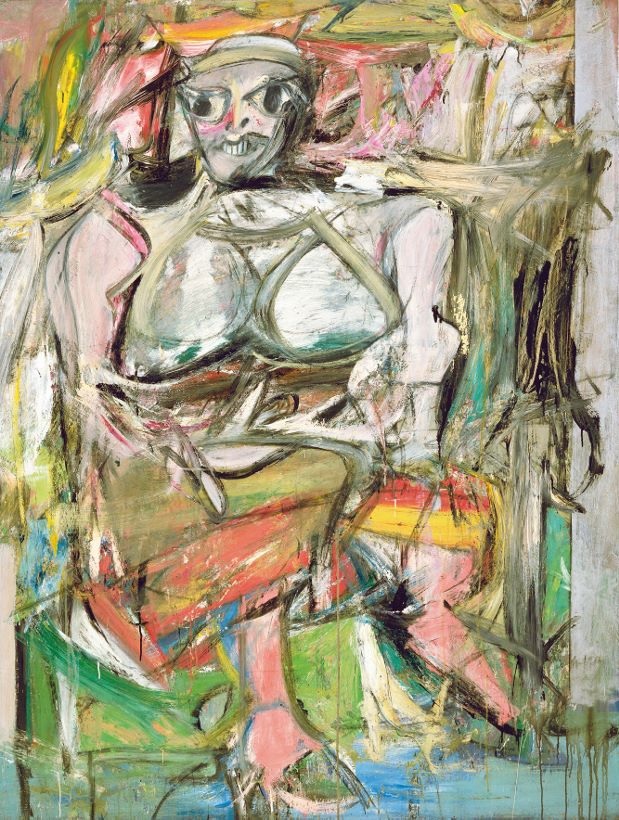

Willem de Kooning ‘Woman I’ (1950-52)

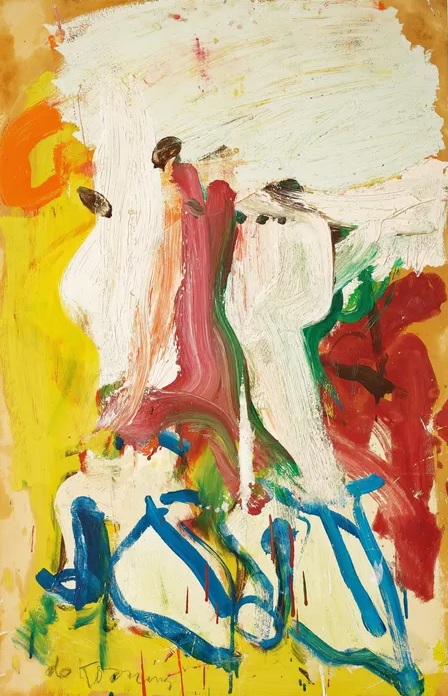

Willem de Kooning ‘Woman II’ 1952

Willem de Kooning detested conformity. While he became one of the most influential painters of Abstract Expressionism, he resisted association with the movement. Adhering to a single style—in particular, one that insisted on leaving representational imagery behind—was too limiting for the New York–based Dutch artist. Famously, he complicated pure abstraction by embedding figures within tempestuous slashes of paint and nebulous, biomorphic forms, as in his masterpiece Woman I (1950–52).

“Some painters, including myself, do not care what chair they are sitting on.…They do not want to ‘sit in style,’” he explained during a 1951 lecture, entitled “What Abstract Art Means to Me,” at the Museum of Modern Art. “Those artists do not want to conform,” he continued. “They only want to be inspired.”

Over the course of de Kooning’s seven-decade career, he gave numerous lectures and interviews that revealed the inspirations behind his shape-shifting, explosive compositions. Below, we highlight several lessons for artists that can be gleaned from his words. They explore the importance of dialogue, observation, iconoclasm, and even failure.

Lesson #1: Don’t be afraid to be influenced by fellow artists’ work

Willem de Kooning ‘Asheville’ 1948

When de Kooning was 21, in 1926, he moved from Holland to the U.S. to pursue a career in commercial art. But after landing in Manhattan, he met several artists who propelled him to focus on his personal practice. The early development of his work hinged on dialogue with his contemporaries, and he routinely noted his debt to fellow painters Arshile Gorky, Stuart Davis, and John Graham, in particular. “I was lucky when I came to this country to meet the three smartest guys on the scene,” he said in the biography Willem de Kooning, 1904–1997: Content as a Glimpse (2004) by Barbara Hess. “They knew I had my own eyes, but I wasn’t always looking in the right direction. I was certainly in need of a helping hand at times.”

De Kooning was never too proud to acknowledge the influence of his peers on his own work. He was especially impacted by Gorky, who he lovingly referred to as the “boss,” as curator Susan Lake has pointed out. “I am glad that it’s about impossible to get away from his powerful influence,” de Kooning wrote of his friend and peer, in a 1949 issue of ARTnews.

He emphasized the importance of more formal, organized exchanges between artists, too. In 1949, de Kooning and 17 other artists, including Gorky, Franz Kline, and Ad Reinhardt, founded The Club, a loft on East 8th Street where they gathered to talk aesthetics (and drink, too). Weekly Friday night conversations were dubbed “Subjects of the Artist” and later “Studio 35.” “It was so important, getting together, arguing, thinking,” de Kooning explained to Anne Parsons in a late-1960s interview.

The artist also made a point to see fellow artists’ work in exhibitions around New York. “You can safely say he saw everything,” his wife, the painter Elaine de Kooning, once told art historian Sally Yard. His interests weren’t just limited to the work of his peers, though; absorbing historical references also became integral to de Kooning’s process. “Picasso and Matisse showed us the way and we filled in with our own personalities,” he said in 1982. He openly drew from Rembrandt, Cézanne, Ingres, Mesopotamian idols, and Pompeian frescoes, too. “My paintings come more from other paintings,” he modestly told Harold Rosenberg in 1972. “This is my pleasure of living—of discovering what I enjoy in paintings.”

Lesson #2: Seek out glimpses of inspiration in the world around you

Willem de Kooning ‘The Privileged (Untitled XX)’ 1985

Unlike most of de Kooning’s Abstract Expressionist peers, observation of the world around him—as opposed to his inner life—provided the initial impulse for his paintings. He once referred to himself as a “slipping glimpser,” or a painter who drew from flashes of content he encountered in daily life. In a landmark 1960 interview with critic David Sylvester, he explained this: “Content, if you want to say, is a glimpse of something, an encounter, you know, like a flash—it’s very tiny, very tiny, content.” In other words, the bits of content that inspired elements of de Kooning’s canvases weren’t products of premeditated, planned observation, but rather a relaxed awareness of his surroundings.

Bits of color or random objects seen traversing Manhattan or Long Island, where he later lived, could inspire a painting or an entire series. “The artist associated the glimpse with the most ordinary kind of ‘happening’—somebody sitting on a chair, or a puddle of water reflecting light,” wrote art historian Richard Shiff. A mouth he glimpsed in a magazine inspired the focal point of the “Woman” series: her wide, toothy smile. “If I really think about it,” de Kooning explained to Sylvester of these shards of content, “it will come out in the painting.”

But de Kooning wasn’t as interested in the formal qualities of these glimpses as much as their psychological hold on him. He sought to paint “the emotion of a concrete experience,” as he told Sylvester, rather than the object or encounter itself.

Lesson #3: Pay attention to your desires, not the critics

Willem de Kooning ‘Marilyn Monroe’ 1954

Willem de Kooning ‘East Hampton XVII’ 1968

De Kooning’s eclectic, experimental approach to painting wasn’t always admired by his peers. “No single image represents his style or characterizes his career as do, for example, the poured paintings of Jackson Pollock and the abstracted topographies of Clyfford Still,” Lake explained in Willem de Kooning: The Artist’s Materials (2010).

He boldly blended styles—figuration and abstraction, most notably—a practice that was anathema to the era’s traditional and progressive critics. “Conservative critics complained about the artist’s attempt to mix painterly abstraction and expressionist figuration,” while “champions of ‘advanced’ art attacked de Kooning for his conservative return to figure painting,” Lake continued.

But the painter remained staunchly committed to hybridization. “Even abstract shapes must have a likeness,” he once said.

Several times, de Kooning refused to become an official member of American Abstract Artists, an organization that would have restricted his use of figuration. In a statement accompanying his black-and-white canvas Painting (1948), an abstract composition incorporating elements of figurative drawings, he conveyed his disdain for blindly following a single style or movement: “I’m not interested in ‘abstracting’ or taking things out or reducing painting to design, form, line, and color,” he wrote. “I paint this way because I can keep putting more and more things in—drama, anger, pain, love, a figure, a horse, my ideas about space.”

In 1960, Sylvester asked de Kooning about the reaction he received, upon embedding recognizable imagery into abstraction. The painter responded bluntly and resolutely: “They attacked me for that, certain artists and critics. But I felt this was their problem, not mine.…I fear that I’ll have to follow my desires.”

Lesson #4: Embrace imperfection—even failure

Thomas Hoepker ‘Willem De Kooning in his East Hampton studio’ 1997

De Kooning didn’t shy away from failure. In fact, he believed “that serious art was doomed to fall short of its potential,” as art historian Robert Storr has explained. Perhaps surprisingly, the concept motivated de Kooning’s work. “Failure ought to take your whole life, active life,” the painter once said. Often, he would rework canvases over and over again, letting mistakes guide his next composition.

De Kooning explained that accepting failure and imperfection unburdened him, and opened him up to new modes of experimentation. “I get freer.…I have this sort of feeling that I am all there now,” he explained in “What Abstract Art Means to Me.” “It’s not even thinking in terms of one’s limitations, because they have to come naturally. I think whatever you have you can do wonders with it, if you accept it.”

Even into his seventies and eighties, de Kooning continued to experiment. His paintings become looser, more pared down, and buoyant. Storr ascribes this shift, in part, to his fearlessness and his willingness to fail. “Failure would have confirmed the opinion of those who had been impatiently awaiting definitive proof of his decline,” Storr wrote. “But de Kooning had never been afraid of failure.”

“I never was interested, you know, how to make a good painting,” the artist told Sylvester as early as 1960. “I didn’t want to pin it down at all.” In other words, embracing imperfection freed de Kooning, and led him to make some of art history’s most daring and influential canvases.

Source: Artsy