It is the quirk of inspiration that a simple postcard can open up an entire world. Born in Beijing one hundred years ago in 1920, Zao Wou-Ki spent much of his childhood in Jiansu. His father was a banker and art collector who cultivated in his son a strong interest and understanding of art from a young age. During this time Zao’s uncle returned from his latest travels to Paris and brought his nephew a postcard of the painting The Angelus by Jean-François Millet. This was a profound moment that opened a window on Western art for young Zao Wou-Ki.

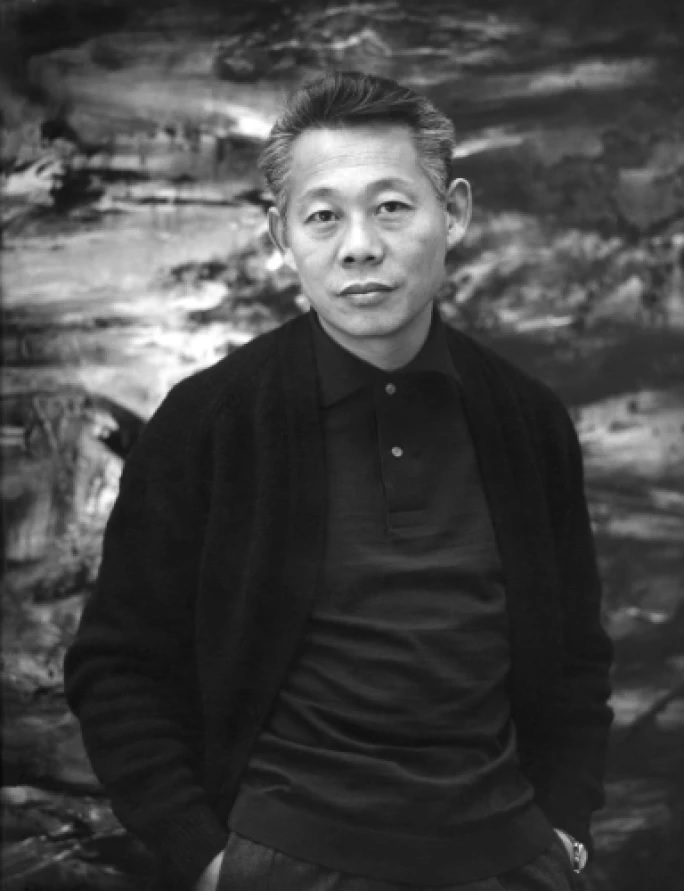

Zao Wou-Ki, 1966. Photograph: Pitz (© All rights reserved)

Zao Wou-Ki’s travels took him across the world. He moved to Paris in 1948, and in the first decade there, he embarked on two extended trips – the first to Italy and Spain in 1951 to 1952, and the second to North America beginning September 1957. He visited his brother Wu-wei in New York, a centre of post-war avant-garde art and culture. During his four months in New York, Zao first encountered Abstract Expressionist painters such as Franz Kline, Philip Guston, Mark Rothko, and others. This inspired him to develop a bolder style – one that integrated American action painting with the mesmerizing lyrical nature of the Chinese calligraphy.

At the introduction of Pierre Soulages, Zao Wou-ki met Samuel Kootz, who had founded Kootz Gallery in New York in 1945. With his foresight and vision, he discovered and supported many emerging post-war artists. Kootz’s gallery on Madison Avenue became a symbol of the American art world, and through Kootz, Zao learned more about American Abstract Expressionism, which would significantly elevate his style.

Zao Wou-Ki, 15.02.65

Following his stay in New York, which proved pivotal to Zao Wou-Ki’s career, he then went on to Chicago and San Francisco. Accompanied by Pierre Soulages and the French artist’s wife, Zao then traveled to Hawaii, Japan, and finally Hong Kong in 1958.

In 1958, Zao Wou-Ki met the Bokujin-kai, a group led by Kyoto-based calligraphers Morita Shiryu and Inoue Yuichi. By the time of Zao’s meeting with Morita and Inoue, the Bokujin-kai had already established a dynamic dialogue with the American Abstract Expressionists through the art and literary journal Bokubi. Notably in its no.76 issue on May 1958, Bokubi included Zao’s view on calligraphy which gets to the heart of the artist’s work.

“Each character has its respective meaning for me, ultimately I think of characters as denoting natural things. For me, I think that characters are one kind of gates. In other words, they become a spot that allows passage between the outside world and my own inner world, so they are a gate, they are a door. I also think of them as something that forms the basis for artistic practice.” — ZAO WOU-KI, ‘BOKUBI’ ISSUE NO.76 , MAY 1958

All that Zao Wou-Ki experienced during his yearlong voyage propelled the ultimate evolution of his Oracle Bone Period which he had already started four years earlier. In 1954, Zao began his explorations of ancient Chinese characters in oil painting, and as he deepened his understanding of the connections between calligraphic expression and the artist’s internal and external states, Zao’s works in the latter years of his Oracle Bone Period (1954-1959) became far more expressionistic, characterized by free and spirited brushstrokes on large canvases. This paved the way to his Hurricane Period, which began in 1959.

Zao Wou-Ki, 04.01.62

From 1958 to 1965, Zao made annual trips to New York for exhibitions.

He experienced the American cultural context as entirely different from the long histories of China and France. Inspired by the unrestrained, bold, and innovative spirit of American culture, he approached a new way in his painting style. In his autobiography, Zao wrote that, at this time, ‘I began to paint freely and do what I wanted… I wanted to depict movement, whether lingering in one place or flying fast as lightning. The multiple resonances of contrasting and identical colours made the canvas vibrate, allowing me to find a central, glowing point.’ This change in 1959 inspired the beginning of the Hurricane Period, recognized as one of his creative peaks.

Zao Wou-Ki. Mon pays.

By this time, his works were shown in many other cities in the U.S., including San Francisco, Sarasota, and Cambridge. During this time, Zao’s paintings had been well received by the competitive New York art scene, both academically and commercially. The Kootz Gallery held a show for Zao every two years from 1960 to 1966, which laid a foundation for the artist in the American and international art worlds and encouraged more museums and private collectors to purchase his work. This wonderful collaboration reflects Kootz’s affirmation of Zao Wou-ki as an artist with an international profile and highlights Zao’s success as a Chinese artist in the global art world in the 1950s and 1960s.

Zao Wou-ki stayed in the United States for less than two years, but Kootz’s influence on him lasted well beyond this brief time. In his autobiography, Zao mentioned that Kootz was ‘accustomed to large-format paintings by American artists.’ With Kootz’s encouragement and guidance, Zao started to use no. 120 canvases measuring nearly two metres in 1959. Unlike in his Oracle Bone Period, his large-format Hurricane works required him to throw himself—body and soul—into the paintings. He could not have created these paintings without this international experience and prime physical condition. 15.02.65 is a classic work from this creative peak in Zao’s career.

Zao Wou-Ki. Les Oliviers.

Zao Wou-Ki. Sans titre.

Swift, surging, and scribbled ink lines rush into the painting from the left and right, converging and colliding in the centre. Bright yellow tones, like a golden light, illuminate a work exploding with energy. From the wild brushwork in 15.02.65, the viewer can envision Zao Wou-Ki in the prime of his life standing in front of this massive no. 120 canvas with brush in hand, poised to begin wrestling with the painting. This piece is typical of the works that Zao Wou-Ki made during his collaboration with New York’s Kootz Gallery in the 1960s; it was also the most important painting in his 1965 solo show at the gallery. Kootz Gallery seldom published catalogues, but they chose this work as the focal point for this exhibition’s promotional materials and printed a catalogue, which shows how much Samuel Kootz appreciated the artist and his work, as well as his importance in the international art world.

“Zao Wou-Ki’s artistic fate is not merely that of the individual. It is intimately tethered to the many thousand years of evolution of Chinese painting … In reality, when talking about what has been gained from his works, it can be said that one hundred years of anticipation in Chinese painting can now be put to rest. The symbiosis between East and West that should have occurred long ago has finally appeared for the first time.” — FRANÇOIS CHENG, LITERARY CRITIC

Source: Sotheby’s